Over time I’ve written a number of posts about specific dishes and types of food highly associated with restaurants, some of them rarely prepared in home kitchens. Other items listed below are not restaurant dishes, but items that restaurants need to provide on the table or use in the kitchen – and that have played special roles — such as butter, cheese, bread, sugar, parsley, water, and cooking oil.

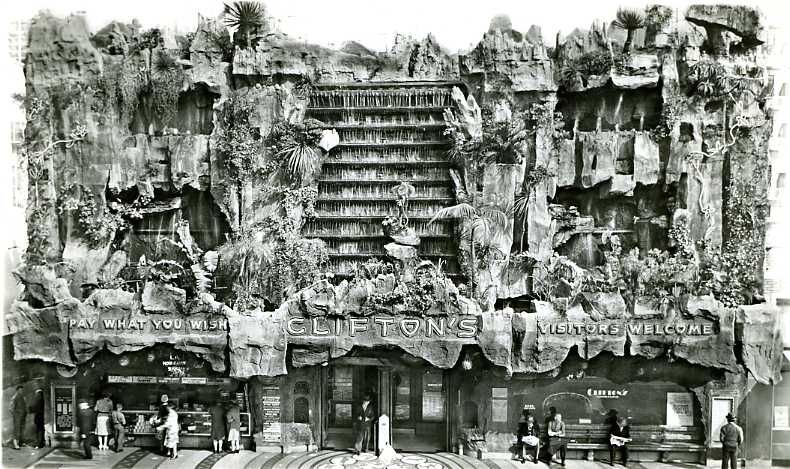

Beans – Beans were a basic dish in cheap eateries in the 19rh and early 20th centuries and furnished a meal for any time of day or night. Writers were attracted to beaneries for their symbolic association with rock-bottom reality. Beaneries disappeared when the increasing wealth of post-WWII America led restaurants to shun beans except in chili.

Bread – Clearly the filler-upper in America’s early eating places, it accompanied even the cheapest meals. In more modern times, it has served as a consolation to hungry diners waiting for their orders to arrive at the table. Today as many restaurants “monetize” their bread baskets, it is no longer “free.”

Butter – It has appeared on restaurant tables in various guises — whipped, as rosettes, curls, or pats. It was a bit of headache for restaurants but they had to serve it as long as they served bread. Restaurants continued to serve it during WWII when the federal government backed down on reducing the amount they were allowed.

Cheese – Although the custom of finishing a meal with a cheese course never really caught on in American restaurants, their use of cheese in a variety of menu items continued to rise throughout the last century. Its ever-increasing popularity was boosted by Italian dishes, saloon “free lunches,” cheeseburgers, and of course the rise of pizza and Mexican fast food chains. [pictured: chili cheese fries]

Chocolate desserts – Not much chocolate on the menus of hotels and eateries in the 19th century, but that was going to change. No doubt the entry of women into the dining-out public in the 20th century had a lot to do with its rising popularity, especially in the form of baked goods. By the 1970s a huge number of Americans began to declare themselves “chocoholics.”

Club sandwiches – Perhaps they originated in clubs, but that mere suggestion gave them a cachet and no doubt helped spread their popularity. That and how neatly they were layered and cut into four dainty triangular pieces recommended them to diners who were upwardly mobile – or wished they were. Perfect for restaurants because, really, who wanted to go to all the extra trouble to construct one at home.

Coffee – Coffee, the beverage of sobriety and business, was basic to restaurants for most of the 19th and much of the 20th century. And, surprisingly, its price per cup stayed at 5 cents in many restaurants until the 1940s. By the 1970s it was up to 25 cents but it was increasingly losing out to soft drinks. Eventually it lost its major place as an accompaniment to meals, except maybe with desserts.

Cooking oil – If anything shouts restaurant fare, it is the long history of deep-fried food served in public eating places. Early fryers relied on lard, later replaced with cheaper cottonseed oil. The number of items that are fried has only increased over the decades, to include meats, fish, potatoes, a wide assortment of vegetables, even cheese.

Crepes – Restaurants specializing in crepes became popular in the 1960s and 1970s, fueled by increased travel abroad and interest in wider food horizons. Yet, unlike other foods regarded as rather exotic, crepes were affordable. The Magic Pan chain became popular and was acquired by a major food corporation. But by the mid 1980s the trend had expired and the delicate food was declared out of fashion.

Eggs Benedict – A truly “legendary” menu item in the sense that its origin story was concocted to give it enough glamour that a higher price could be charged. Maybe not quite that deliberate, but close. A legend appears to have been invented, or perhaps embroidered, in the 1940s. Eventually the dish, a brunch favorite, became popular enough that it could stand on its own.

Fortune cookies – The cookies probably made their initial appearance in the 1910s at Golden Gate Park’s Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco. It didn’t take long before they were regarded as an invariable component of a Chinese restaurant meal. In the 1960s the paper on which fortunes are printed was sterilized and the message was printed with non-toxic vegetable dyes.

French fries – In cooking terms, frenched does not refer to France but to cutting food into strips. In France our “French fries” are their “frites.” The cost of cooking oil hampered their adoption in restaurants here for a time, but they began to appear on more menus in the early 20th century, especially after demand rose as WWI veterans who had been introduced to them in France returned home.

Fried chicken – Fried chicken could not become popular, inexpensive – and profitable — restaurant fare throughout the country until chickens went into mass production, mainly after the second World War. Before that fried chicken lovers had to travel into rural areas, often to tea rooms, to find it on a menu.

Hamburgers – Perhaps because in the 1890s hamburger sandwiches were strongly associated with “smelly” night lunch wagons whose customers ate them standing on the street, hamburgers were disdained by those of higher means. It didn’t help that in some cases the ground meat was questionable in quality and had been dosed with preservatives. It may have been young people who changed the equation, boosting hamburgers’ popularity in the 1920s.

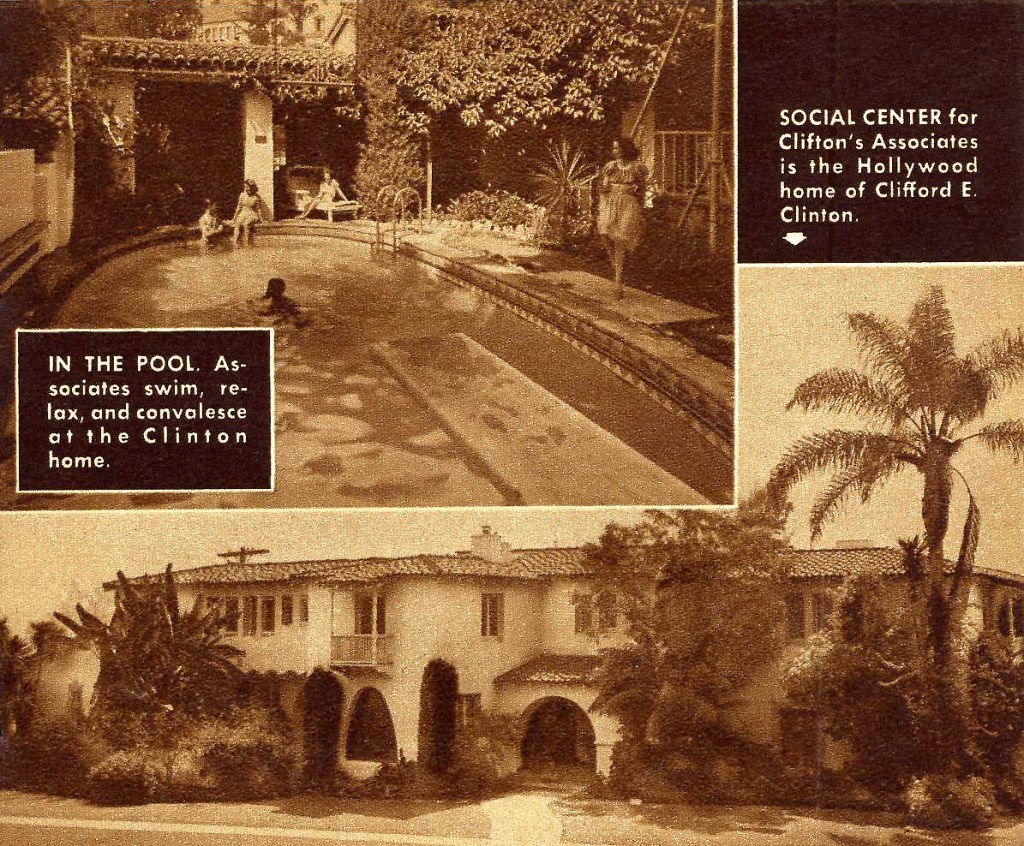

Meat and potatoes – The popularity of restaurant meals containing both components was intense in the 19th and 20th centuries. The mutton of the 19th century vanished but the love of beef seemed eternal. This was the bedrock American diet, especially popular with men who patronized steak houses. It was not challenged until the 1970s, mostly for health reasons, and yet did not disappear.

Onion rings – Once Americans got over their aversion to onions — mostly in the 1970s when fast food outlets began to offer them — they decided they really loved those deep fried treats! It helped a lot that they had become available frozen and breaded, relieving kitchen workers from having to handle the smelly vegetables.

Pancakes and waffles – Pancakes had long been short order staples, growing in popularity in the Depression as an inexpensive, yet filling, menu choice. Later, the proliferation of chains specializing in pancakes made them popular for all meals, not just breakfast, and attracted the family trade. Waffles have probably been less popular than pancakes overall, but in some ways they proved more versatile since they could serve as a base for other foods, especially fried chicken.

Parsley – Some people eat it, but its main role in restaurants has been decorative. Better yet, it has filled in empty spaces on plates. Its use as a garnish departed from the European practice of matching garnishes with foods whose taste and texture they enhanced. In this country, parsley could appear on any plate regardless of what was being served. Nevertheless, its mere presence signals to the diner that s/he is eating away from home.

Pizza – In its early years it was known mainly to Italian-Americans, but it came into the mainstream in the 1950s, though still relatively unknown in some areas of the country such as the South. For a time it was regarded as a snack more than as a meal. Partly due to the growth of nationwide chains, it would eventually surpass hamburgers in popularity. Cities vie for pizza fame, among them New Haven CT, home of apizza.

Salad – Salads tended to be reserved for elites in the 19th century, but in the 1910s they reached a wider slice of Americans in small French and Italian cafes. As the century progressed salad moved into the mainstream, popularized by salad bars. Meanwhile Caesar salads migrated northward from Mexico into California, while some other parts of the country enjoyed the unfortunately named “wop” salads.

Shrimp – Although hotels included shrimp salad on their menus in the later 19th century, the little crustaceans didn’t achieve notable attention until the rise of shrimp cocktails in the 20th century. Next came breaded deep-fried shrimp, their use boosted by frozen products marketed to restaurants.

Spaghetti – The early non-Italian fans of Italian restaurants featuring spaghetti dinners were drawn by their semi-forbidden attractions, namely red wine and garlic, plus the fun of wrangling spaghetti. In other words, precisely those things that made upright Americans uncomfortable. Artists and musicians, considered “bohemians,” boosted its popularity.

Sugar – Largely absent on restaurant tables today, sugar was once demanded by restaurant customers. Over time the unsanitary sugar bowl, often shared with strangers, was replaced with shakers and then individual paper packets. Wartime restrictions posed a vexing issue for proprietors, as did the behavior of some customers who employed ingenious methods to make off with the scarce commodity.

Surf ‘n’ turf – Brought to this country via airplane in the 1930s, South African “rock lobster” introduced a new menu selection that was destined to achieve fame. The inexpensive lobster tails paired with steak became popular in the 1960s, remaining a favorite into the 1970s. Price increases by the late 1970s were no doubt responsible for the once-inexpensive combo’s decline.

Tomato juice – Introduced to restaurants in the 20th century, tomato juice was once a trendy drink that could serve as an appetizer. Unsurprisingly, its menu appellation, Tomato Juice Cocktail, reflected its popularity during Prohibition. It was sometimes presented in special concoctions – with cottage cheese stirred in, or perhaps orange or clam juice.

Water – It seems that diners were first served a glass of water with their meal in the 1840s when some large cities, including Boston and New York, acquired reservoirs. The new custom pleased temperance advocates, but some newcomers, Italians for instance, preferred wine with their meals. Though many Americans don’t drink the water provided in restaurants, they tend to want it poured for them anyway.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.