In their restaurant career sandwiches came from humble beginnings. They could sometimes be found in eating places as far back as the early 1800s, such as at the Ring of Bells, a porter and oyster house in New York. But they became more popular when they teamed up with beer joints after the Civil War. They also flourished in Boston’s “sandwich depots” of the 1880s — bean sandwiches included. And they were among the edibles offered by lunch wagons, saloons, and stand-up buffets in the late 19th century.

But it was the trend toward lighter mid-day meals in the early decades of the 20th century, spurred by the growth of cities, that gave sandwiches their big boost. Then, as light meals replaced hot dinners at noon, they found their niche, furnishing a quickly prepared menu item available in a variety of styles and combinations. Sandwiches of all kinds – named after celebrities, toasted, clubs, St. Paul’s — continued to flourish until after WWII when hamburgers began to take center stage.

While some eating places stuck with hot meals at noon in the early 20th century, others were quick to embrace sandwiches, particularly lunch rooms, tea rooms, drug stores, and delis. The sandwich shop was declared the winner among fast food restaurants. To critics the proliferation of this slapped-together fare was a sign of cultural decline. “The postwar decade might be known as the era of the sandwich,” declared cultural observer Eunice Fuller Barnard in a New York Times article of 1929 with the mournful headline, “We Eat Still, But No Longer Do We Dine.”

Among new developments was the formation of sandwich chains such as the Tasty Toasty and the Hasty Tasty. The B/G System was one of many in that category, which also included R&C, C&L, S&S, and no doubt other alphabetical combos across the USA. In 1924, the “Purely American, Meal in a Minute, No Tipping” B/G chain claimed to pay wages allowing their workers to “live according to American standards.” It had outlets in 16 large cities and was about to spread further. Was St. Louis the champion host of sandwich shops? Included among the city’s 52 sandwich shops in 1938, there were at least 6 “sandwich systems,” the Continental, Hollywood, Nickel Plate, Night Hawk, Ure-Way, and Yankee.

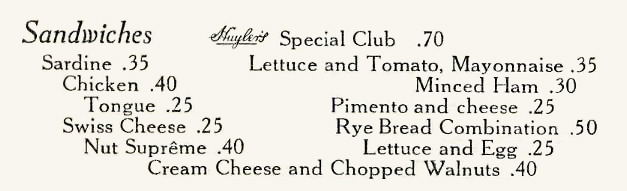

The sandwich selections on the menu shown here are from the Huyler’s confectionery-based chain. Tongue and Cream Cheese sandwiches, rarely (ever?) seen today, were quite popular in those early years (1921 menu above).

Polly’s Cheerio Tea Room’s Ham and Jam on French Toast would seem to be unusual, though perhaps Los Angelenos would have disagreed (1932 menu above).

I can’t account for why Schrafft’s in New York City felt the need to indicate which sandwiches were made with mayonnaise (1938 menu above). I’ve found one other tea room, located in St. Joseph MO, that included the same annotations.

Among the other interesting sandwich combinations I’ve found are Cucumber & Radish (25c at The Cortile in NYC in 1928); Egg and Green Pepper with Mayonnaise on Whole Wheat Gluten Bread (25c at Schrafft’s in 1929); “Chef’s Pride,” Smoked Tongue, Sliced Chicken, and Deviled Eggs double decker (50c at Townsends, San Francisco in1933); Peanut Salad (10c at The Candy Box in Winona MN in 1935); Peanut Butter, Sliced Tomato, Bacon, and Lettuce triple decker on toast (25c at The Little White House in NYC in 1936); and Marshmallow and Peanut Butter (15c at The Bookshop Tearoom in Springfield MA in 1946).

I prefer my BLTs without peanut butter. Hold the marshmallows, please.

© Jan Whitaker, 2021

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.