During the Civil War, fairs were held in over twenty Northern cities to raise funds for the United States Sanitary Commission, a private organization that supplemented the Union Army Medical Corps’ efforts to care for wounded soldiers.

New York state held five fairs, in Albany, Poughkeepsie, Rochester, Brooklyn, and New York City. The Brooklyn and New York City “Sanitary Fairs” were massive endeavors resulting in donations of enormous amounts — $300,000 and $1,000,000, respectively — to the Sanitary Commission.

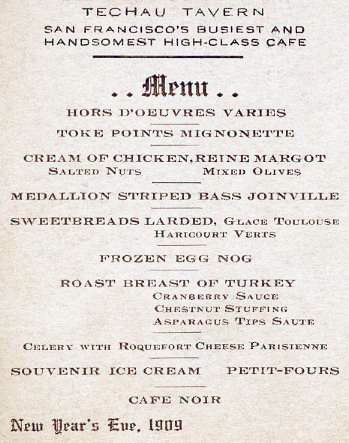

The fairs featured music, displays of art and curiosities, tableaux vivants, and other entertainments. Restaurants were an especially popular attraction. This week, a friend whose ancestors were involved with the Brooklyn fair gave me a wonderful printed-in-gold bill of fare from that fair’s Knickerbocker Hall Restaurant.

The fairs featured music, displays of art and curiosities, tableaux vivants, and other entertainments. Restaurants were an especially popular attraction. This week, a friend whose ancestors were involved with the Brooklyn fair gave me a wonderful printed-in-gold bill of fare from that fair’s Knickerbocker Hall Restaurant.

There were two main eating places at the two-week-long Brooklyn & Long Island fair, the larger one located in the temporary, specially built two-story Knickerbocker Hall located next to the Brooklyn Academy of Music [shown above]. The other restaurant, The New England Kitchen, occupied another temporary building across the street [shown below].

The Refreshment Committee in charge of the two restaurants was quite successful in getting donations of food supplies, including almost $20,000 worth of wine. But public opinion nixed serving wine, along with holding raffles, as improper for a fair in the “City of Churches.” So the wine was given instead to the New York Metropolitan Sanitary Fair which was held about a month after Brooklyn’s, in April of 1864.

The Refreshment Committee in charge of the two restaurants was quite successful in getting donations of food supplies, including almost $20,000 worth of wine. But public opinion nixed serving wine, along with holding raffles, as improper for a fair in the “City of Churches.” So the wine was given instead to the New York Metropolitan Sanitary Fair which was held about a month after Brooklyn’s, in April of 1864.

Despite the absence of wine, the Brooklyn fair outdid the Metropolitan NYC fair in how much money its  eating places cleared. Compared to the Metropolitan NYC fair, the Brooklyn menu was simplified, with no relishes or fruit, and few soups, cold dishes, or pastries. Brooklyn netted $24,000 for the cause, while the Metropolitan fair cleared only a little over $7,000 because, unlike Brooklyn, they received little donated food (uh, what happened to the wine?). Brooklyn’s New England Kitchen added perhaps as much as another $10,000 for the Sanitary Commission.

eating places cleared. Compared to the Metropolitan NYC fair, the Brooklyn menu was simplified, with no relishes or fruit, and few soups, cold dishes, or pastries. Brooklyn netted $24,000 for the cause, while the Metropolitan fair cleared only a little over $7,000 because, unlike Brooklyn, they received little donated food (uh, what happened to the wine?). Brooklyn’s New England Kitchen added perhaps as much as another $10,000 for the Sanitary Commission.

Brooklyn’s Knickerbocker Hall Restaurant, which could seat 500 at a time and took in about $2,000 a day, was under the direction of the men’s refreshment committee, while the New England Kitchen was run by a committee of women. The Kitchen was tremendously popular, serving 800 to 1,000 persons daily. But it occupied too small a space and, as the commemorative volume issued by the fair noted, would have made a greater profit had it been able to accommodate larger crowds.

Brooklyn’s Knickerbocker Hall Restaurant, which could seat 500 at a time and took in about $2,000 a day, was under the direction of the men’s refreshment committee, while the New England Kitchen was run by a committee of women. The Kitchen was tremendously popular, serving 800 to 1,000 persons daily. But it occupied too small a space and, as the commemorative volume issued by the fair noted, would have made a greater profit had it been able to accommodate larger crowds.

Unlike the Knickerbocker, the Kitchen’s bill of fare did not replicate that of a fine restaurant. Nor did the Kitchen follow the prevailing custom of hiring Afro-American men as waiters. The Kitchen used (white) women volunteers who served meals dressed in mid-18th-century costumes that visitors found ugly yet fascinating. For a set price of 50 cents, considerably less than a typical dinner composed from the Knickerbocker Hall’s a la carte menu, they served a down-home meal of such things as pork & beans, brown bread, applesauce, baked potatoes in their jackets, hasty pudding, and cider. Food was eaten from old china with a two-tined fork. The Kitchen also hosted events such as spinning wheel demos, apple paring bees, and an actual wedding.

Though it’s hard to draw a straight line from The New England Kitchen to women’s tea rooms of the early 20th century, it is notable how many tea rooms adopted a similar theme, right down to the old-style cooking fireplace and spinning wheel. It was also significant that so many women assumed executive and managerial positions on fair committees, especially in the New England Kitchen, and it’s probable that many of them remained active in public life after it ended.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

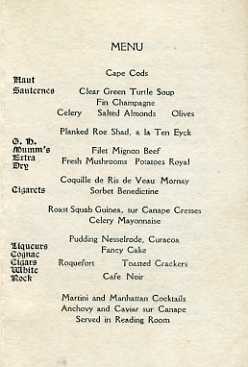

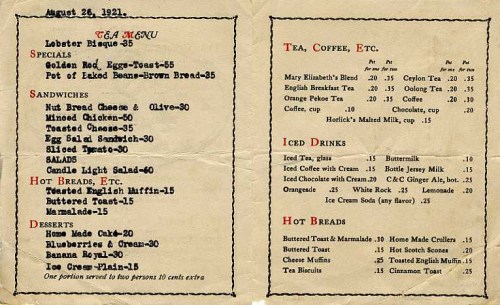

I always find it difficult to judge menus from the 19th century because our eating habits, food preferences, and food resources have changed considerably since then. It is difficult to decide whether any given menu is fine, average, or poor. The following menu was designed by a hotel steward (stewards were in charge of expenses) for a banquet in 1893. Almost certainly wines would have been served with the seven courses (which are Soup, Fish, Roast, Punch, Entree, Dessert, and Coffee).

I always find it difficult to judge menus from the 19th century because our eating habits, food preferences, and food resources have changed considerably since then. It is difficult to decide whether any given menu is fine, average, or poor. The following menu was designed by a hotel steward (stewards were in charge of expenses) for a banquet in 1893. Almost certainly wines would have been served with the seven courses (which are Soup, Fish, Roast, Punch, Entree, Dessert, and Coffee).

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.