Through the years a number of writers have described deceptive practices and foul scenes in restaurant kitchens where they have worked. Probably the best known authors are George Orwell (Down and Out in London and Paris, 1933) and Anthony Bourdain (Kitchen Confidential, 2000).

In those books, and in periodicals, I’ve read many reports of bad restaurant food, along with dishes misrepresented on menus. But I’m still a bit stunned after reading Restaurant Reality: A Manager’s Guide by Michael M. Lefever (1989). One of the biggest surprises is that he reveals his own willing involvement in kitchen tricks and horrors inflicted on guests — even in restaurants he and his wife owned and operated.

The book has a puzzling disclaimer on the copyright page: “This book is a composite of the author’s own experiences. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or locales is purely coincidental.” But, whether absolutely factual or not, and despite being aimed at college students interested in restaurant management, the book seems to sanction questionable activities.

In his preface to Restaurant Reality the author makes several statements that seem to undermine the disclaimer somewhat. He says that he tried to present “an authentic overview” that was “a real eye-opener for anyone who has ever eaten in a restaurant.” He adds that while the content may be shocking, “that’s how things really are.”

Starting at age 14, Lefever had at least a 23-year career in a number of restaurant roles, including dishwasher, server, cook, and bartender for an Italian restaurant, followed by unit manager and district manager for a fast-food chain, and regional manager for a dinner-house chain. Plus, in between the chains, he and his wife were owner-operators of three independent restaurants. Following his restaurant career, he held academic positions both as Associate Dean of the Conrad Hilton College of Hotel and Restaurant Management at the University of Houston and as head of the Department of Hotel, Restaurant and Travel Administration at UMass Amherst.

Although no names of individuals, places, or restaurants are given in the book, I have discovered that the third restaurant the Lefevers owned briefly was The Balcony in Folsom, CA. According to a 1983 story in the town’s paper, their two previous restaurants were in Bend OR and Salt Lake City, probably in that order.

How things really were

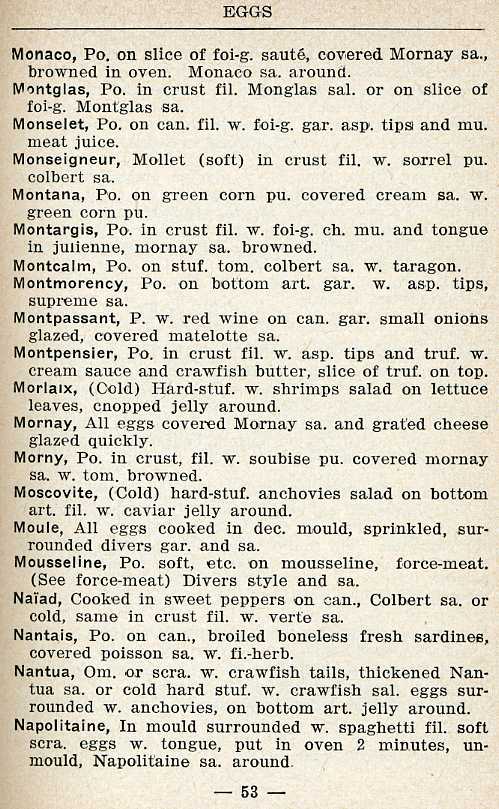

At age 16 Lefever became head cook at an Italian restaurant. It was before microwave ovens were common so hot water was used for parboiling and defrosting items such as lobster tails. The same water might be used for multiple items, such as pasta, chicken, and fish, as well as frozen steaks before they went on the broiler. He remarks, “This may be of some interest to readers who are strict vegetarians.”

No matter what the customer ordered at the Italian restaurant, all steaks were delivered to guests rare and cooked further only if they complained. If the customer insisted on a well-done steak the kitchen took revenge by putting it in a deep-fat fryer, followed by treatment with a blowtorch which caused it to burst into flames. Just before it burned to a crisp they would throw it on the floor and smother it in salt, then shake off the salt, put it on a platter and brush it lavishly with butter. He claims – and maybe it was true – that customers loved these steaks and some started asking for theirs charred.

As a fast-food unit manager, he oversaw (or witnessed? or heard about?) some truly disgusting practices. For instance, afternoon employees hired mainly to clean toilets and dispose of trash often did some off-hour cooking as well — but they weren’t always terribly sanitary. If no fresh lettuce was available, he writes, “the afternoon employee might fish out of the garbage can some discarded outer leaves.” They were oversized with tough spines, so the worker would “simply place his palm on the assembled sandwich and smash it downward.” When condiments squished out, he would “take a dirty cleaning rag” and wipe off the bun.

Since Lefever’s monthly bonus was based on keeping costs down, he recycled sandwiches that had officially expired as often as he could, even though this subverted the chain’s system. Eventually they began to look inedible. Then the workers would replace limp lettuce, spray the dry bun with water, and make other repairs. If that didn’t work they would disassemble the sandwiches and salvage the valuable parts for remakes during the off-hours, and so much the better if the customers were nighttime drive-thrus who had spent their evenings in a bar.

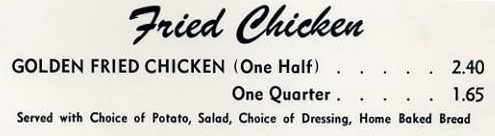

At the Lefevers’ own restaurant, The Balcony, servers were instructed to tell customers that all dishes — Veal Piccata, Beef Wellington, and so on — were prepared on site though they actually came from a supplier of frozen entrees. The cooks were highschool students who defrosted them in a microwave while doing their homework.

He declares that customers who found eggshells in their omelets should have been grateful since this meant the restaurant used fresh eggs rather than processed omelet mixes. But it could also mean that they came from the bottom of containers they used to store hundreds of cracked eggs in water. And, he reveals, “The bottom also collected the heavier eggs, which result when hens are sick, given a strange diet, or frightened.” Customers requesting decaffeinated coffee didn’t necessarily get it, since servers randomly grabbed the handiest pot, switching the red or green plastic bands that indicated type of coffee.

In discussing food spilled on the floor, he writes, “I have served . . . entrees spilled and then salvaged such as lasagne, beef stew, chili, pasta, and scrambled eggs. Steaks and chops are no problem at all. Simply put them back on the grill or in the pan to freshen them, after washing them under the faucet.” But he advises cooks to inspect the entree “looking for hairs and foreign pieces of food that do not complement the dish.”

Lately I’ve found myself eager to eat at home.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.