It seems pretty certain that restaurants of the 19th century were far less sanitary than they are today, and that employee hygiene, though still a factor now, was far worse. There were few mechanical dishwashers, no electrical refrigeration, and little understanding of the dangers of foodborne illnesses.

It wasn’t until the 1880s that science threw a spotlight on the subject and the concept of “ptomaine poisoning” developed, identified as alkaline substances formed during animal decomposition. The term ptomaine continued in use in the popular media even into the late 1970s, despite being scientifically questioned for decades and totally discredited by the 1930s. Scientific authorities pointed out that although ptomaines were real, meat would need to be in such an advanced state of decomposition at that point that no human, no animal, would touch it.

Soon after the ptomaine theory of illness was introduced in the 1880s, newspapers began reporting on its victims, many of them restaurant goers. For example, in 1899 the San Francisco Chronicle produced a story about a man who experienced cramps, vomiting, headache, and dizziness two hours after eating ham in a restaurant. A doctor said he had suffered ptomaine poisoning.

Given the documented history of food adulteration, it’s certainly believable that bad meat was often knowingly served in cheap restaurants. Some patrons believed they had been served decomposing meat that was smothered in sauce to hide it. Americans were generally averse to sauces, and whether it was due to fear of poisoning or the sense they were “foreign” is a good question. Probably both.

Eggs also fell under suspicion. Advice given to women shoppers by Harper’s Bazaar magazine in 1896 seems wise. It observed that “One hears of more sick results from salads than any other dish.” Salad at that time did not typically refer to vegetable salad but rather to chicken or other meat salads dressed with mayonnaise. In these cases it was likely that eggs used in mayonnaise caused Salmonellosis. The article recommended ordering “something hot, and better still if it is cooked for you,” which was reasonable advice.

What may have limited the overall incidence of foodborne illness in the 19th century was simply that then fewer people ate in restaurants, most restaurants were small and served few meals, and food production was smaller in scale and more localized so that the reach of contaminated food was reduced. Of course, since symptoms of foodborne illnesses don’t show up until between 10 hours to days later, it was unlikely then, as now, that most were identified or reported as such.

The association of sickness with restaurants began to play on the public’s imagination in the early 20th century. In summer 1908 a lunchroom waiter offered his thoughts: “If you must eat meat [in] this hot weather, select anything but hash or a Brunswick stew. If you insist on a finger bowl, have the man who serves you fill it in your presence. If you drink water at meals, make a private arrangement with your waiter. And if you must have buttered toast with your breakfast, don’t read this story.”

No doubt the waiter’s warnings were correct. A 1929 article in Restaurant Management magazine claimed that 25 years earlier few restaurants could have met modern sanitary regulations. The author said that most used lard cans for cooking, had no dishwashing machines and kitchens full of flies. Most also saved scraps from customers’ plates, left them sitting out for hours, and served them a second time – which explains why customers were suspicious of hash and stews.

As of 1925 the biggest known outbreaks of foodborne illness in the U.S., with the most fatalities, resulted from typhoid-infected oysters from polluted Long Island waters. The problem was not uncommon in the early 20th century, and caused a drop in oyster consumption. Yet in 1925 outbreaks sickened more than 1,500 people in New York, Chicago, and Washington D.C., with 150 deaths. There is no report of how many of those afflicted ate the oysters in restaurants, but it’s likely most did.

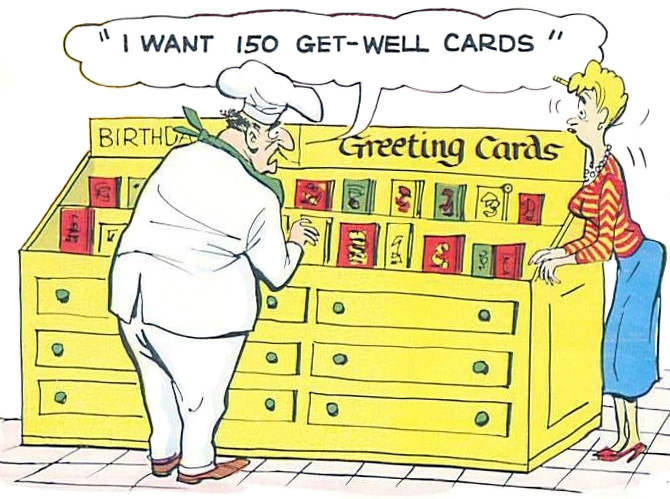

Generally, tracing reported cases to their source has always been quite difficult and most are not reported at all. Victims often think they have the mythical “24-hour flu.” Or they might attribute their distress to the last meal they ate in a restaurant when the source could well have been something consumed days earlier. In the case of Campylobacter, it has been estimated that as many as 2M people are afflicted each year (though not solely from restaurant meals), leading to more than 10,000 hospitalizations. Salmonella may afflict somewhat fewer people but causes more hospitalizations and deaths. [Above: 1989 cartoon still using the term “ptomaine”]

If restaurants seem to loom large in food poisoning history, that is at least partly explained by the greater ease in identifying cases when there is an outbreak where a group of people have eaten the same thing.

In more recent decades restaurant outbreaks have received quite a bit of public attention. And, although restaurants are cleaner and more careful than in the past, food perils have not gone away. In fact pathogens recognized after 1990 such as E. coli O157:H7, Listeria, and Campylobacter are some of the most dangerous. And it is not just protein food that is risky, but also fresh produce that has been contaminated by exposure to infected animals or water.

Norovirus is the most common variety of foodborne illness, and is found in fruits and vegetables and oysters. Its symptoms are flu-like, and, unlike bacterial agents, its spread is aided by transmission from infected persons, particularly in close environments such as cruise ships.

As news of outbreaks goes, it tends to focus on chain restaurants such as McDonald’s, Jack in the Box, Sizzler, Burger King, and others. Often that is less an indicator of their bad practices than it is a result of a massive industrial food processing system they are part of, marked by risky methods of raising animals, long distance transport, and other profitable economies of scale.

In the case of one large supplier, Hudson Foods, outbreaks resulted in a 1997 recall of 25M lbs. of beef patties possibly contaminated with E. coli. As a result as many as a fourth of Burger Kings nationwide had no burgers to sell for up to two days. After Listeria was discovered in its turkey deli meats, processor Pilgrims Pride set a new record in 2002 by recalling 27.4M lbs. of its products that had been distributed to restaurants, food stores, and school cafeterias.

And yet it wasn’t just large suppliers and distributors that were to blame. Outbreaks of E. coli and Salmonella in Chipotle outlets across the county in 2015 were not believed to be linked to large-scale suppliers but to the company’s mission of sourcing fresh food from small, local farmers.

Despite today’s threats, however, it’s probably as safe to eat in restaurants as it is at home.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.