Of course he wasn’t the only “sociopath” ever to become a restaurateur, but Michael Romanoff was very likely the most flamboyant. He was clever, spoke with a British accent, and dressed impeccably. His sense of style never left him. Imprisoned in NYC’s Tombs in the 1920s, he reportedly made quite an impression by strolling in the exercise yard with a walking stick. This story could be false, though, because not only did he twist the facts perpetually but so did some of the journalists who covered his bizarre 30-year career as a con-man.

Of course he wasn’t the only “sociopath” ever to become a restaurateur, but Michael Romanoff was very likely the most flamboyant. He was clever, spoke with a British accent, and dressed impeccably. His sense of style never left him. Imprisoned in NYC’s Tombs in the 1920s, he reportedly made quite an impression by strolling in the exercise yard with a walking stick. This story could be false, though, because not only did he twist the facts perpetually but so did some of the journalists who covered his bizarre 30-year career as a con-man.

He came to the attention of the press in 1910 when he presented himself as the grandson of England’s premier Gladstone in order to obtain two cameras on credit. He was unmasked as a former juvenile delinquent named Gilbert E. Gerguson. By the early 1930s he had used at least 17 aliases, including his favorite, Prince Michael Romanoff, younger brother of the former czar of Russia, Nicholas II. Although his “real” name is widely accepted as Harry F. Gerguson, I suspect it was actually Michael Romanoff, from Brooklyn. U.S. immigration authorities, however, were convinced he had been born outside this country and deported him every chance they got, about 10 times.

He claimed to have spent seven years of his life in jail. At times, when not sponging off rich patrons, stowing away on luxury ocean liners, or successfully passing bad checks, he was penniless and went hungry. He may have spent time in a mental hospital and attempted suicide at least once. Although he was sometimes described as a former pants presser, oil field worker, and buttonhole maker, it was not his style to hold a regular job although he once managed a farm in Virginia for over a year, possibly his longest gig.

He claimed to have spent seven years of his life in jail. At times, when not sponging off rich patrons, stowing away on luxury ocean liners, or successfully passing bad checks, he was penniless and went hungry. He may have spent time in a mental hospital and attempted suicide at least once. Although he was sometimes described as a former pants presser, oil field worker, and buttonhole maker, it was not his style to hold a regular job although he once managed a farm in Virginia for over a year, possibly his longest gig.

He never apologized for his lifestyle. Quite the contrary. In 1933 he declared, “For years I have been supplying adventure, by proxy, to those who have desired it. I have given more enjoyment, I think, than I have received.” By then everyone knew he was no prince, but he defended himself by saying, “At least I have the attitude of a prince – I have lived courageously and have, I think, put up the stock of princes.” Well, the stock of princes wasn’t terribly high in the 1930s and, courageous or not, he engaged in some shady activities.

He never apologized for his lifestyle. Quite the contrary. In 1933 he declared, “For years I have been supplying adventure, by proxy, to those who have desired it. I have given more enjoyment, I think, than I have received.” By then everyone knew he was no prince, but he defended himself by saying, “At least I have the attitude of a prince – I have lived courageously and have, I think, put up the stock of princes.” Well, the stock of princes wasn’t terribly high in the 1930s and, courageous or not, he engaged in some shady activities.

His life improved immensely when he became a frankly fake prince rather than a fraudster trying to pass for Russian royalty. And where better to be what he called a “real phony” than Hollywood? He opened a restaurant there around 1940 which quickly became one of Hollywood’s famous haunts. By then he was 47 or 50 years old, depending upon which birthdate you accept. According to various newspaper stories, the restaurant’s capital was put up by director Darryl Zanuck, writer Robert Benchley, and others. In 1951 it moved to South Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, and somewhat later spread into San Francisco and Palm Springs.

The Hollywood Romanoff’s was a celebrity den where Mike entertained his guests — sometimes by snubbing them. How much time he spent supervising staff or bothering himself with mundane chores such as buying provisions or going over the books is unclear, as is the quality of the cuisine. By one account it was so-so but was upgraded to “above-average” in the late 1950s. An undated menu shows numerous dishes with Stroganoff and Romanoff suffixes. He made a good income, but by December 1962 business had fallen off to such a degree that the Beverly Hills Romanoff’s closed. I have not been able to determine the fate of the other two locations.

The Hollywood Romanoff’s was a celebrity den where Mike entertained his guests — sometimes by snubbing them. How much time he spent supervising staff or bothering himself with mundane chores such as buying provisions or going over the books is unclear, as is the quality of the cuisine. By one account it was so-so but was upgraded to “above-average” in the late 1950s. An undated menu shows numerous dishes with Stroganoff and Romanoff suffixes. He made a good income, but by December 1962 business had fallen off to such a degree that the Beverly Hills Romanoff’s closed. I have not been able to determine the fate of the other two locations.

Mike’s story was clearly movie material, yet it seems that two announced films (“Ellis Island,” “The Incredible Romanoff”) never appeared. He had small parts in numerous films, sometimes playing a butler, aristocrat, or himself as restaurateur. In 1958 Congress voted to grant him permanent resident status and he became a naturalized citizen.

© Jan Whitaker, 2010

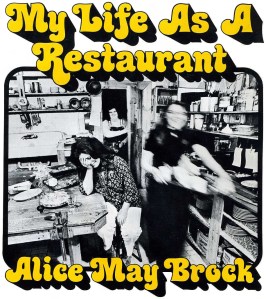

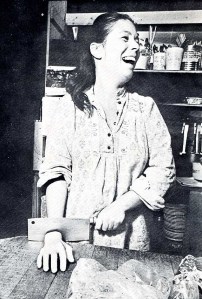

In interviews and in her two books Alice espoused the value of fresh ingredients, garlic, meals with friends, and an experimental approach to cooking. Her words convey a free-wheeling, irreverent outlook. Some examples:

In interviews and in her two books Alice espoused the value of fresh ingredients, garlic, meals with friends, and an experimental approach to cooking. Her words convey a free-wheeling, irreverent outlook. Some examples:

Don ran into trouble with the postwar longshoremen’s strike and decided to limit his Honolulu Beachcomber to a drinking spot. By the early 1960s he was also in the restaurant business, operating a South Seas Cabaret Restaurant, a Colonel’s Plantation Steak House, a Colonel’s Coffee House, and at least one restaurant boat. Cora’s popular Chicago Don the Beachcomber was named one of the top 50 US restaurants in 1947. She soon opened another location in Palm Springs and by 1972, when it was acquired by Getty Financial, the chain had 6 or 7 units.

Don ran into trouble with the postwar longshoremen’s strike and decided to limit his Honolulu Beachcomber to a drinking spot. By the early 1960s he was also in the restaurant business, operating a South Seas Cabaret Restaurant, a Colonel’s Plantation Steak House, a Colonel’s Coffee House, and at least one restaurant boat. Cora’s popular Chicago Don the Beachcomber was named one of the top 50 US restaurants in 1947. She soon opened another location in Palm Springs and by 1972, when it was acquired by Getty Financial, the chain had 6 or 7 units.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.