This is such a big subject that I’m focusing only on the two world wars of the 20th century. Both wars made restaurants more central to modern life. The restaurant industry emerged larger and with a more diverse patronage. It was more organized, more independent from the hotel industry, more consolidated, more streamlined in its practices, and less European in its values and orientation.

World War I

● The effects of World War I were felt before the US declared war against Germany in spring of 1917. Americans living abroad, such as artists in Paris, returned to the U.S. Some of them returned to Greenwich Village to develop and nurture something quite foreign here, namely café culture.

● The effects of World War I were felt before the US declared war against Germany in spring of 1917. Americans living abroad, such as artists in Paris, returned to the U.S. Some of them returned to Greenwich Village to develop and nurture something quite foreign here, namely café culture.

● In Washington DC, wartime bureaucracy required more office workers, increasing the ranks of working women, a new and lasting restaurant clientele. As the female workforce grew nationwide, women’s restaurant patronage from 1917 to 1927 went from 20% of all customers to 60%, and became foundational to the future growth of modern restaurants. Around the country low-priced restaurants accustomed to male patronage were forced to add women’s restrooms.

● Many foreign nationals who had worked as cooks, kitchen help, and waitstaff in restaurants left to join armies of their native lands. The restaurant labor shortage worsened when the draft began in 1917 and foreign immigration ceased. Immigrants were replaced by Afro-American and white women who migrated to cities. Serving in restaurants became female dominated.

● The war brought women to the forefront of food service. Home economists rallied to the cause by opening restaurants. In Washington DC, a graduate of Cornell’s home economics program began a cafeteria for war workers nicknamed the “Dom Econ Lunchroom.”

● Wartime prohibition followed by national prohibition in 1919 dealt a blow to fine dining. The culinary arts of European-trained chefs fell into disuse as many elite restaurants closed after a few lean years.

● Immigrant tastes were reworked by WWI. Those who served in the US military became accustomed to the American diet of beef and potatoes, white bread, and milk, as did Southerners used to “hogs and hominy.” Meanwhile on the homefront, certain “foreign” foods, such as pasta and tomato sauce, were admitted into the mainstream middle-class diet, in this case because Italy was an ally.

● Wartime also stimulated a more business-like attitude on the part of restaurants which now had to work smarter to produce profits. They adopted principles of scientific management — for example, they began keeping books! And they standardized recipes to turn out consistent food despite changes in personnel.

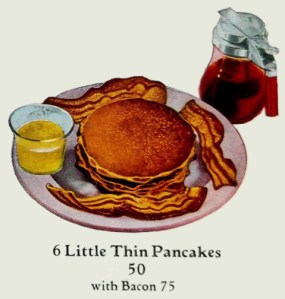

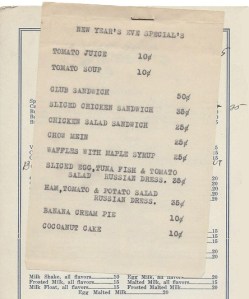

● The decade after World War I saw the rise of sandwiches, salads, milk, and soft drinks replacing the heavy restaurant meals served before the war.

● The decade after World War I saw the rise of sandwiches, salads, milk, and soft drinks replacing the heavy restaurant meals served before the war.

● During the Depression WWI veterans demonstrated and lobbied for their long-overdue soldiers’ bonuses. Many used the bonuses to open hamburger stands and other roadside businesses such as the Kum Inn on Long Island.

World War II

● Many of the same kinds of effects were felt after the Second World War, sometimes more strongly because of the increased duration of the conflict. Immigration came to a halt, furthering the “Americanization” of restaurants. Women trained in institutional management and home economics continued to enjoy expanded opportunities and prestige. Two home economists in Minnesota saw their quantity cooking manual adopted by the military.

● During the war, the average American patronized restaurants as never before. Southern California restaurants were overwhelmed as an estimated 250,000 workers in war plants who lacked housekeeping facilities turned to public eating places for their meals.

● Food rationing dramatically increased restaurant patronage. In January 1943 the Office of Price Administration announced that the public would not need ration coupons in restaurants. Within weeks after rationing began restaurants were mobbed. In Chicago, Loop restaurants experienced a 25% increase in business. By October of that year patronage in NYC restaurants had doubled.

● Also stimulating the eating-out boom were generous business expense accounts which, said the NYT, “grew into a fat-cat fringe during World War II.” These benefits were meant to compensate workers who could not be granted raises because of government-imposed wage and salary freezes and employers’ wish to avoid paying excess-profits taxes. To retain valued employees they instead gave pensions, medical care plans, stock options, and generous expense accounts. Expense accounts led to the creation of the first nation-wide credit card, sponsored by The Diner’s Club.

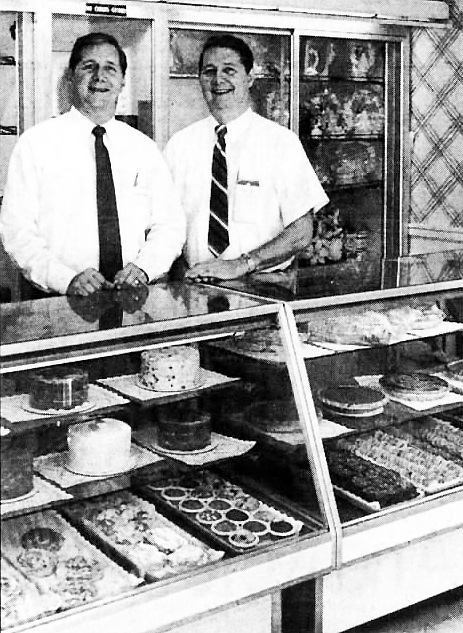

● Already in 1944 the National Restaurant Association was looking forward to augmenting short staffs with some of the estimated 300,000-500,000 military cooks and bakers to be demobilized at war’s end. Tuition under the GI bill lured thousands into further training as restaurant cooks, managers, and proprietors.

● After fighting a war against a “master race” ideology, returning black GIs strongly resisted racial discrimination in American restaurants. In Seattle the NAACP filed complaints when “white only” signs appeared or blacks experienced deliberately poor service. The signs were meant for Japanese returning from internment camps as well. [Ben Shahn photo, FSA]

● Unlike before the war, eating in restaurants was no longer an unfamiliar experience for most Americans. A manual issued by the New York State Restaurant Association in 1948 proclaimed that restaurants were serving more than 15.5B meals annually. A sociologist attributed the emergence of the sassy waitress to wartime’s broadening clientele which included a “new class of customers, who were considered particularly difficult to deal with.”

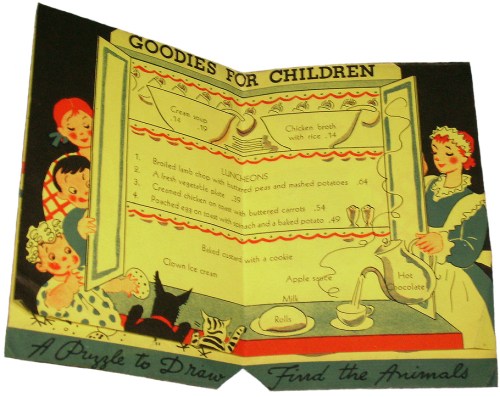

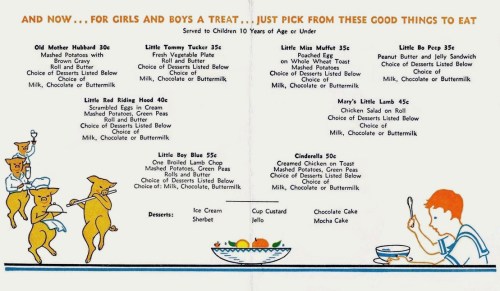

● Family patronage, encouraged by a wartime increase in employment of married women, continued to grow after the war. A trade journal counseled operators of suburban restaurants to “be especially nice to children.” In Denver, the average family was said to eat out three or four times a month, a rate unheard of before the war.

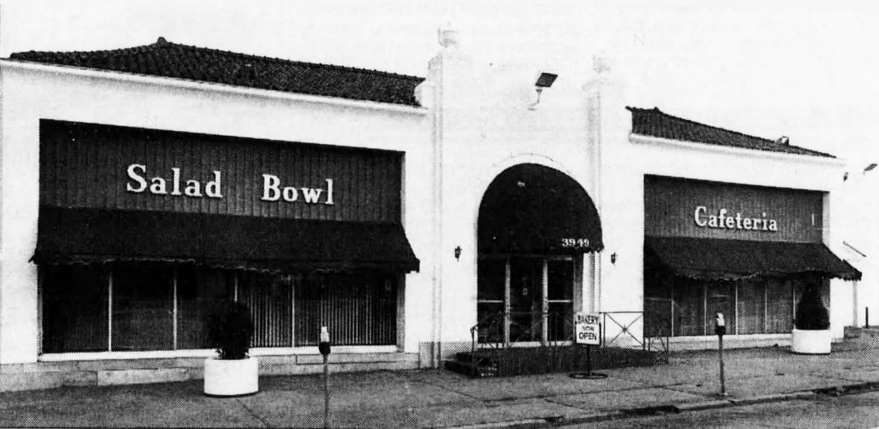

● Another lasting effect of wartime eating-out habits was increased restaurant patronage in the South, a region where there had been few restaurants and little restaurant culture. Northern industries were already moving south in 1941, but also, as the restaurant industry noted in May of that year, “most of the Army activity is in the Southern States,” a fact they believed made it the area with the “greatest opportunity for restaurant expansion.”

● A number of common menu items can be attributed to World War II. Restaurant patrons learned how to eat lobsters, which were plentiful because they were not rationed. Pizza parlors proliferated because pizza was also simple to serve. Conscripted country dwellers were introduced to sea foods in military service. Veterans who had served in the South Pacific discovered a liking for Polynesian food.

● A number of common menu items can be attributed to World War II. Restaurant patrons learned how to eat lobsters, which were plentiful because they were not rationed. Pizza parlors proliferated because pizza was also simple to serve. Conscripted country dwellers were introduced to sea foods in military service. Veterans who had served in the South Pacific discovered a liking for Polynesian food.

● War spurred the use of new food products by the military, including frozen food. In a remarkably short time, the restaurant industry, which had previously preferred fresh to processed food, adopted frozen foods and by 1955 they accounted for 20 to 40% of their supplies. With the rise of frozen food and other war-facilitated convenience foods came restaurant stalwarts of the 1960s: French fries, breading mixes, and cheese cake.

● Along with frozen foods came new technologies for their preparation, in particular microwave ovens and quick-recovery griddles, both military spinoffs. The RadarRange, presented at the National Hotel Exposition in 1947, was developed by Raytheon using principles of infrared technology developed during the war. It not only permitted food to be cooked lightening fast but also made reheating pre-cooked frozen entrees possible. Another marvel was the Rocket Griddle which featured fast heat recovery that enabled frozen food to be cooked without defrosting.

● The development of the air freight industry following WWII, stimulated by the availability of trained pilots and surplus airplanes, permitted restaurants to obtain foods from locations around the world. A restaurant called Imperial House in Chicago was approached by two former Air Force fliers who proposed to fly in king crabs from Alaska by freezer plane. By 1952 the restaurant was bringing strawberries from Florida and California, bibb lettuce from Kentucky, salmon from Nova Scotia, pheasant and venison from South Dakota, grouse from England, and paté from France.

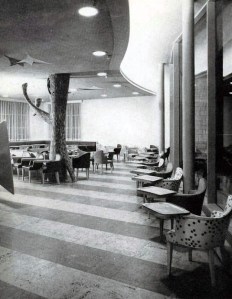

● Last but not least, the ideal of organizational efficiency was stimulated by both wars. The World War II postwar period saw the rise of a much larger food service industry.

And, of course, this brief survey is far from complete.

© Jan Whitaker, 2019

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.