When journalist Fanny Fern took up her pen, readers knew wicked pronouncements would flow. Her fans loved it. Of course she also had many detractors who disapproved of her bold opinions and her feminism.

When journalist Fanny Fern took up her pen, readers knew wicked pronouncements would flow. Her fans loved it. Of course she also had many detractors who disapproved of her bold opinions and her feminism.

For twenty years starting in 1851 Fanny Fern wrote about her favorite subjects, “Men, Women, and Things.” Her essays appeared in newspapers and were later collected in books. The first collection, Fern Leaves from Fanny’s Portfolio (1853), sold 80,000 copies in a matter of weeks. She was said to be the second highest paid woman writer in America after Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Fanny Fern was the pen name of Sara Willis, born in 1811 in Maine and raised in Boston. After her first husband died, she accepted an offer of marriage to a man who became abusive. Her literary career was launched by the need to earn a living for herself and her three children after she left him in 1851.

Food and dining out at dinner parties and restaurants were topics that occasionally appeared in her columns. Two of her collections were named for food – Ginger-Snaps and Caper-Sauce. She prefaced Ginger-Snaps with the following:

Despite her acerbic style, even those who were its targets treasured her and over the course of her life she sold hundreds of thousands of books in the U.S. and England. An entry about her in American Women (1897), noting hers was “the most widely known and popular pen-name of the last forty years,” praised her for “wit, humor and pathos.”

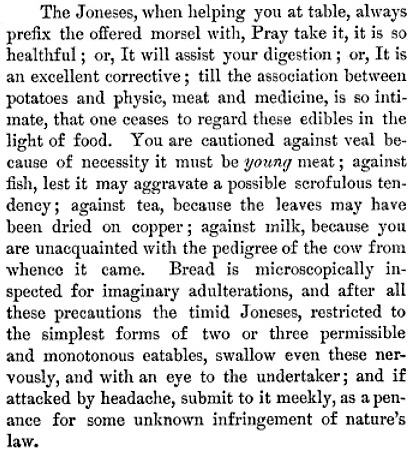

Her style is captured in a short piece called “The Amenities of the Table” in which she described attitudes toward food as represented by three very different couples. Her depiction of the Joneses strikes a note today.

In 1854 she moved from Boston to New York City where she wrote for the New York Ledger (and married author James Parton). No doubt she became familiar with Taylor’s, the glitzy, mirrored, pseudo-posh Broadway restaurant [pictured below] she featured in an essay called “Feminine Waiters at Hotels.” Always protective of women workers, she advised miserable seamstresses to throw their thimbles at their employers and rush to Taylor’s, which had just begun hiring women as servers. But she suggested that they take good care of themselves: “Stipulate with your employers, for leave to carry in the pocket of your French apron, a pistol loaded with cranberry sauce, to plaster up the mouth of the first coxcomb [“dude,” “masher”] who considers it necessary to preface his request for an omelette, with ‘My dear.’”

The servers, she observed, would surely encounter all kinds of overdressed patrons trying to impress others and would “get sick of so much pretension and humbug,” But, she added, “Never mind, it is better than to be stitching yourselves into a consumption over six-penny shirts; you’ll have your fun out of it. This would be a horribly stupid world, if everybody were sensible.”

Sara Willis Parton died in 1872. Her life story is told in Fanny Fern: An Independent Woman by Joyce W. Warren (Rutgers University Press, 1992).

© Jan Whitaker, 2015

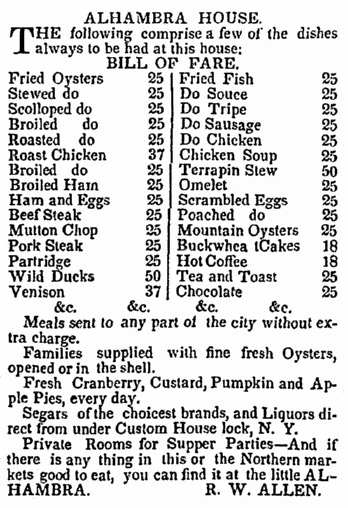

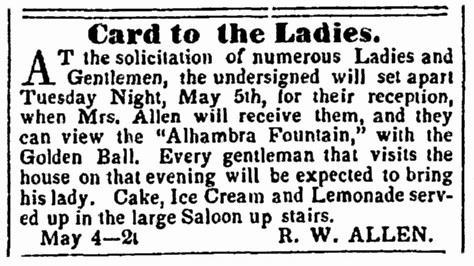

In the 1850s the great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of New York’s Central Park, traveled through the South to investigate the institution of slavery. His observations were published in three volumes which were influential in turning readers against slavery. Around 1857 he traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, where he stayed at the Commercial Hotel. Although it was considered a first-class establishment, things did not go well for Frederick in the dining room as his journal entry for March 20, below, reveals. Among the dishes appearing on the not-too-elegant menu were “Beef heart egg sauce,” “Calf feet mushroom sauce,” “Bear sausages,” “Fried cabbage,” and, for dessert, “Sliced potatoe pie.” Better than whole potato pie, I guess.

In the 1850s the great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of New York’s Central Park, traveled through the South to investigate the institution of slavery. His observations were published in three volumes which were influential in turning readers against slavery. Around 1857 he traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, where he stayed at the Commercial Hotel. Although it was considered a first-class establishment, things did not go well for Frederick in the dining room as his journal entry for March 20, below, reveals. Among the dishes appearing on the not-too-elegant menu were “Beef heart egg sauce,” “Calf feet mushroom sauce,” “Bear sausages,” “Fried cabbage,” and, for dessert, “Sliced potatoe pie.” Better than whole potato pie, I guess.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.