Appetizers became a prelude to a meal when many Americans suffered digestive problems in the 18th and 19th centuries. The idea was that appetizers were various items of fare that would help stimulate an appetite in those who were out of sorts. They could be foods, medicinal tonics, or alcoholic drinks.

Due to the strong influence of English customs in early America, the notion of taking something before a meal as a digestive stimulant more often than not meant an alcoholic drink rather than food. So the English term most often used – whets – referred primarily (though not exclusively) to drinks before dinner. The French equivalent of whets would be aperitifs.

As a term, however, “whets” did not appear on printed menus as far as I’ve discovered.

Drinks that usually served as whets/appetizers/aperitifs included rum, brandy, sherry, vermouth, champagne, and Dubonnet. In the 20th century especially, cocktails became a favorite pre-dinner drink.

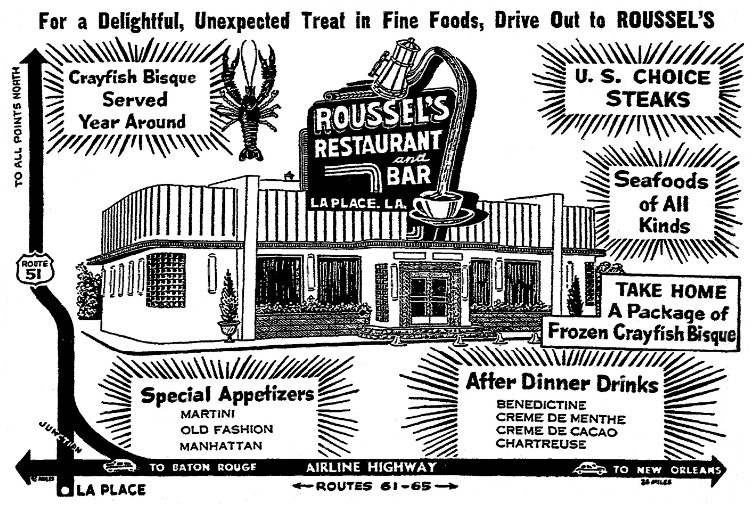

While many diners began their restaurant meals with a cocktail, the drink itself was rarely referred to as an appetizer or whet after the 19th century. So I was quite surprised to find a Louisiana roadhouse restaurant listing Martinis, Old Fashion[ed]s, and Manhattans as appetizers in a 1956 advertisement!

As food, appetizers were usually lighter things consumed before the heavier Fish, Entrées, and Roasts courses typical of formal meals of the 19th century.

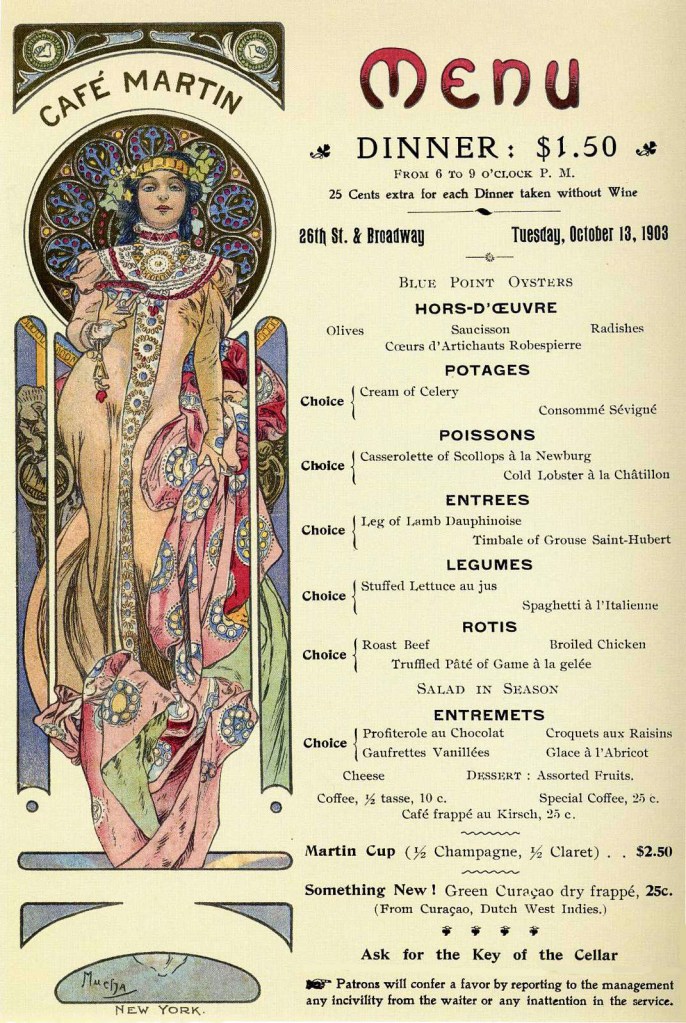

The word “Appetizer” itself though does not seem to have come into common use in American restaurants until the early 20th century. The term “Hors d’Oeuvres” was also used, as was “Relishes.” The French “Hors d’Oeuvre” tended to be used by higher-priced restaurants, such as New York’s Cafe Martin [1903], that sought to create an aura of continental elegance and sophistication.

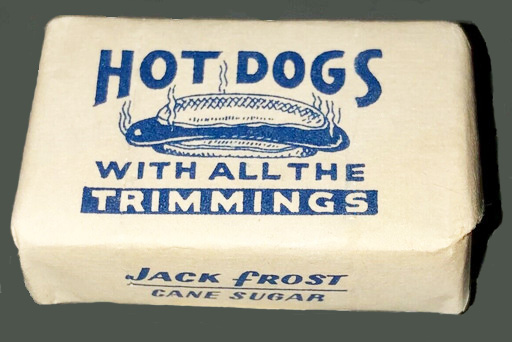

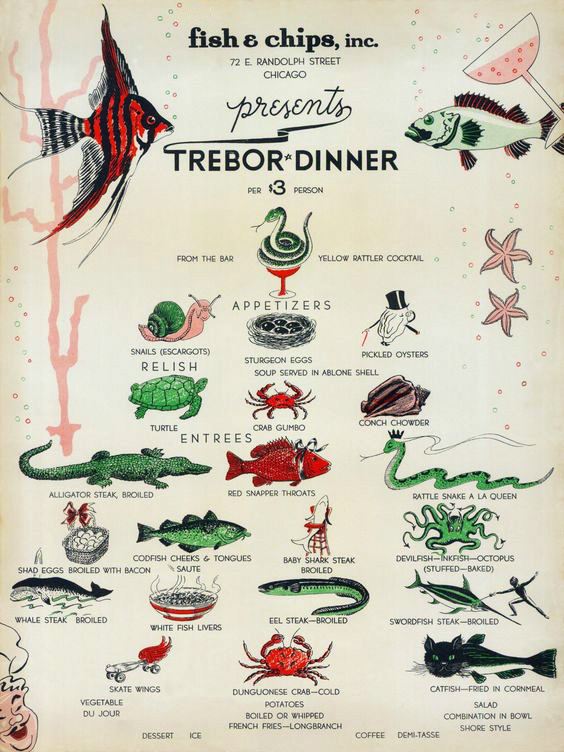

Relishes initially referred to light vegetable foods, sometimes sauces. In the mid-19th century they were sometimes served just before the sweet courses, but by the early 20th century the category had risen to near the top of menus. Over time, the foods that had once appeared separately as Relishes tended to become included under the heading Appetizers.

But it’s almost impossible to firmly settle the question of what kinds of foods are found in the various categories – Relishes, Hors d’Oeuvres, Canapes, Appetizers, etc. The categories are loose and highly variable. One restaurant’s Relishes are another’s Hors d’Oeuvres.

A distinction is often made between Hors d’Oeuvres and Appetizers, stressing that the latter are eaten at the table in restaurants while Hors d’Oeuvres are one-bite morsels offered by servers to standing guests before they are seated. This distinction may hold for catered events but not for restaurants where there is no hesitation about using Hors d’Oeuvres as a general category.

Also confusing are the menus listing “Hors d’Oeuvres” as a selection under the headings Appetizers or Relishes. In 1917 a menu from San Francisco’s Portola Louvre actually put Hors d’Oeuvres under the heading Hors d’Oeuvres, along with caviar, sardines, celery, etc. Imagine a waiter asking, “Would you like some Hors d’Oeuvres for your Hors d’Oeuvres?

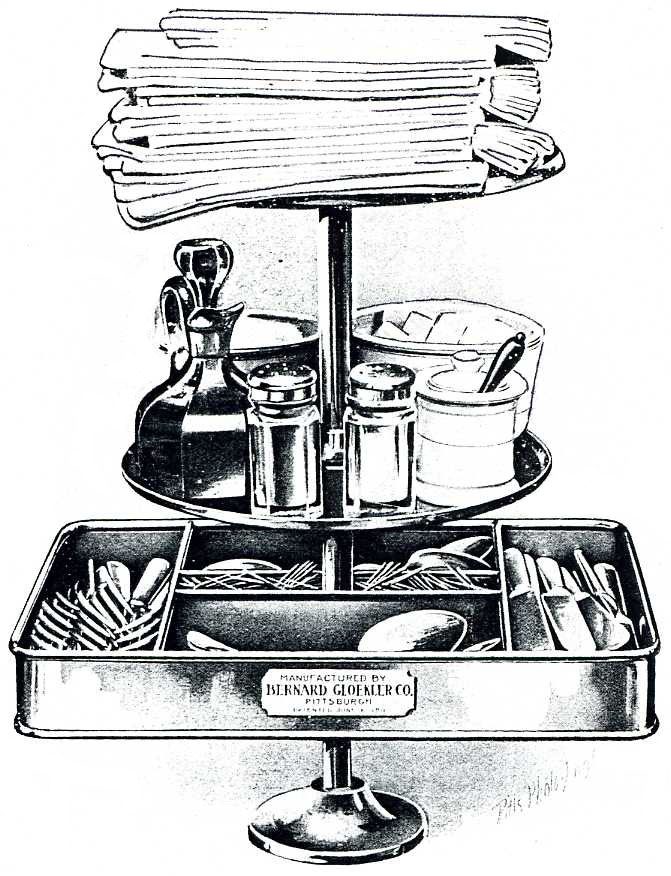

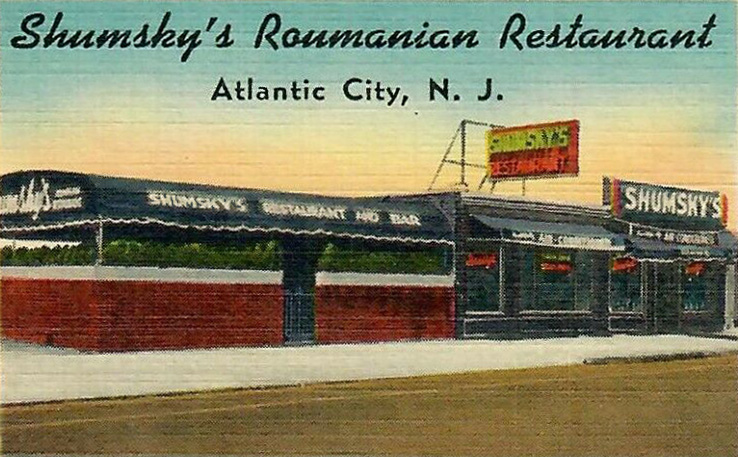

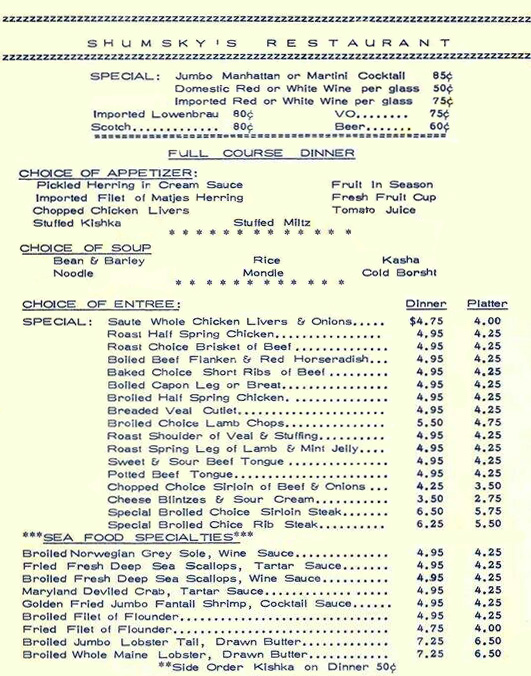

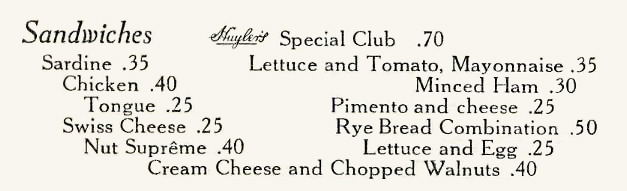

Until the 1960s and 1970s, the food items that were most commonly offered as beginnings to restaurant dinners were prepared simply and usually served cold. They have included: Fresh vegetables such as celery, radishes, artichoke hearts, and spring onions. Fresh fruits, including grapefruit and melons. Pickled and preserved vegetables, whether olives, beets, peppers, or traditional cucumber pickles. Preserved fruit combinations such as chutney and chow chow. Juices of tomato, grapefruit, pineapple, sauerkraut, and clams. Fresh seafoods — oysters, shrimp, lobster, scallops, and crab. And cured, smoked, pickled, deviled, and marinated meats and seafood/fish, including Westphalia ham, sausages, prosciutto, caviar, paté de foie gras, eels, herring, sardines, salmon, anchovies, and whitefish.

I am impressed that celery – en branche, hearts, a la Victor, a la Parisienne, Colorado, Kalamazoo, Pascal, Delta, stuffed, etc. – stayed on menus from the 19th century until long after World War II.

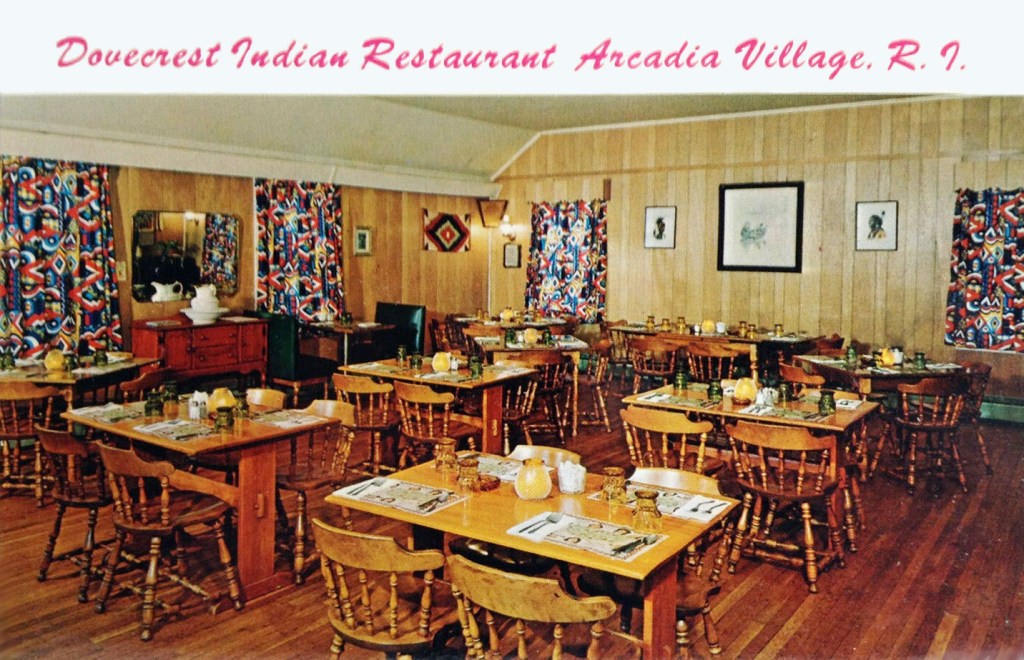

Heavier, more substantial, and often heated Appetizers seem to have been introduced post-WWII mainly by restaurants designated as Polynesian, Cantonese, and Mexican/Latin. In 1960 New York’s La Fonda del Sol offered appetizers such as Avocado Salad on Toasted Tortillas, Little Meat and Corn Pies, Grilled Peruvian Tidbits on Skewers, and Tamales filled with chicken, beef, or pork. A 1963 menu from a Polynesian restaurant called The Islander dedicated a whole page to its “Puu Puus (Appetizers)” that included ribs, chicken in parchment, won tons, and fried shrimp. The assortment was quite similar to the offerings at Jimmy Wong’s Cantonese restaurant in Chicago shown above.

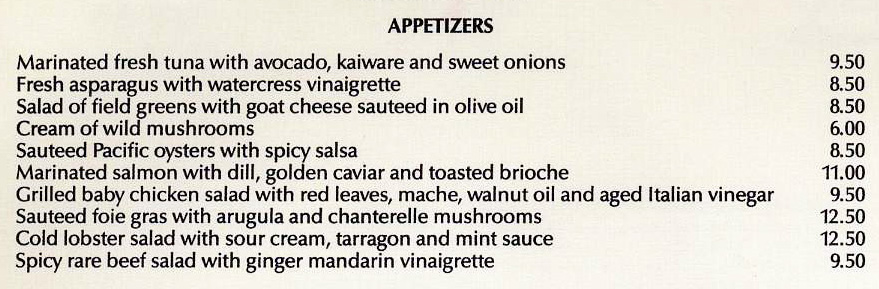

By the 1980s, many restaurants featured appetizers that would now likely be called “Small Plates” or items for “grazing.” Two or three were substantial enough to make up a dinner in themselves, as demonstrated here by a rather expensive Spago menu from 1981.

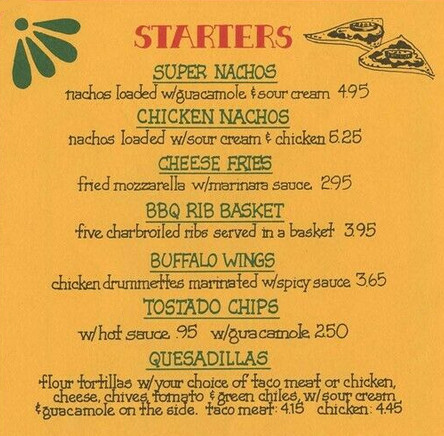

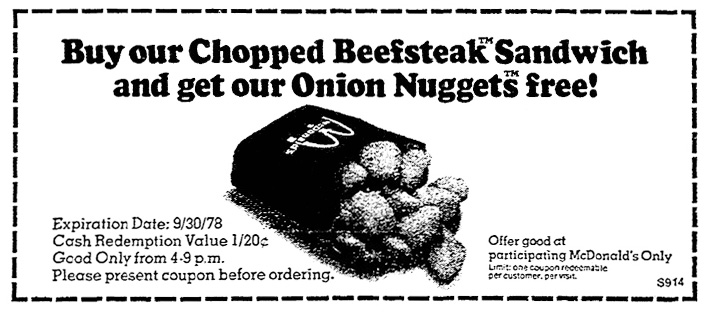

If grazing was a form of “light eating,” that could not be said of the appetizers introduced in the 1970s and 1980s by casual dinner house chains such as TGI Friday, Chili’s [1987 menu above], and Bennigan’s. Now the idea of an appetizer was completely turned on its head. Far from a light morsel that would induce appetite in someone with digestive issues, it became a digestive issue in its own right — deep fried and loaded with fat. The menus of leading casual dinner chains overflowed with “Starters” such as deep-fried breaded cheese, “loaded” potato skins, cheese fries [pictured at top of post], and heaping piles of nachos laced with pico de gallo and cheese. Diners might need a 19th-century digestive tonic after dinner.

© Jan Whitaker, 2021

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.