Historically, the Romanian* restaurants that received the greatest attention from the press have been those in New York City. In 1901 the population of Romanians in New York City as a whole was estimated to be 24,000, with about 15,000 of those in the Romanian quarter on the Lower East Side. There were said to be 150 restaurants, 200 wine cellars, and 30 coffee houses kept by Romanian Jews. Favorite foods included broiled meats, goose pastrami, cabbage rolls, polenta, and spicy skinless sausage. Seltzer and red wine figured largely as drinks.

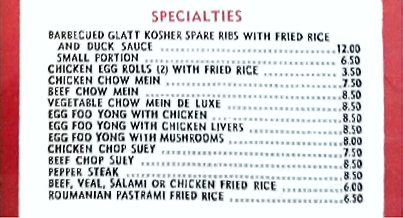

Not all Jewish-operated Romanian restaurants followed kosher law, but they were unlikely to have pork on the menu, the principal meat of Romanian cuisine and used in cabbage rolls (sarmale).

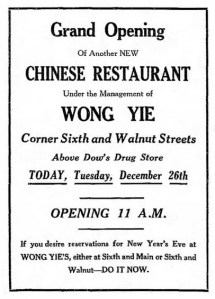

Immigration to this country began in the 1880s. It’s likely that the earliest Romanian restaurant in New York was one that began as a wine cellar in 1884 on Hester Street, and soon evolved into an eating place. Romanian immigrants were disproportionately male, working during the day and renting crowded floor space to sleep at night. Restaurants and coffee houses were not only places for meals and refreshment, but also community centers for these men, who were essentially homeless.

In his memoir An American in the Making (1917), Marcus Ravage explained that when he arrived in New York City in 1901, as soon as he made a few cents peddling on the streets he headed for a Romanian restaurant on Allen Street, where he ordered a ten-cent dinner of “chopped eggplant with olive-oil, and a bit of pot-roast with mashed potato and gravy.” Ravage expressed the difficulty he had in accepting American food and eating habits. When he went to college in Missouri in 1905, he reported that everything tasted “flat” to him, and that he “missed the pickles and the fragrant soups and the highly seasoned fried things and the rich pastries made with sweet cheese” he grew up with.

A Romanian dish from an East Side restaurant described in 1905 was a “hot and very piquant” round steak with peppers. The steak was cut into 3-inch-wide strips, slashed with a knife and marinaded in lemon juice and oil before being pan fried. Small red peppers were fried with it. Each diner took a pepper, opened it, and sprinkled the seeds on the meat.

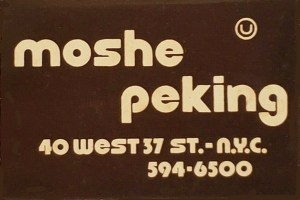

According to author Konrad Bercovici in Around the World in New York (1924), many of New York City’s Romanian restaurants were run by Jews, but often the proprietors were Greeks, Hungarians, or Germans, as was the case in Romania’s capital, Bucharest. Over time, it seems as though the fare served in these restaurants merged with what was becoming known as Jewish cuisine rather than remaining strictly Romanian. (Of course Romanian cuisine itself strongly reflected a blend of traditions.)

Some of New York’s Romanian restaurants developed into night clubs, with a grab-bag of acts bordering on vaudeville. Joseph Moskowitz was a world-famous cymbalom player, who began his restaurant career in 1913 with a wine cellar on Rivington street. Later he had restaurants with music and dancing on Houston, and then on 2nd Avenue in 1938 at Moskowitz & Lupowitz where dinners began at 85 cents. He sold his share in that restaurant a short time later and moved to Akron OH, where he often played at Gruhler’s Romany Restaurant.

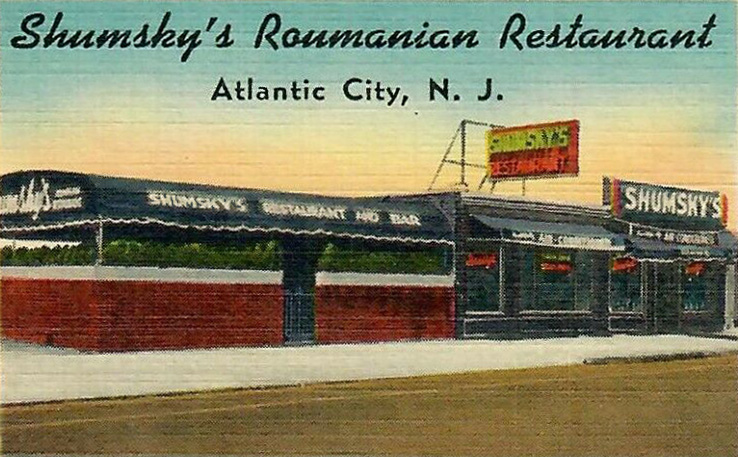

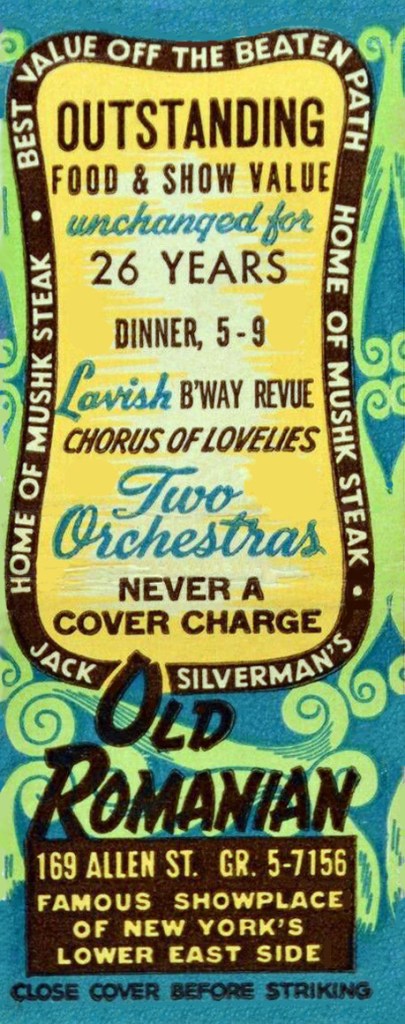

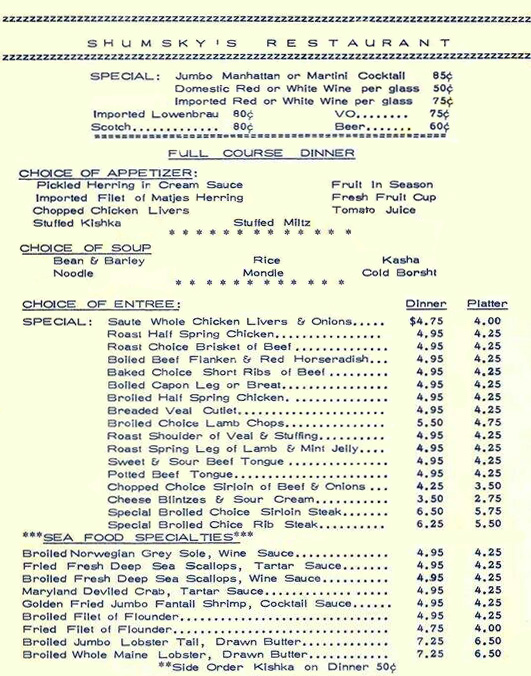

Other popular East coast night spots included Old Roumanian on Allen Street in New York and Shumsky’s Roumanian Restaurant and Bar in Atlantic City, established 1925, which advertised “New Kishka (sausage) Room” and “Dinner ‘Muscat’ Music” in 1952. At Sammy’s, on NY’s Chrystie street, which opened in 1975 and closed quite recently, entertainment was mainly in the form of extras placed on the table. They included a pitcher of chicken fat, fizz-your-own-seltzer, and for dessert a bottle of Fox’s U-Bet chocolate syrup, milk and two glasses for making an egg cream.

A bohemian version of a Romanian Restaurant was operated by Romany Marie in Greenwich Village. Sculptor Isamu Noguchi characterized it as “a sort of a transfer of the Paris café life to New York.” It’s likely this was true to some degree of many Romanian eating places which tended to exude a sense of good cheer and camaraderie all their own. [above: 1924 advertisement]

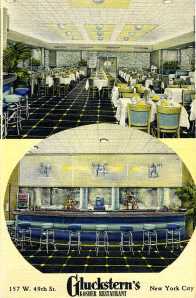

Many Romanian restaurants had prices in the reasonable range, with full dinners running from $1.00 to $1.25, but that was far from the case for the elegant restaurant in the Romanian House at the 1939 NY World’s Fair [shown above]. There the menu was in French, fresh caviar was $2.50, and a dinner was priced at $3.50, minus wine.

Outside of New York – in the late 19th and early 20th centuries before many Romanians dispersed into the larger population – there were Romanian colonies in other cities, both in the East and in the upper Midwest. Some were composed of Romanian Jews, but others, perhaps most, were communities whose members belonged to Catholic and Orthodox religions. Immigration to the U.S., almost nil from 1920 until the 1940s, resumed after World War II when the Soviets took over and continued through the 20th century and into the present.

It becomes harder to track Romanian restaurants in the later 20th century since they became less inclined to use Romanian as part of their names. But they certainly existed in Trenton, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Miami, Los Angeles, and many other cities. One reason they might not have been clearly identified as Romanian was expressed in 1990 by Felicia Zanescu, proprietor of Mignon European Restaurant in Los Angeles. When asked why she called it European rather than Romanian, she replied, “Who ever heard of Romania?” Nonetheless the menu was convincingly Romanian with its carp roe dip, eggplant paté, dill-accented white bean broth, fried cheese, sausages, cabbage rolls, etc.

© Jan Whitaker, 2021

* Before 1975 Romania was usually spelled Roumania or Rumania.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.