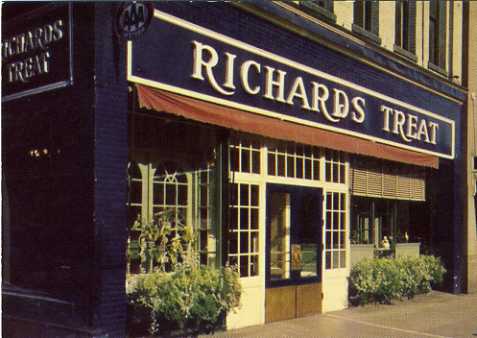

Over the weekend, at a vintage paper and postcard show in Boxborough MA, I found a charming diecut menu from a restaurant in Silver Spring MD. Established in 1930 by Olive and Harvey Kreuzburg, the landmark restaurant is still in operation today though no longer owned by the founding family.

Shown through the window is page 2 of the menu illustrated with a fireplace inscribed with a cryptogram. Can you figure it out? Hint: the riddle is said to have originated in England. (Click to enlarge. Answer below.)

Judging by the prices, this menu is from around 1950. A Tenderloin Steak dinner accompanied by French Fried Onions or Fresh Mushrooms, cost $2.25. It was served with soup, fruit relish, salad, three vegetables, a sherbet course, hot bread, dessert, beverage, and after dinner mints. By 1962, when the Kreuzburg’s son Richard ran the restaurant, that dinner had gone up to $6.00. Burgundy, Sauterne, Claret, and Blue Ribbon beer were available. All meals were served family style with bowls filled with enough for the entire table. Mrs. K assured guests that everything was prepared from scratch on the premises and under her supervision.

Judging by the prices, this menu is from around 1950. A Tenderloin Steak dinner accompanied by French Fried Onions or Fresh Mushrooms, cost $2.25. It was served with soup, fruit relish, salad, three vegetables, a sherbet course, hot bread, dessert, beverage, and after dinner mints. By 1962, when the Kreuzburg’s son Richard ran the restaurant, that dinner had gone up to $6.00. Burgundy, Sauterne, Claret, and Blue Ribbon beer were available. All meals were served family style with bowls filled with enough for the entire table. Mrs. K assured guests that everything was prepared from scratch on the premises and under her supervision.

Olive Kreuzburg was not new to the restaurant business when she and her husband took over the old toll house that had previously been the home of two other failed tea rooms. In 1923 it operated as the Seven Oaks Tavern where sky high prices must have contributed to its demise. Olive’s prior experience included running the dining room of the Hotel Wellesley in Clayton NY, a tea room in Miami FL called Mrs. K’s, and two tea rooms in Washington DC, one named Mrs. K’s, and the other Mrs. K’s Brick Wall Inn. Clearly using her abbreviated name served her well.

At its opening in 1930 the Silver Spring Toll House was listed in a DC newspaper under “Where to Motor and Dine.” At that time development had not sprung up around Mrs. K’s; although only “a 30-minute drive from the White House,” it was in the country. The early advertisement read: “This old Toll House with its charming furnishings and Terraced Gardens marks a delightfully smart Country Dinner Place.”

Getting through the Depression was no doubt aided by Duncan Hines’ recommendation of Mrs. K’s in his very first list of his favorite restaurants that he sent out to friends in a 1935 Christmas card. Later he expanded the list and published it as a book. In the 1937 edition, he said of Mrs. K’s, “You dine in the past here – so far as furnishings are concerned. Nothing is changed apparently from the Revolutionary days when it was built. Even the pretty girls who wait on you in Colonial dress seem to have been miraculously preserved from a more leisurely age when dining was a rite not to be passed over casually.”

Whether or not the building dated from the Revolution, the quaint restaurant was filled with antiques collected by the Kreuzburg’s.

The cryptogram explained:

If the grate be [great B] empty (m t), put coal on [colon].

If the grate be full, stop [ . ] putting coal on.

© Jan Whitaker, 2015

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.