In addition to collecting restaurant menus, photographs, postcards, business cards, matchcovers, etc., I also collect words. Here are some choice quotations by, for, and about restaurants ranging from 1880 to 1980 that I’ve carefully selected to reflect the progression of American restaurants and customers’ relation to them.

In my opinion, they convey a richer and truer sense of restaurant history than would a conventional “timeline.” Funny too.

1880 “Whenever I feel possessed of an appetite that has any stability about it I go to a place where I find butchers dining. There order the juicy steaks and the mealy potato.”

1880 “Whenever I feel possessed of an appetite that has any stability about it I go to a place where I find butchers dining. There order the juicy steaks and the mealy potato.”

1883 “The Restaurants and Cafes of Boston number nearly 500. Excepting those connected with hotels, there are not many worthy of particular mention.”

1884 “The waiters, with a dexterity which could only have been acquired through long practice, stood off and shied the dishes at the tables from a distance of three or four feet.”

1884 “The waiters, with a dexterity which could only have been acquired through long practice, stood off and shied the dishes at the tables from a distance of three or four feet.”

1888 “Eating is a matter of business with Americans. They do it as they perform all other kinds of work – on the rush.”

1891 “No time for persuasion is as good as meal time, and so Mr. Close has hung the walls of his eating-house with texts from the Bible wherever the space is not needed for bill of fare placards.”

1894 “When a waiter shoves a bill of fare under a man’s nose nine times out of ten he will look it over and then say: ‘Gimme a steak and some fried potatoes.’”

1895 “The whizz of the big ventilating fans, the cries of the waiters, the clash of the heavy dishes and the clang of the cash register bell, all combine into a roar that has come to be the unnoticed and everyday accompaniment to the busy man’s lunch.”

1897 “Mr. Pundt, today or tomorrow, will place a 20-pound pig in front frozen in a block of ice, and that is something brand new in these latitudes, and is quite a credit to his fine taste.”

1901 “From Maine to California, from Florida to Wisconsin, the same choice of food is offered, all cooked and served in the same way.”

1906 “One in twenty cooks and waiters may be counted upon as steady and worth while. The rest will come and go in any and all fashions.”

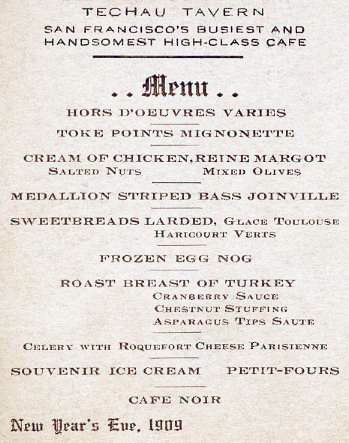

1909 “What sense is there in calling potatoes ‘Pommes de terre,” oysters ‘huitres,’ soups ‘potages,’ and so on through a lot of lingual fol-de-rol, when plain everyday English would tell the story comprehensively?”

1912 “Like all good things, it had imitators, and there have been no less than four Poodle Dogs and two Pups, each claiming to be a direct descendant of the original. Like ‘strictly fresh eggs,’ ‘fresh eggs’ and plain ‘eggs,’ we now have the Old Poodle Dog, the New Poodle Dog and the plain Poodle Dog.”

1912 “Like all good things, it had imitators, and there have been no less than four Poodle Dogs and two Pups, each claiming to be a direct descendant of the original. Like ‘strictly fresh eggs,’ ‘fresh eggs’ and plain ‘eggs,’ we now have the Old Poodle Dog, the New Poodle Dog and the plain Poodle Dog.”

1915 “It’s an age of standardization, and one restaurant is now much like every other, barring minor differences.”

1916 “It was a typical New York courtship. They visited restaurants of all degrees.”

1917 “At the present time, to quote Professor Ellwood, the modern family performs scarcely no industrial activities, except the preparation of food for immediate consumption, and even this activity with the advent of the bakery, cafeteria, café, and hotel seems about to disappear from the home.”

1920 “The men who patronize the cheaper restaurants look upon the waitress as a social equal and any man who comes in other than the rush hour expects a little visit with her.”

1920 “The men who patronize the cheaper restaurants look upon the waitress as a social equal and any man who comes in other than the rush hour expects a little visit with her.”

1922 “Places with old fashioned names and old fashioned furnishings should have waitresses in old fashioned costumes.”

1923 “A pronounced tendency of modern life is for people to eat out.”

1924 “All of the newcomers, the ‘Pig ‘n Whistles,’ the ‘Cat ‘n Fiddles,’ the ‘Lunchettes,’ the ‘Luncheonettes,’ the ‘Have-A-Bites’ and the What-Nots are now successfully bidding for the public favor.”

1927 “We serve the only real ‘Sho-nuff’ Down Home Plantation Dinner in Boston.”

1928 “Yet I have seen menus as tedious to read as a Theodore Dreiser novel. Beyond a certain number of well chosen dishes there is only distressing monotony.”

1929 “The little pink-curtained tea room that calls itself so disarmingly ‘Aunt Rosie’s Nook’ has bought its provisions on just such a system as Sing Sing employs.”

1932 “No lunch counter fails to add a leaf of lettuce to any sandwich that passes across the counter. No hotel or restaurant can do without lettuce. Lettuce is a habit.”

1934 “Cocktails at five o’clock used to be considered the privilege of the leisure class, but today in every white tile restaurant as well as the swankiest oasis men and women gather.”

1937 “The peculiarly American contributions to restaurant types are establishments meeting the demand for speed combined with economy: the cafeteria, automat, fountain lunch, sandwich shop and drug store counter.”

1937 “The peculiarly American contributions to restaurant types are establishments meeting the demand for speed combined with economy: the cafeteria, automat, fountain lunch, sandwich shop and drug store counter.”

1940 “I’m running a joint. It’s a good one, but it’s a road joint, started on a shoestring, called Kum Inn.”

1941 “A sure omen of a good tip is an order for scotch and soda before the meal.”

1941 “Tons and tons of Primex go into the frying kettles of The Flame each year. In fact, for eleven years this uniform quality fat has helped this famous Duluth restaurant build an enviable reputation for delicious fried foods.”

1941 “Tons and tons of Primex go into the frying kettles of The Flame each year. In fact, for eleven years this uniform quality fat has helped this famous Duluth restaurant build an enviable reputation for delicious fried foods.”

1943 “The days of ignoring lobster and hard to handle fish listed on restaurant menus are gone for the time being, and to help the perplexed diner we’ll list a few tips on tackling the denizens of the deep.”

1946 “Chromium may be all very well for an inexpensive place where your customers come for the most part from dull middle-class homes, so glitter and shine represent their escape.”

1951 “In whatever region he is traveling, the American tourist soon finds that good simple American cooking is an elusive myth.”

1952 “How to Do Simple Dish that Looks Fancy, Tastes Fancy and Costs Thirty-Eight Cents per Portion!”

1954 “Own Your Own Business – A Proven Investment – McDonald’s Speedee Hamburger – Franchises Available – A sensation in California and Arizona, showing profits well into 5 figures!”

1954 “Own Your Own Business – A Proven Investment – McDonald’s Speedee Hamburger – Franchises Available – A sensation in California and Arizona, showing profits well into 5 figures!”

1957 “Would you believe that in old Boston you could be transported to a native Polynesian Village surrounded by the lush, beautiful and exotic atmosphere of the South Pacific?”

1959 “The much maligned cocktail has kept many a restaurant solvent.”

1959 “The much maligned cocktail has kept many a restaurant solvent.”

1960 “The Ark was built here in Wilmington in 1922 and has served as an army troop transport, a banana boat, a gambling boat and as a coast guard quarter boat until purchased by Eldridge Fergus in 1951 and converted into a floating restaurant.”

1961 “At present, the amount of space needed for rough food preparation is smaller than before, while the area needed for frozen and dry foods must be larger. This is the result of the growing popularity among restaurant owners of pre-portioned and frozen food.”

1963 “Tad’s plush decor offsets any machine-like atmosphere. Red velour wall coverings and globe lighting creates an 1890s setting for a 1970 operation.”

1966 “Historic decor, the chef who cooks his steaks on a bed spring or an anvil, and the place where ‘famous people dine there’ all offer that ‘something extra’ a man needs to draw him out.”

1967 “When you enter the Buckingham Inn it’s like stepping into a charming old English Inn. There’s a feeling that you have stepped into one of the inns from the Canterbury tales that you read about in childhood.”

1968 “There is nothing complicated about roast beef. Its relatively high cost can be offset not only by volume sales, plus volume beverage sales, but by the ease with which employees can be trained to produce and serve roast beef.”

1970 “The Grand is an old-fashioned, slightly grubby, mildly tumultuous restaurant, but nonetheless pleasant. The food is often heavy, the waiters on the ancient side, the furnishings worn; but you come away with the feeling that you got your money’s worth and your day has been enhanced.”

1973 “Pre-prepared frozen beef slices, chunks or tips may be transformed into a variety of nationality dishes, such as Russian, Italian, Mexican, Hungarian and Oriental.”

1976 “Journey to prehistoric days via the stone-age decor and hearty feasting on Unique Appetizers, Fresh Seafood, Steaks, Barbeque Ribs; all complimented by an elegant Silver Salad Bar.”

1978 “A new definition of fresh must take into account that the potato salad, coleslaw or chicken salad you were served at lunch may have been more than a month old.”

1980 “In an adjective count we made from about 100 menus, by far the most common items were hot and fresh, with fresh considerably in the lead.”

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.