Recently the online reservations service OpenTable.com announced that their reservations for solo diners had gone up 62% over the past two years. Just how meaningful this increase was is hard to judge from so little information, but the press release conjectured that “the stigma surrounding dining solo may be starting to lift and . . . consumers are eager to savor unique culinary experiences alone.”

Recently the online reservations service OpenTable.com announced that their reservations for solo diners had gone up 62% over the past two years. Just how meaningful this increase was is hard to judge from so little information, but the press release conjectured that “the stigma surrounding dining solo may be starting to lift and . . . consumers are eager to savor unique culinary experiences alone.”

I can’t say with certainty that no one ever felt the stigma of eating alone in the 19th century but I believe that certain patrons were eager to savor any and all culinary experiences alone.

Why? In the early 19th century communal dining was the norm and there was little sense of privacy in public halls and dining rooms. An Englishman wrote in 1843 of his visit to America where he often felt he was “a fraction . . . of a huge masticating monster” as he dined “with people to whom he is bound by no tie but that of temporary necessity, and with whom, except the immediate impulse of brutal appetite, he has probably nothing in common.” An escape from the crowd was desirable to those who could afford to pay the price for a private dining room.

Stigma came later. It was the development of the luxury restaurant after the Civil War that created problems for the solo diner. Now there were no communal tables. Every table was private and the assumption was that no one dined alone. Portions were meant for two, so patrons made sure to arrive with a dinner companion. An article in the New York Sun in 1890 reported that this practice was so well known that “if a man comes in alone the waiters at once conclude that he is a countryman or unused to restaurant life, and treat him accordingly.”

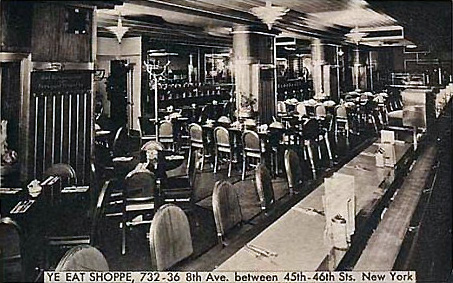

By contrast it was true then and has been since that in casual and self-service eateries where meals are quick and unceremonious – such as lunchcounters, diners, and fast food outlets – patrons typically eat alone entirely free of stigma or self-consciousness.

The history of dining alone has been a different story for women than for men, both in the 19th century and through most of the 20th. Until 1910 or so, the meaning of a phrase such as the following 1894 New York Herald headline “Lone Women Not Wanted [in First Class Restaurants]” is ambiguous. Usually what was meant by a “lone woman” was a woman unaccompanied by a man. Thus “lone women” could apply to a woman totally alone or several women together. None would be admitted to a fine restaurant.

Men often felt lonely eating by themselves in a restaurant, or that they were being treated as second class customers, but they were not turned away under suspicion of being prostitutes. The idea that a lone woman entering a restaurant might be in the sex trade was the reason given for barring her from first-class restaurants in the evening. Generally in the early 20th century fine restaurants and hotels in NYC reversed their policy, stating they would serve any lone woman they judged to be a “lady.” Yet, even as late as the 1960s, some restaurants would not seat a solitary woman at the bar for fear she was soliciting.

Even as it became more common and acceptable for women to dine alone, they continued to feel unwelcome even into the 1970s. In that decade, when more women had careers in which they traveled for business, they began to protest publicly about the difficulties they had in restaurants. Like men, they complained that they were given poor service, often ignored, or seated by the restrooms.

There are pragmatic reasons why restaurants have been less than thrilled about single diners. They occupy tables that could accommodate more guests, thus ordering less food and usually fewer drinks and producing lower tips. And lone diners have been painted as social rejects. Ann Landers wrote in 1962 that men eating alone had character flaws. It has even been suggested that solitary diners depress other diners. According to a 1976 columnist, a lone woman in particular “suggests disappointment, a failed rendezvous, an empty heart; she subtly alters the ambience of the restaurant like the scent of old pressed roses.”

There are pragmatic reasons why restaurants have been less than thrilled about single diners. They occupy tables that could accommodate more guests, thus ordering less food and usually fewer drinks and producing lower tips. And lone diners have been painted as social rejects. Ann Landers wrote in 1962 that men eating alone had character flaws. It has even been suggested that solitary diners depress other diners. According to a 1976 columnist, a lone woman in particular “suggests disappointment, a failed rendezvous, an empty heart; she subtly alters the ambience of the restaurant like the scent of old pressed roses.”

Little wonder that a survey in 1979 reported that most women found gynecological exams more pleasant than eating alone in a restaurant.

Just as there have always been some people who prefer eating alone, there have always been some restaurants that advertise special attention paid to lone diners. Lord & Taylor’s Birdcage in Westchester NY provided tables for one [pictured, 1950]. In the 1980s many restaurants stepped up their efforts. Even though 1980 Gallup survey interviews showed that 71% of men and 66% of women said they would rather not be seated at a table with other diners, a number of restaurants in the 1980s created communal tables. As far as I know it did not become a big trend. On the other hand, dining clubs such as “Fine Diners over 40″ in NYC may prove more appealing.

Just as there have always been some people who prefer eating alone, there have always been some restaurants that advertise special attention paid to lone diners. Lord & Taylor’s Birdcage in Westchester NY provided tables for one [pictured, 1950]. In the 1980s many restaurants stepped up their efforts. Even though 1980 Gallup survey interviews showed that 71% of men and 66% of women said they would rather not be seated at a table with other diners, a number of restaurants in the 1980s created communal tables. As far as I know it did not become a big trend. On the other hand, dining clubs such as “Fine Diners over 40″ in NYC may prove more appealing.

© Jan Whitaker, 2015

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.