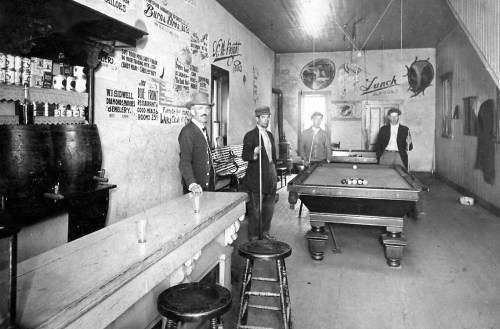

There are a lot of reasons why a restaurant might choose not to sell liquor that have nothing to do with religious beliefs. But restaurants that brand themselves as Christian absolutely never serve alcoholic drinks. This has always been their defining characteristic.

There are a lot of reasons why a restaurant might choose not to sell liquor that have nothing to do with religious beliefs. But restaurants that brand themselves as Christian absolutely never serve alcoholic drinks. This has always been their defining characteristic.

In the U.S. Christian invariably means Protestant. Catholics, though doctrinal Christians, don’t consider drinking alcohol sinful, nor does its avoidance confer holiness.

Although their predecessors date back to the 1870s when white Protestant women and men fought saloons by creating inexpensive, alcohol-free lunch rooms for low-income working men, Christian restaurants made their more recent return in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Some contemporary examples do not make a big display of their orientation. The Western burger chain In-N-Out, for example, prints a small biblical reference on the bottom of its soft drink cups that many customers probably never notice. The Atlanta-based Chick-fil-A chain has a religious mission statement and is closed on Sundays; but its religiosity was not known to all until a few years back when its late founder declared support for conservative family values.

Although their predecessors date back to the 1870s when white Protestant women and men fought saloons by creating inexpensive, alcohol-free lunch rooms for low-income working men, Christian restaurants made their more recent return in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Some contemporary examples do not make a big display of their orientation. The Western burger chain In-N-Out, for example, prints a small biblical reference on the bottom of its soft drink cups that many customers probably never notice. The Atlanta-based Chick-fil-A chain has a religious mission statement and is closed on Sundays; but its religiosity was not known to all until a few years back when its late founder declared support for conservative family values.

Other common characteristics of Christian restaurants have included banning smoking and, like Chic-fil-A, closing on Sundays. Most have made an effort to offer some kind of ministry, ranging from offering religious pamphlets to preaching or providing live or recorded gospel music. Some have made free meals available for the poor. Typically they have had “biblical” names such as The Fatted Calf, The Ark, or The Living Bread. In some cases, the staff has been asked to assemble for daily prayers. Proprietors tend to be deeply religious, some having been redeemed from a troubled past. And, finally and not surprisingly, many (but not all) have been located in the “bible belt” where evangelistic religion thrives.

Other common characteristics of Christian restaurants have included banning smoking and, like Chic-fil-A, closing on Sundays. Most have made an effort to offer some kind of ministry, ranging from offering religious pamphlets to preaching or providing live or recorded gospel music. Some have made free meals available for the poor. Typically they have had “biblical” names such as The Fatted Calf, The Ark, or The Living Bread. In some cases, the staff has been asked to assemble for daily prayers. Proprietors tend to be deeply religious, some having been redeemed from a troubled past. And, finally and not surprisingly, many (but not all) have been located in the “bible belt” where evangelistic religion thrives.

Some Christian restaurants went a little bit further. The Praise The Lord Cafeteria in Cleveland TN was unusual for a cafeteria in that it featured gospel singing, preaching, and testifying on weekend evenings. Waitresses at Seattle’s Sternwheeler often greeted customers with “Praise the Lord.” The owner of Heralds Supper Club in 1970s Minneapolis MN grilled prospective singers until he was convinced that they were genuine Christians. The owners of the Fatted Calf Steak House in Valley View TX, whose specialty was a 24-ounce T-bone, were more trusting: they let patrons pay whatever they could and even allowed them to remove money from the payment jar if they were in need. But the honor system was strenuously abused and the restaurant closed in heavy debt after just 1½ years.

I became interested in this phenomenon when I noticed that a postcard in my collection – the Kozy Country Kitchen in Kingsville OH — said on the back, “Family dining in A Christian Atmosphere.” As shown on the card, it’s a highway restaurant with a big sign and parking lot looking as though it serves truckers, and was not the kind of place that would be likely to offer beer, wine, or cocktails even if it was run by licentious pagans. So what, I wondered, made its atmosphere Christian?

I became interested in this phenomenon when I noticed that a postcard in my collection – the Kozy Country Kitchen in Kingsville OH — said on the back, “Family dining in A Christian Atmosphere.” As shown on the card, it’s a highway restaurant with a big sign and parking lot looking as though it serves truckers, and was not the kind of place that would be likely to offer beer, wine, or cocktails even if it was run by licentious pagans. So what, I wondered, made its atmosphere Christian?

Now that I’ve done some research I think I know the answer. It was probably an overtly friendly place, but one that frowned on swearing or arguing. Maybe it was similar to Hayble’s Hearth Restaurant in Greensboro NC. Hayble’s was very successful compared to most Christian restaurants, staying in business for nearly 20 years. In 1975 its manager said that she found Hayble’s a nice place to work because, “There’s no fightin,’ no fussin,’ no cussin.’” This made me realize that not everyone’s experiences with restaurants are like my own in which the norm is a focus on food and socializing, with moderate drinking in a cordial atmosphere.

Now that I’ve done some research I think I know the answer. It was probably an overtly friendly place, but one that frowned on swearing or arguing. Maybe it was similar to Hayble’s Hearth Restaurant in Greensboro NC. Hayble’s was very successful compared to most Christian restaurants, staying in business for nearly 20 years. In 1975 its manager said that she found Hayble’s a nice place to work because, “There’s no fightin,’ no fussin,’ no cussin.’” This made me realize that not everyone’s experiences with restaurants are like my own in which the norm is a focus on food and socializing, with moderate drinking in a cordial atmosphere.

A special type of Christian restaurant developed out of the more-urban Christian coffeehouse movement that had been aimed at a teenaged clientele. It was the Christian supper club which served a buffet-style dinner followed by a show featuring singing groups performing gospel hymns. Some were run under church sponsorship, but many were commercial ventures. The first was the Crossroads Supper Club organized as a non-profit in Detroit in 1962 by an association of churches and businessmen. Its manager, who had formerly worked as an assistant to Billy Graham, said it was called a supper club because “night club” had unsavory connotations. Its initial success inspired a Methodist minister associated with Crossroads to suggest that one day there might be a “Pray-Boy Club” whose members held keys to individual chapels. (He was joking, wasn’t he?) However, like many Christian restaurants and supper clubs, Crossroads soon fell on dark days.

The heyday of the Christian supper club was in the late 1970s and 1980s. By the 1990s it was fading. One of the more ambitious-sounding ventures was Gloryland in Hot Springs AR. The project rallied investors to transform a former nightclub called The Vapors — famed for being colorful in a non-Christian way — into a supper club. Slated to open in 1991, the venture never got off the ground.

The heyday of the Christian supper club was in the late 1970s and 1980s. By the 1990s it was fading. One of the more ambitious-sounding ventures was Gloryland in Hot Springs AR. The project rallied investors to transform a former nightclub called The Vapors — famed for being colorful in a non-Christian way — into a supper club. Slated to open in 1991, the venture never got off the ground.

Undoubtedly the most successful of the Christian supper clubs, the one that served as a model for others, was The Joyful Noise, with two locations in the Atlanta GA metropolitan area. The first was financed with contributions from 500 stockholders who, according to president Bill Flurry, wanted “clean entertainment” in a place without smoking or drinking. The Joyful Noise(s) enjoyed about 20 years in business, from 1974 to 1994.

© Jan Whitaker, 2017

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.