Although “gypsy” tea rooms could be found in the 1920s, and occasionally even now, their heyday was in the 1930s Depression.

Although “gypsy” tea rooms could be found in the 1920s, and occasionally even now, their heyday was in the 1930s Depression.

They represented a degree of degeneration of the tea room concept in that they built their allure on tea leaf reading as much as – or more than — food. The menus in some of them consisted simply of a sandwich, piece of cake, and cup of tea, typically costing 50 cents. A drug store in New Orleans reduced the menu to a toasted sandwich and tea for the low price of 15 cents.

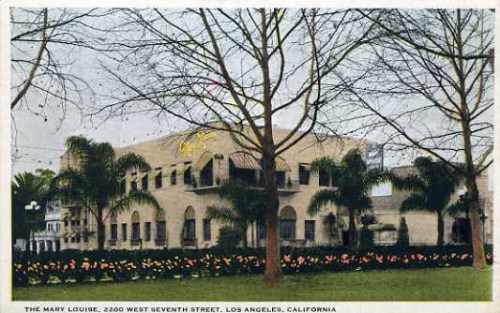

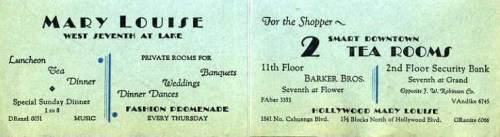

Gypsy tea rooms were often located on the second or third floor of a building, reducing the rent burden. Downtown shopping districts were popular places to attract customers, with about twenty near NYC stores located in the 30s between 6th and 7th Avenues. Los Angeles had a Gypsy Tea Room across the street from Bullock’s department store, while Omaha’s Gypsy Tea Shop, affiliated with another one in Council Bluffs IA, was across from the Brandeis store.

Times were hard, and Gypsy, Mystic, or Egyptian tea rooms, as they were known, offered a diversion from the concerns of the day and a way to prop up tottering businesses.

Usually it was all in fun. Gypsy tea rooms dressed waitresses in peasant costumes with bandana headdresses and adopted brilliant color schemes such as orange and black with yellow candles, and red tables and chairs. Such decor was a formula worked out by a New York City woman who by 1930 had opened 25 such places all over the country. Evidently after opening each one she sold it to a new owner.

Usually it was all in fun. Gypsy tea rooms dressed waitresses in peasant costumes with bandana headdresses and adopted brilliant color schemes such as orange and black with yellow candles, and red tables and chairs. Such decor was a formula worked out by a New York City woman who by 1930 had opened 25 such places all over the country. Evidently after opening each one she sold it to a new owner.

Most customers, almost always women, saw the readings as light entertainment suitable for clubs and parties. Sometimes, though, an advertisement suggested that patrons’ reasons for having their tea leaves read were not so happy. A 1930 advertisement for the Mystic Tea Room, in Kansas City MO, asked “Have You Worries? Financial, domestic or otherwise? Our gifted readers will help you solve your problems.”

Many tea leaf readers had names suggesting they were “real gypsies” but that is unlikely, despite the Madame Zitas, Estellas, and Levestas. In fact, the reason that tea rooms advertised free readings was because many states and cities had laws prohibiting payment for fortune telling so as to keep genuine gypsies from settling there. A Texas law of 1909 declared “all companies of Gypsies” who supported themselves by telling fortunes would be punished as vagrants.

Many tea leaf readers had names suggesting they were “real gypsies” but that is unlikely, despite the Madame Zitas, Estellas, and Levestas. In fact, the reason that tea rooms advertised free readings was because many states and cities had laws prohibiting payment for fortune telling so as to keep genuine gypsies from settling there. A Texas law of 1909 declared “all companies of Gypsies” who supported themselves by telling fortunes would be punished as vagrants.

New York state passed a law in 1917 that made fortune telling in New York City illegal. In the 1930s police conducted raids of tea rooms advertising tea leaf readings. The raids did little to reduce their ranks and tea rooms continued to announce readings. A “gypsy princess” on site was an undeniable attraction — “Something New, Something Different,” according to an advertisement for Harlem’s Flamingo Grill and Tea Room on 7th Avenue.

In 1936 an attempt was made to organize tea leaf readers but it didn’t seem to amount to much. Members of the National Association of Fortune Tellers were required to be “scientific predictors,” just as good at forecasting as Wall Street brokers. The group’s organizer said she wanted to professionalize fortune telling. Because 32 states had laws against it, she said, tea room readers were forced to work for tips only, to the benefit of tea room owners.

Tea leaf readers seemed to move around quite a bit, perhaps because tea room proprietors wanted to keep things interesting. It was supposed to generate excitement when a “seer” from abroad or a larger city visited a small town tea room. A male clairvoyant such as Pandit Acharjya of Benares, India, was bound to enliven the atmosphere at the Gypsy Tea Room in New Orleans in 1930. And to the River Lane Gardens in Jefferson City MO, even the week-long appearance of “Miss Ann Brim of St. Louis, Famous Reader of Cards and Tea Leaves” was worth billing as a major attraction.

Tea leaf readers seemed to move around quite a bit, perhaps because tea room proprietors wanted to keep things interesting. It was supposed to generate excitement when a “seer” from abroad or a larger city visited a small town tea room. A male clairvoyant such as Pandit Acharjya of Benares, India, was bound to enliven the atmosphere at the Gypsy Tea Room in New Orleans in 1930. And to the River Lane Gardens in Jefferson City MO, even the week-long appearance of “Miss Ann Brim of St. Louis, Famous Reader of Cards and Tea Leaves” was worth billing as a major attraction.

In Boston, the Tremont Tea Room has been doing business in sandwiches and tea leaf readings since 1936. Proving, as if proof is needed, that no “restaurant” concept ever totally dies away.

© Jan Whitaker, 2017

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.