A veil of ominous mystery has spread over the remains of a California roadside tea room once known by the homey name Singing Kettle.

A veil of ominous mystery has spread over the remains of a California roadside tea room once known by the homey name Singing Kettle.

It was located near the summit of Turnbull Canyon, high above the San Gabriel Valley, on a winding road running through the Puente Hills in North Whittier. The road was completed in 1915, opening up a route filled with what many regarded as the most impressive views on the entire Pacific Coast.

Today young people drive into the “haunted” canyon at night determined to be frightened to death. Gazing out car windows they eagerly tell each other tales they’ve heard of satanic rituals, murders, and human sacrifice, hoping that behind that fence are unspeakable horrors they might be lucky enough to witness. Even the Singing Kettle tea room, perhaps because remnants of its entrance are visible from the road, has become enmeshed in dark fantasies.

Why am I laughing?

Because it strikes me as funny that a tea room from the 1920s and 1930s could be associated with horror and paranormal events. Or even that people would find its existence mysterious, wondering why it was ever there or what it really was.

I suppose that given enough time and imagination mysterious auras can envelop any mundane place, even a deserted mall or a parking garage. But still, finding a tea room scary is like being frightened by a club sandwich.

I have experienced a somewhat similar attitude before. I gave a talk on tea rooms of New York City when my book Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn came out in 2002. Afterwards a man in the audience came up and asked me why I didn’t mention the darker aspects of tea rooms. He was fixated on the idea that a lot of them had been speakeasies and houses of prostitution.

Really? If that had indeed been the case, why would I not have mentioned it? It would be a good story. I’ve found little evidence of prostitution in tea rooms. It’s true that some, a minority, of tea room proprietors were found selling liquor during Prohibition. A few places in Greenwich Village were raided in the early 1920s, and here and there the mob would open a joint and call it a tea room, though that was purely a ruse. They were totally fake. I feel certain it was impossible to order a diet plate or a Waldorf salad in a mob tea room.

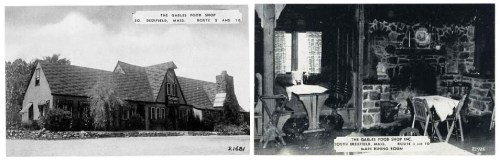

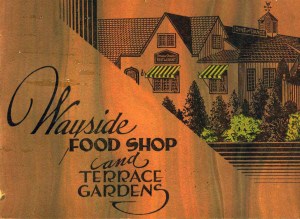

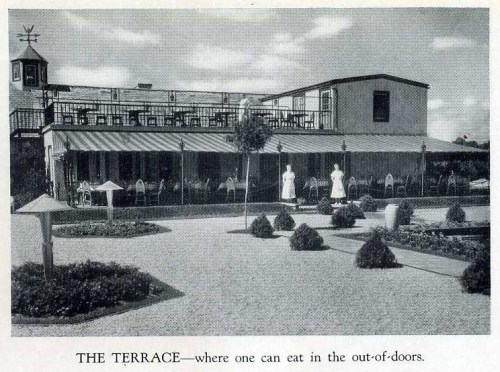

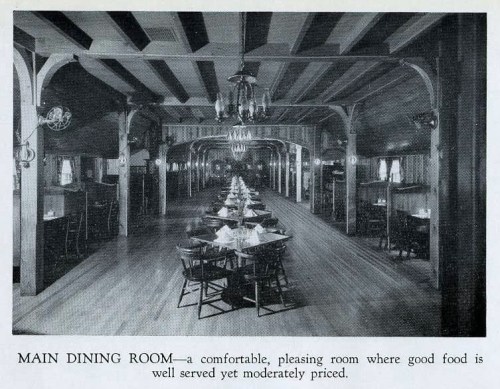

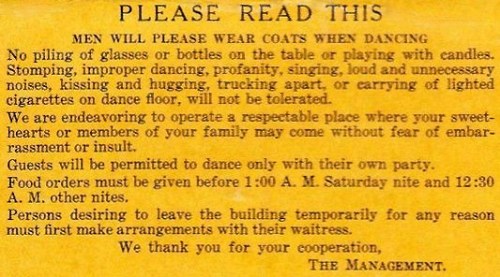

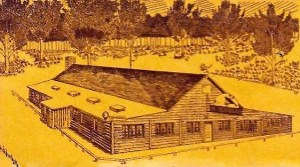

The dining area of the Singing Kettle tea room was up the hill from the pergola entrance shown on the black and white postcard above. As can be seen from a bird’s-eye view of the property, terraced stairs with fountains and shrubbery led up to the main tea room which today appears to be a residence. The view while dining would have been spectacular.

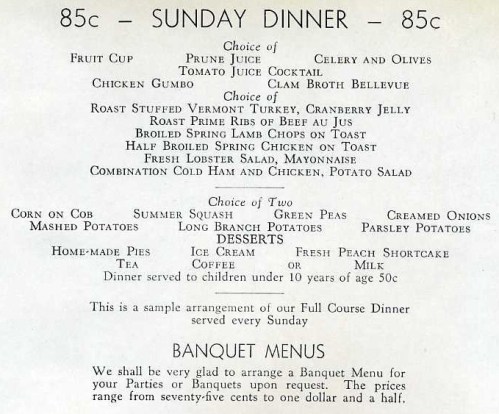

The tea room was frequented by students and staff from Whittier College, the Whittier Chamber of Commerce, and women’s clubs. It was a popular place for business meetings, card parties, wedding receptions, and bridal showers. Weddings were held in the inner courtyard of its entrance pergola.

I have not been able to discover exactly who ran the Singing Kettle. It was said to be owned and operated by a major Southern California agricultural land developer, Edwin G. Hart, but I can’t establish if he was headquartered on the property or was directly involved in the business. He did promote the tea room in a 1927 advertisement for his new residential development, Whittier Heights.

I have not been able to discover exactly who ran the Singing Kettle. It was said to be owned and operated by a major Southern California agricultural land developer, Edwin G. Hart, but I can’t establish if he was headquartered on the property or was directly involved in the business. He did promote the tea room in a 1927 advertisement for his new residential development, Whittier Heights.

The Singing Kettle was in business from 1926 until at least 1939, but probably not much longer. It surely would not have survived gasoline rationing during WWII.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

With many thanks to the reader who told me about the Singing Kettle.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.