Famous, but also infamous in its day because of how it portrayed the South before the Civil War and Emancipation as a world of smiling slaves who loved serving the kindly white people who held them captive.

Beyond its costumed mammy servers and the Black children who boisterously recited the menu, sang, danced, and proclaimed the South would rise again, the proprietors of Aunt Fanny’s Cabin restaurant in Smyrna GA created a legend regarding its name and building which appropriated and falsified the life story of a living woman.

According to an oft-told tale, the restaurant’s core building was a relic of the Civil War era and the home of a former slave, Fanny Williams, who spent her last years sitting on the restaurant’s front porch telling of the war and its aftermath. At her death in 1949 legend had it that she was very old, her age ranging from somewhere in the 90s to much older. She was “about 112 years old” when she died, restaurant owner George Poole told a reporter in 1982.

Indeed there was a real Afro-American woman named Fanny Williams. However it was revealed after the restaurant closed in the 1990s that she was born after the Civil War and had never lived in the cabin, which itself dated from the 1890s. Poole’s estimate of her 112 years had been preposterous – only a few dozen people worldwide were known to have attained that age — but newspapers had been much inclined to lax reporting when it came to Aunt Fanny’s Cabin. Far from an ancient rural yokel, she was about 81 when she died, a city dweller in Atlanta, and active in raising funds for her church there. How willingly or why she adopted the ex-slave persona is unknown.

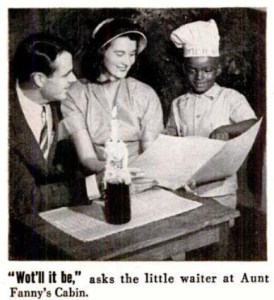

Fanny Williams was a servant to a wealthy Atlanta family named Campbell. She was in service to socialite Isoline Campbell McKenna in 1941 when McKenna opened a tea room-style eating place on family property near their summer home. She named it Aunt Fanny’s Cabin, hosting ladies’ luncheons, bridge clubs, and bridal showers. She leased the business in 1947, selling it to lessees Harvey Hester [pictured above instructing his employees] and Marjorie Bowman in 1954. They elaborated the Aunt Fanny legend, enacted in what are known as “Blacks in Blackface” scenes where cheerful servers sang, danced, and even joined patrons in singing “Dixie,” the anthem of the ante-bellum South. According to a newspaper report in 1977 the restaurant’s decor included framed advertisements for slaves.

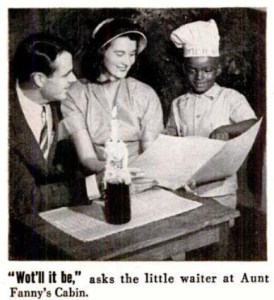

The restaurant’s third owner, George “Pongo” Poole, continued the song and dance tradition into the 1980s, although when a cabaret tax was demanded, dancing by the Black boys stopped. However, they continued to carry yoke-style wooden menu boards around their necks while they shouted out the menu offerings [child waiter shown below in 1949 before the menu boards were used].

The restaurant drew Georgians from Smyrna and Atlanta, as well as visitors from all over the country and the world. It was a tour bus stop, and a favorite of President Jimmy Carter and conventioneers such as members of the American Bar Association. Those who complained about the roles played by Black servers and the implicit celebration of slavery were characterized by proprietors as “Northern liberals,” though there is evidence that some Southerners and Westerners were also critical.

It became standard procedure when reporting on the restaurant to quote Poole about how his staff loved working there and was part of a big happy family. When interviewed, Black women servers would invariably attest to their love of the job and how they never felt insulted. To what extent this was a genuine expression on their parts is unknown.

It became standard procedure when reporting on the restaurant to quote Poole about how his staff loved working there and was part of a big happy family. When interviewed, Black women servers would invariably attest to their love of the job and how they never felt insulted. To what extent this was a genuine expression on their parts is unknown.

What is known is that many of the elements that characterized the restaurant had been subjects of contention for a long time. A 1964 survey by Wayne State University researchers showed that most Black respondents found terms such as Sambo, Aunt Jemima, auntie, mammy, spook, and darkie offensive. Many white people, especially in the South, did not understand this, and thought that calling an elderly Black man or woman Uncle or Aunt/ie was a mark of respect. As for “mammy,” despite the affection many Southerners felt for the Black women who had cared for them when they were children, it had been rejected by many Americans long before the 1960s. In the 1920s the National Organization of Colored Women’s Clubs mobilized massive opposition to a Washington, D.C. memorial to mammies proposed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. “One generation held the black mammy in abject slavery; the next would erect a monument to her fidelity,” said the club women’s official statement in 1923.

Georgia Senator Julian Bond said in the 1980s that he had little attraction to Aunt Fanny’s Cabin but could imagine that younger Blacks might find it “cute.” A journalist with the Atlanta Constitution who visited the restaurant in 1984 reported that he saw numerous Black patrons.

So, what’s the story? Did the degree of tolerance or even liking that some Black people expressed for Aunt Fanny’s Cabin mean that it held no offense to people of color? Did it mean that those who complained were thin-skinned trouble makers with an elevated sense of their own dignity who couldn’t take a joke? Did it mean, as a 1982 Washington Post story argued, that the years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were part of a post-racial age in which slavery, forced segregation, and lynching had largely ended and any remaining blatant prejudice was due simply to a few “obnoxious rednecks”?

I think not.

I think not.

I cannot be absolutely certain that there has never been a Black-owned restaurant that celebrated plantations, “pickaninnies,” and “mammies” of the Old South, but all the mammy restaurants I know of, mostly in business from the 1930s to the Civil Rights era of the 1960s, were white-owned. And dressing Black women servers in mammy get-ups was so commonplace back then that at times I’ve wondered if wearing that costume was a waitressing job requirement for dark-skinned women.

After the death of owner George Poole, Aunt Fanny’s Cabin struggled and subsequent owners could not revive it. It closed for the last time in 1994, sometimes recalled as partly a victim of “political correctness.” Based on the understanding that the original portion of the restaurant’s building had been a slave cabin, the city of Smyrna proposed to move it downtown to be used as a visitors’ center. After a historic structures report revealed it dated from the 1890s, the city decided to go ahead with the project on the grounds that the restaurant had itself been a significant part of the city’s history.

© Jan Whitaker, 2016

Update regarding comments: From now on I will approve only thoughtful comments that address the theme of this blog post which is the restaurant’s portrayal of history and how that shaped the roles available to Black staff. I will not approve comments that assert that everyone loved working there or that rave about the fried chicken. I have already held some back for these reasons — along with some hate comments — but now it is my policy. March 5, 2021

December 16, 2021 update: The remaining Aunt Fanny’s Cabin is going to be torn down! Thanks to “MadamC” for sending this link to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution story.

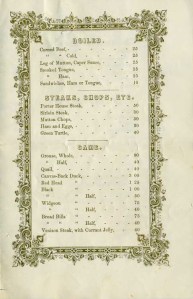

I counted at least 27 main dishes on a 1984 Pyramid menu, suggesting that the restaurant must have had a mighty big freezer. Along with beef, chicken, and seafood specials was the puzzler, “Spearamid – on bed of rice.” Slowly it dawned on me that the word rhymed with pyramid, and was their coining. I then discovered it was beef, onion, peppers, and tomatoes grilled on a skewer.

I counted at least 27 main dishes on a 1984 Pyramid menu, suggesting that the restaurant must have had a mighty big freezer. Along with beef, chicken, and seafood specials was the puzzler, “Spearamid – on bed of rice.” Slowly it dawned on me that the word rhymed with pyramid, and was their coining. I then discovered it was beef, onion, peppers, and tomatoes grilled on a skewer.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.