Every month in 1966 – 55 years ago — the Gallup organization surveyed about 1,600 Americans to find out what they thought about restaurants. The surveys were conducted for and published in Food Service Magazine.

Then, as now, dining out took place at a time of upheaval. It was a year of turmoil, with the U.S. bombing Hanoi as the Vietnam war raged on and protestors spilling into the streets. Black Americans pushed civil rights to the forefront, often meeting resistance from whites.

Gas cost 32 cents a gallon. The minimum wage was stuck at $1.25 despite attempts to raise it. Gallup divided the population into five income categories, with yearly family income under $3,000 at the bottom, and $10,000 and over at the top.

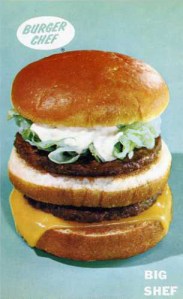

The restaurant industry was growing rapidly, led by lower-priced chains such as Denny’s, McDonald’s, and Jack in the Box. According to the National Restaurant Association, by 1966 annual restaurant volume had grown to $20 billion, compared to about $3 billion in 1940.

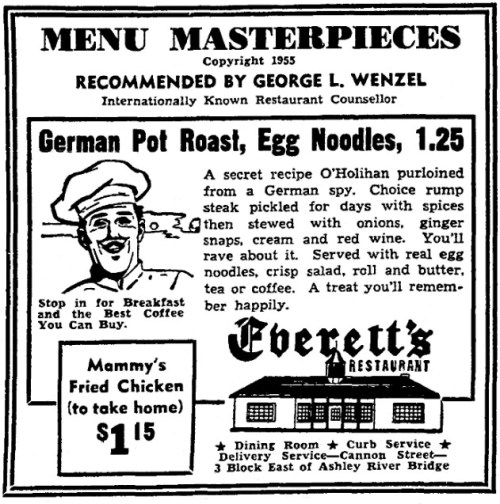

That year a steak dinner at a Bonanza Steak House came to $1.39. Very much at the opposite pole was Voisin in New York City where a dinner of Foie Gras, Consommé, English Sole, Squab Chicken, Fresh Peas and Asparagus, finished with Almond Soufflé, accompanied by wine, would come to $25 plus tip. Of course most restaurant meals were priced much closer to Bonanza’s then.

What did Americans want in a restaurant? The loudest and clearest message received by Gallup’s pollsters was that restaurant goers valued cleanliness more than atmosphere or appearance and almost as much as good food. “If there is anything Americans want, it is a restaurant that is clean, clean, clean!” the January report exclaimed. Diners had an eagle eye for sticky menus, flatware with water marks, waitresses with grimy fingernails, and dirty rags for wiping tables.

The most common answer to why eat out? was to have a change in routine, an attraction in itself far more appealing than getting a special kind of food, such as “Italian, Chinese, seafood, etc.” At a time when (white) married women were supposed to shun employment, it was hardly surprising that many commented that they wanted relief from cooking or just to get out of the house.

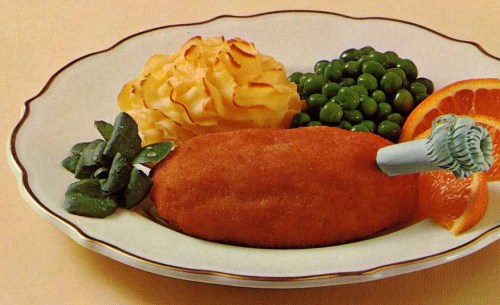

It is especially interesting that it seemed as if not all Americans had been won over to frequent restaurant meals. Pollsters were surprised to learn that many respondents actually preferred home cooking to restaurant food. The report noted that “many patrons really look down their noses at restaurant-prepared hamburger, roast beef, fish, chicken, baked potato and soup.” Grasping for an explanation, it asked: “Is the apparent preference for home cooking really a protest against the drab presentation of food in so many restaurants . . .?”

I find it somewhat surprising that the 1966 Gallup reports as published by Food Service Magazine candidly expressed criticisms of American restaurants. Another area they identified as in need of improvement was the lack of atmosphere. They noted: “Too many American restaurants have no personality – offer nothing that will give patrons a sense of participating in the exciting adventure that eating out really ought to be.”

But looking at the twelve monthly survey reports of 1966, I wonder just how much excitement in dining Americans actually wanted. According to the survey focused on atmosphere, the characteristic liked best about respondents’ favorite restaurant was “pleasant atmosphere,” (42%) followed by cleanliness (40%). Unsolicited comments referred to positive attributes such as “good-looking waitress,” “not too dark [lighting],” and “they leave me alone once I have been served.”

Clearly patrons weren’t looking for adventures in dining or in food. When asked “If you were going out to dinner tonight, which two of the foods on this list would you most likely select to go with your favorite meat dish?” most preferred baked potatoes and green beans. As for appetizers, 55% of respondents chose tomato juice as their favorite, although those with incomes over $10,000 preferred shrimp cocktail.

A short article prepared as part of a 12-page newspaper insert on the occasion of the 1966 opening of a new Forum Cafeteria in Miami remarked about the restaurant’s music: “Music by Muzak was designed to be unobtrusive and require no active listening. It avoids distracting musical devices and has a uniquely distinctive character which never forces itself on the conscious minds of its audience.”

I wonder whether the average American restaurant of 1966 achieved the same effect in dining.

© Jan Whitaker, 2021

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.