Ethnic restaurants are generally seen as places where people from cultures outside the U.S. provide meals similar to what they ate in their homelands. A high degree of continuity between restaurant owners, cooks, and cuisines is presumed, as in: the Chinese run Chinese restaurants in which Chinese cooks prepare Chinese dishes.

Questions are sometimes raised about whether, for example, Chinese restaurants in America have adapted to American consumer’s tastes to the point where the Chinese cuisine is not “authentic,” but few question how obviously true or historically accurate it is to assume that Chinese always cooked or served Chinese food.

History is rarely tidy. Chinese, Germans, and Italians cooked French food. Germans ran English chop houses. And people of almost all ethnicities — Irish, Italian, German, Croatian, Greek — cooked American food and owned American restaurants.

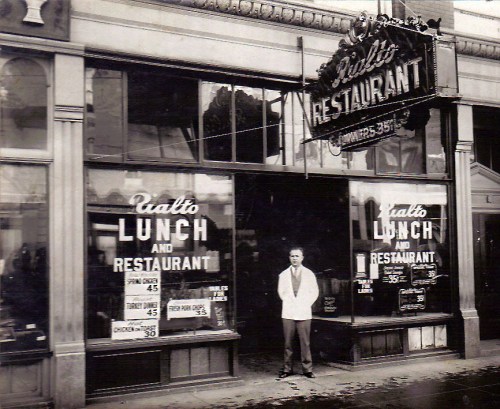

Greek immigrants, in fact, have been especially inclined to run American restaurants which serve mainstream American food, with little suggestion of the Mediterranean. Typically they’ve been the independent quick lunches, luncheonettes, coffee shops, and diners that are open long hours, serving breakfast, lunch, and dinner to working people. Many have been run under business names such as Ideal, Majestic, Elite, Cosmopolitan, Sanitary, Purity, or Candy Kitchen, rather than the proprietor’s name.

Greek immigrants, in fact, have been especially inclined to run American restaurants which serve mainstream American food, with little suggestion of the Mediterranean. Typically they’ve been the independent quick lunches, luncheonettes, coffee shops, and diners that are open long hours, serving breakfast, lunch, and dinner to working people. Many have been run under business names such as Ideal, Majestic, Elite, Cosmopolitan, Sanitary, Purity, or Candy Kitchen, rather than the proprietor’s name.

The emphasis on names suggesting quality or cleanliness is explained by the tendency of Americans in the early 20th century to brand Greek-run eateries as “greasy spoons” or “holes in the wall.” A negative attitude to Greek eating places is evident in the following piece of rhyme published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer in 1926 entitled “Where Greek Meets Greek”:

The other day I wandered in where angels fear to tread –

I mean the well known Greasy Spoon, where hungry gents are fed;

Where eats is eats and spuds is spuds, and ham is ham what am –

And the pork in the chicken salad is honest-to-goodness lamb.

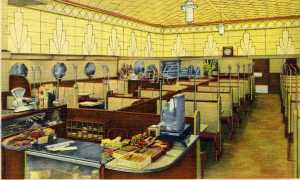

Certainly there were substandard Greek restaurants, but I’ve found that Greek-American proprietors had a propensity to plow profits into modern equipment and fixtures whenever possible.

Greek immigrants showed strong affinity with the restaurant business since the beginning of the 20th century when they began coming to the U.S. in large numbers. The reason for this is often attributed to a lack of English skills, but the first Greek restaurants, actually coffeehouses where patrons could linger, probably had more to do with the absence of women among early Greek migrants. Coffeehouses furnished community. Although in big Eastern cities many Greek restaurants continued to focus on Greek immigrants, many enterprising Greeks took the step of expanding beyond their compatriots. Some, such as Charles Charuhas who established the Washington, D.C. Puritan Dairy Lunch in 1906, were expanding or transitioning from the confectionery and fruit business.

While heavily invested in the New England lunch room business, especially in Providence RI and Lowell MA, Greek immigrants spread to many regions of the U.S, bringing restaurants to the restaurant-starved South. It is impressive that a Raleigh-based Greek trio opened its 15th restaurant in North Carolina as early as 1909. At that time, Greeks were said to be “invading” the lunch room trade in Chicago, operating about 400 places. Because of the simplicity of American cuisine, it was said that two months spent shadowing an American cook was all it took for Greek restaurateurs to pick up the necessary skills.

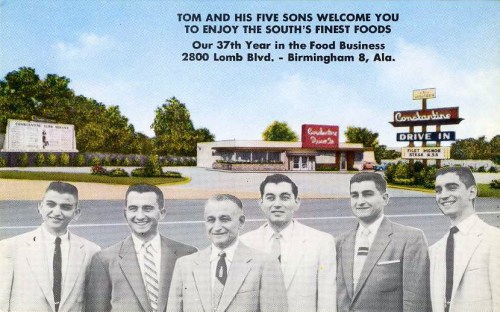

Other successful Greek restaurateurs of the past century included John Raklios who at one point owned a chain of a couple dozen lunch rooms in Chicago. In New York City Bernard G. Stavracos ran the first-class restaurant The Alps on West 58th, established in 1907. The Demos Cafe in Muskegon MI was one of that city’s leading establishments. In Dallas The Torch of the Acropolis (pictured) had a 36-year-long run, closing in 1984, while the College Candy Kitchen was an institution in Amherst MA.

Other successful Greek restaurateurs of the past century included John Raklios who at one point owned a chain of a couple dozen lunch rooms in Chicago. In New York City Bernard G. Stavracos ran the first-class restaurant The Alps on West 58th, established in 1907. The Demos Cafe in Muskegon MI was one of that city’s leading establishments. In Dallas The Torch of the Acropolis (pictured) had a 36-year-long run, closing in 1984, while the College Candy Kitchen was an institution in Amherst MA.

The children of successful Greek restaurant owners often preferred professional careers, but a new wave of Greek immigrants arrived after WWII, gravitating to diners, particularly it seems, in New Jersey. In 1989 the author of the book Greek Americans wrote that according to his estimate about 20% of the members of the National Restaurant Association had Greek surnames. And, as if demonstrating a flair for adaptation, according to a 1990 study, Greek-Americans were then dominating Connecticut’s pizza business.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.