You might imagine that chain restaurants would spend vast amounts of time and money researching potential names in order to pick one that would convey exactly the desired associations and nuances. Certainly one that would not insult a portion of its intended customers.

I’m sure most do. Sambo’s was not among them.

Wouldn’t the founders of Sambo’s, in the late 1950s, dimly perceive that the name Sambo was not beloved by everyone, especially African-Americans?

Why would they decorate with images from the book “Little Black Sambo,” the American editions of which were filled with racist caricatures?

Evidently they had no idea that Sambo had been – and still was – a derogatory word for black males for over 100 years; that the name and ridiculous images of Sambo were used on many consumer products in the early 20th century; and that after WWII school libraries had complied with requests by African-Americans to remove the book from shelves.

Even if they didn’t know any of this, when protests erupted they might have realized they had made a terrible mistake. Regardless of whether “Sam-bo” originated from the first name of one of them combined with the nickname of the other.

Nope, nope, nope, and double nope.

Instead the founders, their successor, and the corporation that finally took over the chain all insisted right up to the bitter end that no harm was intended or implied. Even as they renamed some units in the East where there had been boycotts, the company insisted the change was purely in order to market their new menus.

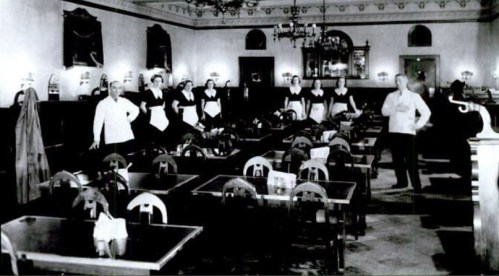

The first Sambo’s was opened in Santa Barbara in 1957. [pictured] By 1977, when the son of one of the founders was heading the company, the chain was the country’s largest full-service restaurant chain, with 1,117 units.

The first Sambo’s was opened in Santa Barbara in 1957. [pictured] By 1977, when the son of one of the founders was heading the company, the chain was the country’s largest full-service restaurant chain, with 1,117 units.

But trouble was looming. Protests during the West Coast chain’s expansion into the Northeast had already resulted in renaming units in the Albany NY area “Jolly Tiger.” Eventually there were 13 Jolly Tigers in various towns. Protest would spread to Reston VA, New York, and New England including at least 9 towns in Massachusetts. In 1981 the Rhode Island Commission on Human Rights ordered the company to change its name in that state because indirectly the name violated the 1964 Civil Rights Act by denying public accommodations to black persons.

The company responded that it would rename 18 of its Northeastern units “No Place Like Sam’s”; in fact according to an advertisement a few months later they actually renamed 41 units.

The company responded that it would rename 18 of its Northeastern units “No Place Like Sam’s”; in fact according to an advertisement a few months later they actually renamed 41 units.

Soon thereafter the company began to collapse. In November 1981 it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, closing more than a third of its units. In Leominster and Stoughton MA, early morning customers had to pick up and get out immediately so the restaurants could be padlocked.

In 1982 all, or most, remaining Sambo’s were renamed Seasons. By 1984 most of the Seasons restaurants had been sold to Godfather’s Pizza and other buyers.

The successive name switches undoubtedly hurt business, but a more serious problem was that Sambo’s, like other chains using a coffee shop format with table service and extensive menus, had been steadily losing out to fast food chains. Unsurprisingly, it did not survive.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

The more expensive restaurants were first to suffer from the area’s decline as well-dressed, well-heeled customers stopped coming. Conventioneers were warned off, in many cases, by cabdrivers who refused to drive there. Clubs with go-go dancers in the windows displaced coffeehouses with folksinging and poetry as a younger, more casually dressed crowd took over.

The more expensive restaurants were first to suffer from the area’s decline as well-dressed, well-heeled customers stopped coming. Conventioneers were warned off, in many cases, by cabdrivers who refused to drive there. Clubs with go-go dancers in the windows displaced coffeehouses with folksinging and poetry as a younger, more casually dressed crowd took over.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.