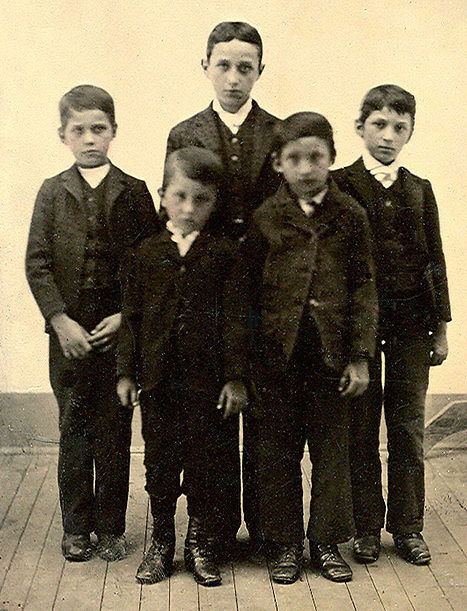

It’s rare to find business documents from long-gone restaurants, but last weekend I stumbled upon two letters to investors from the Physical Culture Restaurant Company headed by fitness and health food advocate Bernarr Macfadden [shown above, age 42].

Macfadden was a body-builder, natural food proponent, and entrepreneur who decided to spread the gospel by opening inexpensive, largely plant-based restaurants at the turn of the last century. He attributed his strength and energy to this special diet.

The 1904 end-of-year letter reported that four new restaurants had been added to the ten already in business, and that they had done business totaling over $243,000, with a net gain of $2,637. Five restaurants had been judged failures and closed, four of them in NYC and one in Jersey City. He and his board of directors believed in rapidly shutting down locations that did not draw crowds. The letter blamed a “business depression” and the normally slow start of new locations for the smaller-than-hoped-for profits.

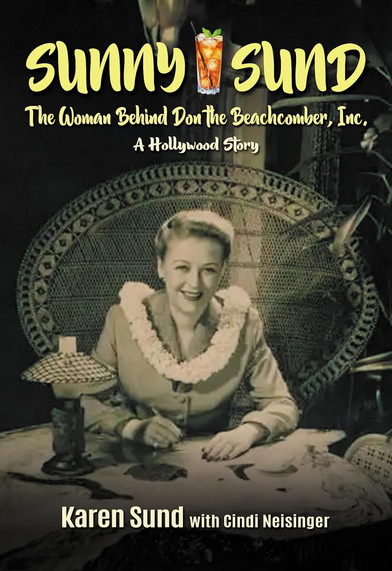

Although he wanted the restaurants to succeed, his personal income was not dependent upon them. Macfadden’s primary business was publishing periodicals, beginning in 1899 with Physical Culture, which discussed diet and health, followed by True Story, Liberty and then, increasingly, a large number of detective and romance magazines with titles such as Dream World, True Ghost Stories, and Photoplay. In addition he authored scores of books on fitness, sex, and health, and established a tabloid newspaper, The New York Evening Graphic. His publications earned him a fortune.

The total number of Macfadden restaurants open at the same time never seemed to exceed sixteen or so. The first ones were in New York City, of which there were nine at one point. Others were spread across the East and Midwest, including Boston, Newark, Jersey City, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis. There was also one in Toronto. [above: 1906 advertisement and 1906 restaurant at 106 E. 23rd, NYC]

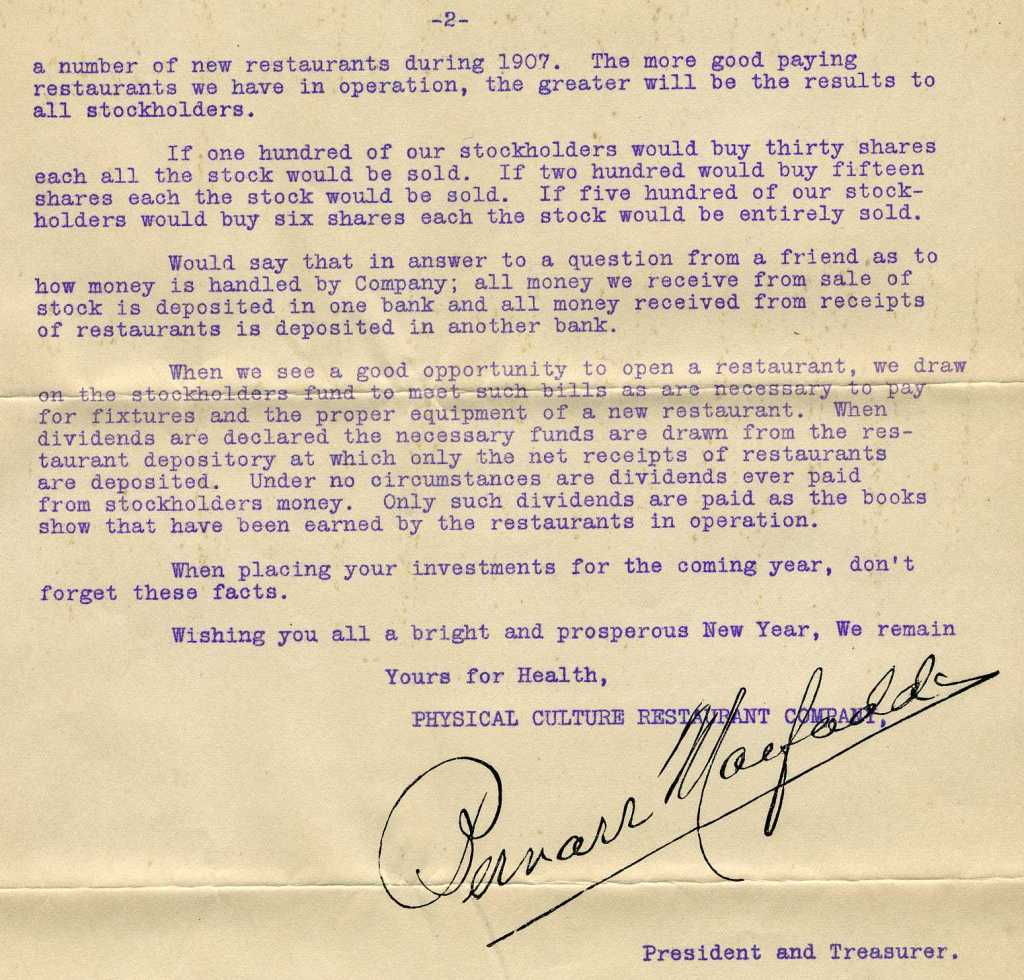

In the 1907 letter to stockholders shown above he floated the idea that the restaurant holdings might grow to 40 or 50 units if stockholders invested in more stock. This never happened.

Despite the growing popularity of the restaurants, it seems that for Macfadden they served primarily as a way to spread the gospel of a healthful diet. He could not be described as a restaurateur. No doubt he helped to conceptualize the restaurants and make up the early menus, but he did not manage them except in his role as corporate executive.

Prices were low in his early restaurants. A bowl of thick pea soup was 1c, as was a bowl of steamed hominy or oats or barley. Whole wheat bread and butter, however, cost 5c as did creamed beans or whole wheat date pudding. He sold loaves of whole wheat bread for 10c. [shown above]

A Macfadden menu shown in a 1919 British book reveals a wealth of choices then but also higher prices that reflect post WWI inflation. Five cents now bought less. Mushrooms on Toast cost 20c, as did meat substitutes Nuttose and Protose. A Macaroni Cutlet or Lentil Croquettes cost 25c, while omelets such as Mushroom, Walnut and Pecan, Orange, or Protose and Jelly were 30c.

In 1931, at which point only three Physical Culture restaurants remained, Macfadden gave up his fortune, said to be $5,000,000, and created the Bernarr Macfadden Foundation. In a radio broadcast he said: “It is a source of indescribable relief to feel like a free man again. Too much money unwisely used makes people greedy and ungrateful, destroys the home, steals your happiness, enslaves, enthralls you, lowers your vitality, and enfeebles your will.”

Yet his personal life continued to be full of numerous wives, affairs, and lawsuits. And, despite being “freed” of his fortune in 1931, he continued to spend money lavishly, taking it from the treasury of the Physical Culture Publishing Company after he turned that into a public corporation. Stockholders accused him of using nearly a million dollars for his own private interests, which included failed attempts to become a presidential candidate, governor of Florida, or mayor of New York.

In 1931 the Foundation opened the first of several Depression-era penny restaurants, no doubt modeled on Macfadden’s first restaurant at the beginning of the century where most dishes cost only one or a few cents. The initial Depression “pennyteria,” run by the Foundation, was located in midtown NYC. Drawing a crowd of about 6,000 a day, it quickly became self-supporting.

At a penny restaurant run by the Foundation, one cent would buy any of the following: coffee, split pea soup, navy bean soup, lentil soup, green pea soup, creamed cod fish on toast, raisin coffee, honey milk tea, cabbage and carrot salad, steamed cracked wheat, hominy grits, raisins and prunes, bread pudding, whole wheat doughnuts, whole wheat bread, or whole wheat raisin bread.

As the operator of the 1930s restaurants, the Foundation proved more flexible than Macfadden about dietary standards, but evidently he still had some say over what was served. According to one account he agreed to let meat appear on the menu as well as dairy products. Meat took the form of beef cakes, beef stew, and chicken fricassee. But he stood firm about bread, insisting only whole wheat be served.

I found no trace of the Macfadden restaurants nor the Foundation’s penny restaurants in the 1940s. Macfadden largely faded from the headlines, dying in 1955 and leaving an estate valued at only $5,000.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.