Lunch clubs for working women appeared in American cities in the 1890s and early 20th century. In a fairly short time they stimulated the development of commercial cafeterias, as well as employee cafeterias in large companies.

Chicago was regarded as a prime incubator of the lunch club idea. In 1891 a group of alumnae of the prestigious Ogontz finishing school near Philadelphia opened a space for women workers on an upper floor of Chicago’s Pontiac Building. At the start the club charged 10 cents a year for membership, and sold sandwiches for 4 cents and milk, tea, or coffee for 2 cents each.

By the end of the nineteenth century, women’s lunch clubs could be found in other major cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Cleveland, and San Francisco, but not in the South. Some, such as three in NYC, were affiliated with churches. In Indianapolis, temperance supporters – members of the W.C.T.U. — ran a lunch club.

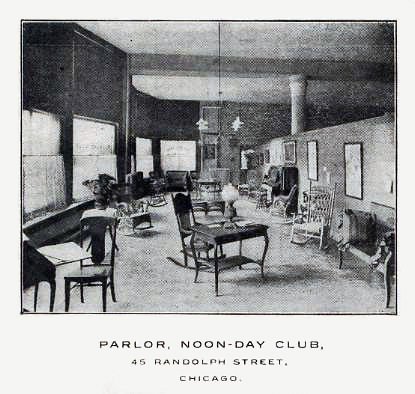

The lunch clubs were meant to provide not only inexpensive noontime meals for working women, but also to give them a place to enjoy a little leisure in “rest rooms” supplied with sofas, rocking chairs and desks, as well as libraries and other amenities. Some offered evening lecture series.

The clubs came at a time when the number of office workers in cities was on the increase. The clubs mainly catered to “business women,” which then meant young white-collar workers in offices and department stores. Although women factory workers had a greater need for restful and inexpensive lunches than did office workers, their shorter lunch breaks and lower pay made it difficult to accommodate them.

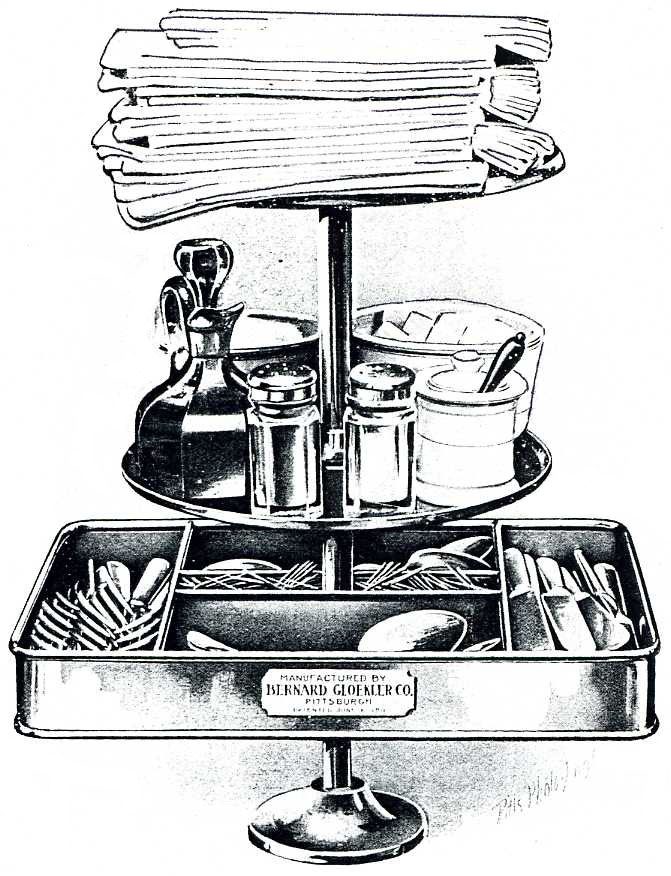

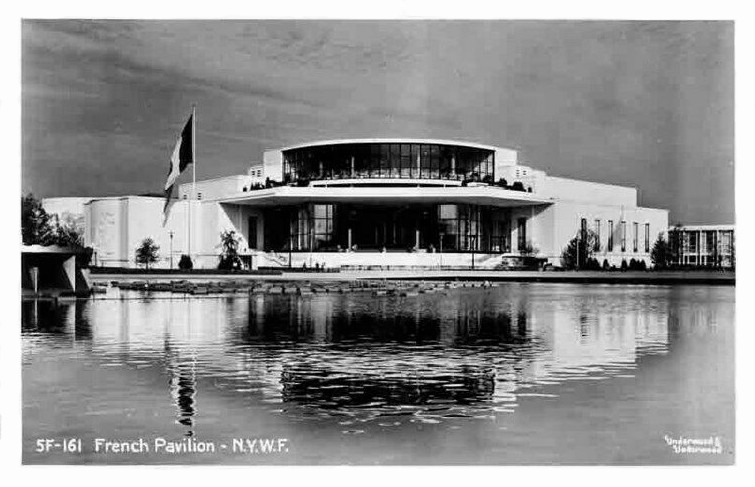

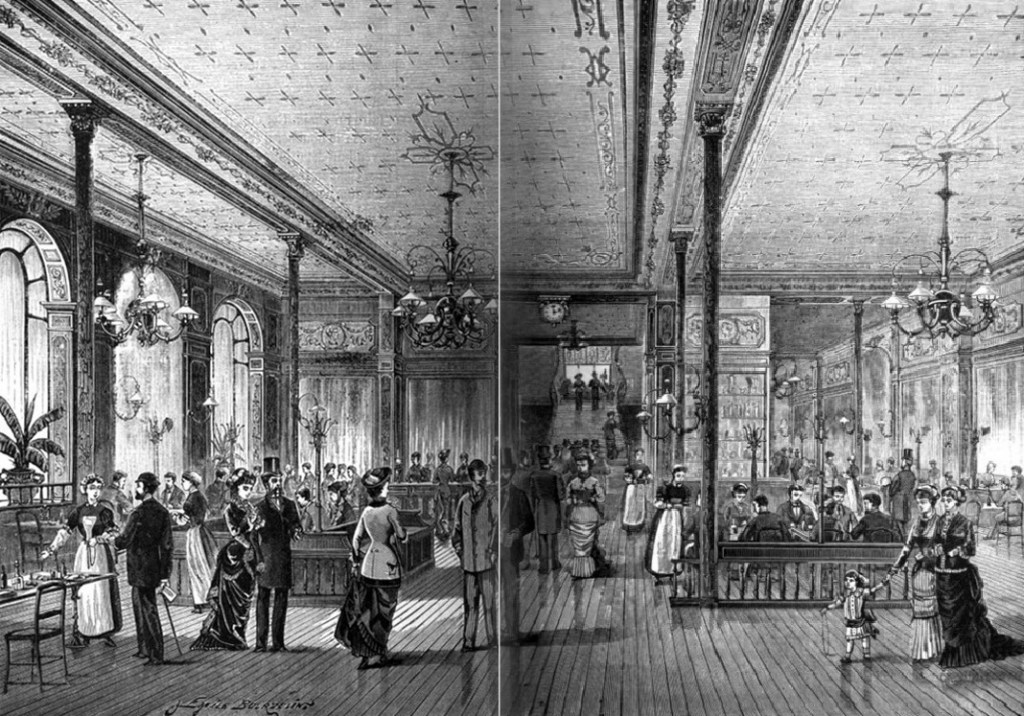

The earliest lunch clubs were launched by elite women as philanthropic projects to assist workers with affordable lunches, give them a place to hang out at noon, and to uplift them culturally. The food was not cooked on site, but supplied by other kitchens, such as that at Jane Addams’ Hull House in Chicago. To avoid the cost of hiring servers, food was set out on counters and diners selected what they wanted, a novel arrangement in the 1890s. [Above: Chicago’s Ursula lunch club, 1891] Prices were meant to cover costs but not to make a profit.

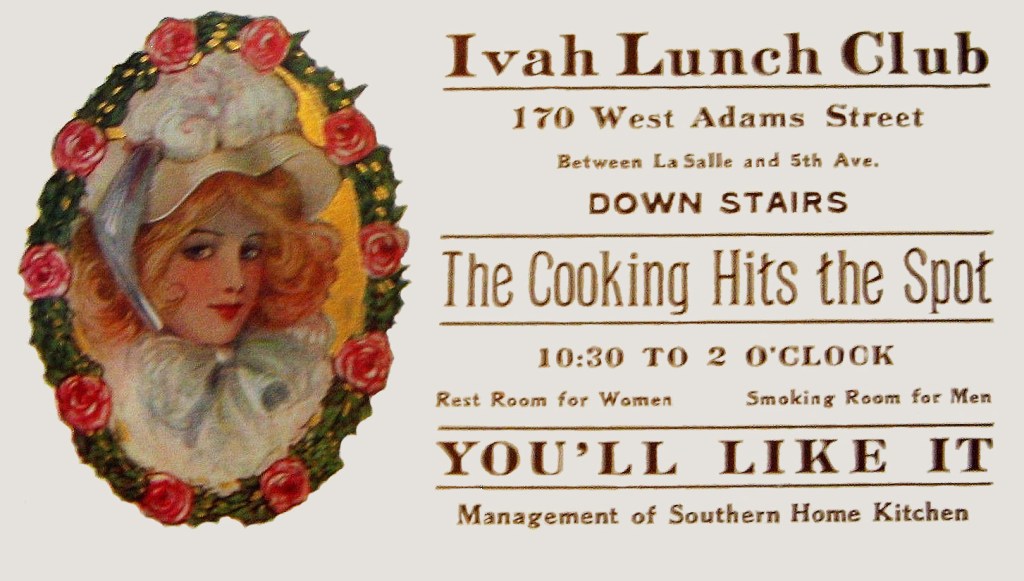

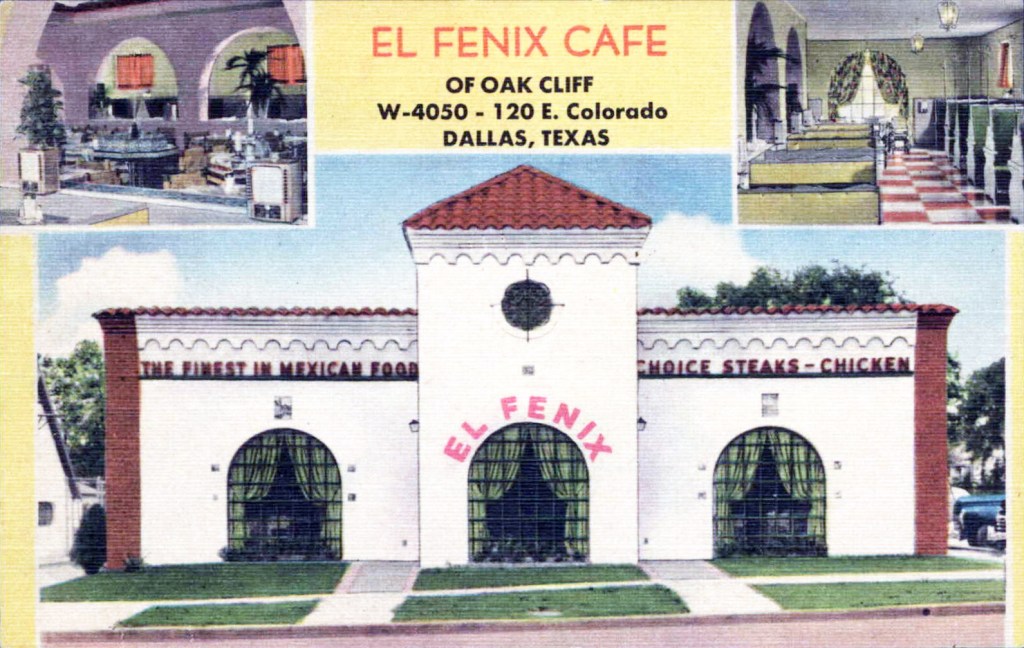

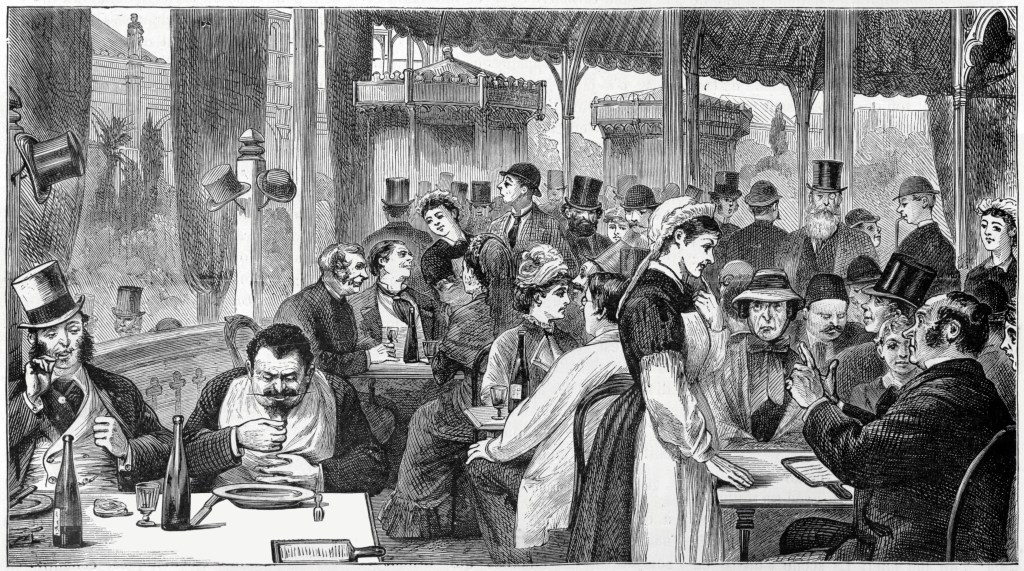

Lunch clubs had to tread a fine line in terms of how philanthropic backers related to the working women. At least one of the philanthropic lunch clubs made its lunchers feel pitied and failed to attract enough women. Those who had stuck with it then took it over as their own co-operative enterprise. Some other lunch clubs were begun as co-operatives. [Above: postcard of a commercial lunch club that admitted men]

A humorous turn-of-the-century story characterized the uneasy feeling of some working women toward philanthropy. In it, a wealthy man approaches a young sales clerk in a department store to say that he is thinking of starting a Noon-Day Rest Club, “where you and the others may come and drink Tea and listen to me read Advice to the Young.” She replies, “That would be lonely Billiards, wouldn’t it? We don’t want to be rounded up and sozzled over. Not on your Leaflards. The Poor Working Girl draws a line on having a kind-hearted Gentleman pull the Weeps on her. I think I can struggle along without having you come around to hold my Hand.”

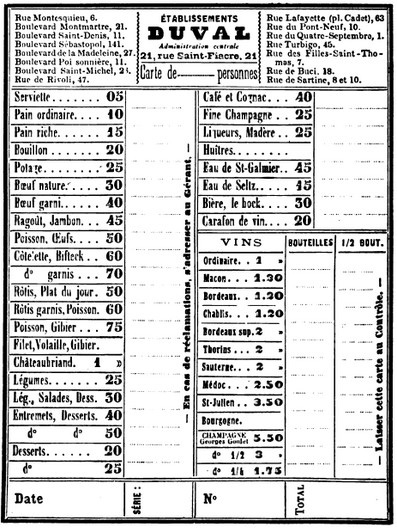

Despite this obstacle, lunch clubs proliferated. The Klio Club’s Noon-Day Rest expanded its menu, adding dishes such as soup, baked beans, and salmon salad. In 1899 a sample menu in one of Chicago’s six lunch clubs might have looked like this:

Two slices of bread or two rolls, with butter 5c

With jam or cold meat 6c

Extra butter 1c

Tomato soup, beef hash, Spanish stew 5c

Potato salad, sliced tomatoes, cucumbers, cottage cheese 5c

Tea or coffee, with cream 5c

With milk 3c

Iced tea, buttermilk 3c

Raspberry ice, lemon ice 5c

Vanilla ice cream, tutti-frutti ice cream 5c

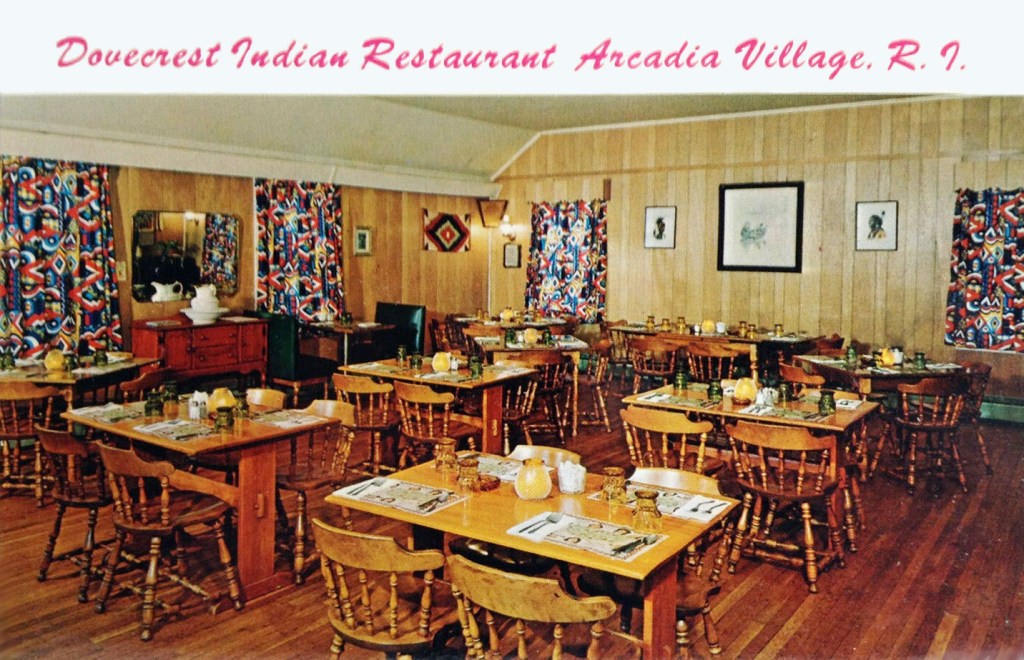

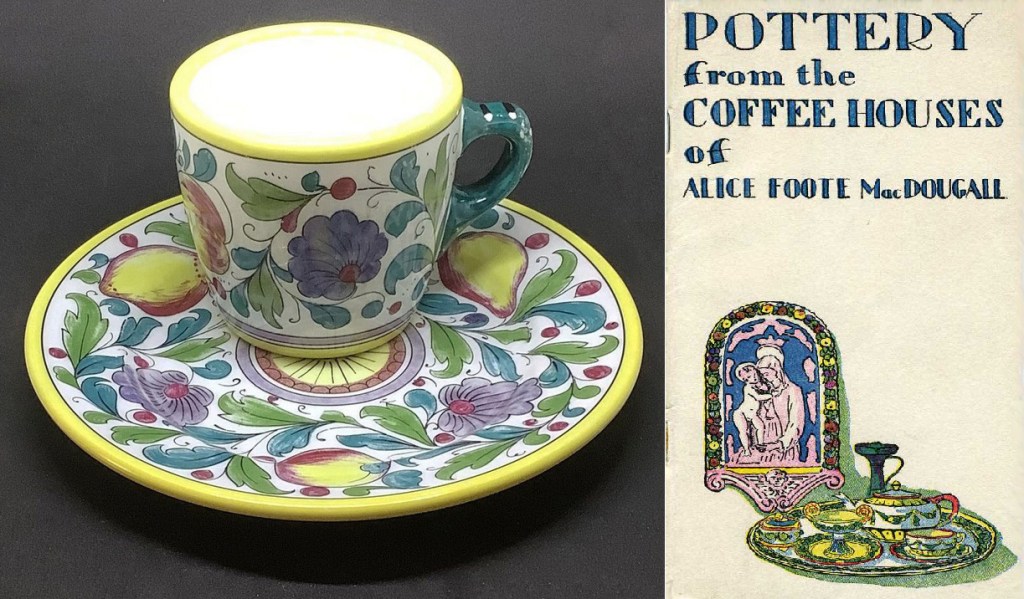

The success of serve-yourself lunch clubs spurred the development of commercial cafeterias. Over time it became harder for lunch clubs to attract large numbers of women patrons. Some began to accept men who, after all, tended to spend more for lunch. For-profit help-yourself businesses proliferated. In one case, a dispute at Klio’s Noon-Day Rest led its caterer, Kate Knox, to leave and start her own self-service lunch club business. [Mrs. Knox’s lunch club pictured above] Another enterprising woman, Mary Dutton, operated four cafeterias by 1915 after beginning with a single lunch club.

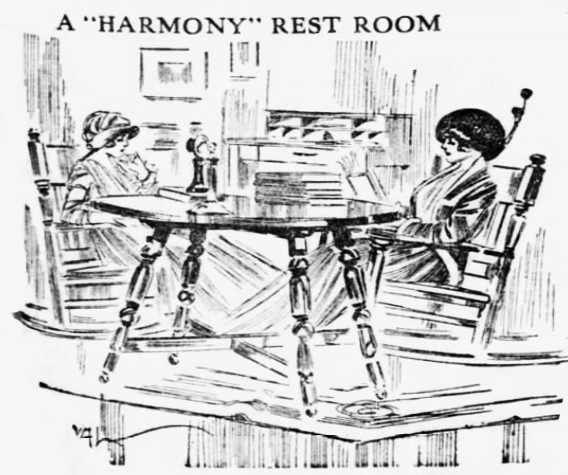

But the lunch clubs made an impact, for a time at least. Boston’s original noon-day lunch club closed because it felt it had elevated the standards of common restaurants. And businesses borrowed ideas from the lunch clubs. For example, The Harmony Cafeteria in Chicago, a commercial business, advertised in 1913 that it featured a basement rest area, with a drawing showing two women in rocking chairs reading books.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.