Taverns and inns of the Colonial and Early American eras were ancestors to hotels, providing the all-important trio of beds, food, and alcoholic drinks. But they also supplied inspiration to eating places in later centuries, particularly tea rooms and, to a lesser extent, steak houses.

Taverns and inns of the Colonial and Early American eras were ancestors to hotels, providing the all-important trio of beds, food, and alcoholic drinks. But they also supplied inspiration to eating places in later centuries, particularly tea rooms and, to a lesser extent, steak houses.

One of the most prominent features of taverns were their signboards. Borrowed from England and Europe, they depicted images of military heroes, courtly symbols, and local landmarks, with names to match. Animals of various colors were especially popular such as the White Swan, the Golden Horse, the Black Bear, or the Red Lion.

Taverns actually had dual names, the proprietor’s and that of the image on the sign. Signs were linked to a place. Proprietors might move from tavern to tavern but signs stayed where they were. For example, a Boston tavern keeper of the 1760s named Francis Warden advertised that he kept a “public house of entertainment” at the sign of the Green Dragon. Earlier he had been at the Blue Anchor.

Tavern signs have often been admired for their originality, but even in the 18th century they were stereotyped. Artists who painted them often advertised that they had a stock of signs on hand and ready to go except for the lettering. This undoubtedly accounts for the many taverns called The White Horse, The Beehive [illustrated above], The Three Crowns, or The Bunch of Grapes.

By the start of the 19th century the reign of taverns was slowly coming to an end and being replaced by larger hotels. The decline of the tavern was hastened by the temperance movement in the 1830s and 1840s which saw them as dens of iniquity. A temperance advocate suggested tavern signs should bear truthful names such as “The Widow and Orphans Manufactory” or “The New England Rum Pit.” As towns outlawed the sale of liquor, many old tavern signs were pulled down and replaced with signs saying Temperance Hotel.

By the start of the 19th century the reign of taverns was slowly coming to an end and being replaced by larger hotels. The decline of the tavern was hastened by the temperance movement in the 1830s and 1840s which saw them as dens of iniquity. A temperance advocate suggested tavern signs should bear truthful names such as “The Widow and Orphans Manufactory” or “The New England Rum Pit.” As towns outlawed the sale of liquor, many old tavern signs were pulled down and replaced with signs saying Temperance Hotel.

As taverns declined, nostalgia began to develop for their Days of Olde when jolly hosts greeted guests and ushered them inside to sip hot toddies at the fireplace. Books and newspaper stories appeared describing quaint tavern signs and names of yesteryear. Historical societies became interested in preserving the increasingly scarce old signs. A Boston lodge of the Masons fraternal organization which had been founded in The Bunch of Grapes acquired two of the four carved wooden bunches in 1883 and locked them away in a steel vault. A collector in Pennsylvania treasured a sign he discovered in the 1890s that had been painted in 1771 by famous English artist Benjamin West.

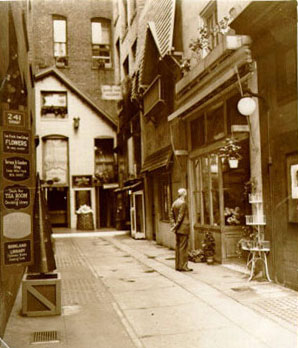

Women, particularly those New Englanders who could trace their ancestry to Colonial times, became supporters of the preservation of American antiquities. Newly possible car travel encouraged them to explore former taverns in the countryside. Next they began to open tea rooms that celebrated Early America, many with names and signs from tavern days. It was as though taverns had returned, clean, ultra-respectable and without liquor and drunkenness. Tea, after all, was known as “the cup that cheers but does not inebriate.”

Women, particularly those New Englanders who could trace their ancestry to Colonial times, became supporters of the preservation of American antiquities. Newly possible car travel encouraged them to explore former taverns in the countryside. Next they began to open tea rooms that celebrated Early America, many with names and signs from tavern days. It was as though taverns had returned, clean, ultra-respectable and without liquor and drunkenness. Tea, after all, was known as “the cup that cheers but does not inebriate.”

One feature that did not survive was the political statement tavern signs had made back in the days when their keepers sided either with the British crown or the rebellious patriots. Another oddity was how many tea rooms adopted names that incorporated the words “At the Sign of” – preceding “the Green Kettle,” “the Golden Robin,” etc. Where a tavern of 1800 advertised it could be found “At the Sign of the Seven Stars,” a 20th-century tea room, had it used the same style of advertising, would have had to say it was “At the Sign of At the Sign of the Seven Stars.” The sign of At the sign of The Tea-Kettle and Tabby Cat adorned a tea room in Wenham MA.

One feature that did not survive was the political statement tavern signs had made back in the days when their keepers sided either with the British crown or the rebellious patriots. Another oddity was how many tea rooms adopted names that incorporated the words “At the Sign of” – preceding “the Green Kettle,” “the Golden Robin,” etc. Where a tavern of 1800 advertised it could be found “At the Sign of the Seven Stars,” a 20th-century tea room, had it used the same style of advertising, would have had to say it was “At the Sign of At the Sign of the Seven Stars.” The sign of At the sign of The Tea-Kettle and Tabby Cat adorned a tea room in Wenham MA.

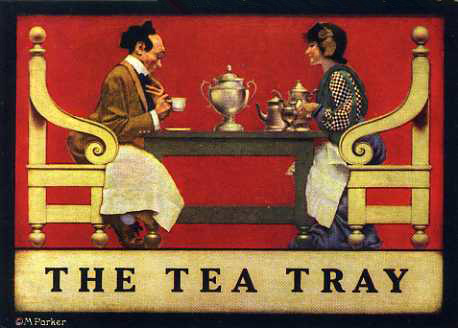

The sign for the Tea Tray, a tea room in Cornish NH, was painted by Maxfield Parrish and shows much more detail than old tavern signs would have included.

In the 1960s and 1970s some steak houses also adopted a tavern theme, with names such as Steak & Ale, Bird & Bottle, or Cork & Cleaver, but only as a superficial concept that did not include revival of old-fashioned signboards.

© Jan Whitaker, 2015

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.