As alcoholic beverages made their return in the early 1930s, supper clubs and roadhouses offering meals, entertainment, and good cheer sprang up on highways and byways across the nation. Eager to attract customers, some adopted unusual designs that, on the surface at least, promised something out of the ordinary.

As alcoholic beverages made their return in the early 1930s, supper clubs and roadhouses offering meals, entertainment, and good cheer sprang up on highways and byways across the nation. Eager to attract customers, some adopted unusual designs that, on the surface at least, promised something out of the ordinary.

One of them was Salvatore “Toto” Lobello’s place on the main road leading from Holyoke to Northampton MA. It looked like the German Graf Zeppelin that was always in the news with tales of travelers gliding through the sky while enjoying its deluxe dining and sleeping accommodations.

One of them was Salvatore “Toto” Lobello’s place on the main road leading from Holyoke to Northampton MA. It looked like the German Graf Zeppelin that was always in the news with tales of travelers gliding through the sky while enjoying its deluxe dining and sleeping accommodations.

The fantastic building was a type of roadside architecture of the late 1920s and 1930s commonly associated with California where sandwich shops and refreshment stands resembled oversized animals and objects ranging from toads to beer kegs. The zeppelin-shaped building was constructed in 1933 by Martin Bros., a well-known Holyoke contractor experiencing serious financial distress at that time. The nightclub apparently failed to open and, in 1934, suffered fire damage (for the first, but not the last, time).

In December of 1935, after months of trying to obtain a liquor license, Toto Lobello announced the grand opening of the Zeppelin. He solved the licensing problem by teaming up with Lillian and Adelmar Grandchamp who were able to transfer the license from their recently closed downtown Holyoke restaurant, the Peacock Club.

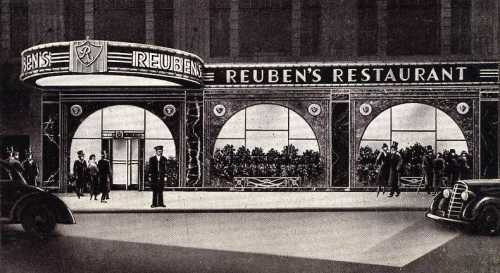

The advertisement for the opening of “New England’s Smartest Supper Club” announced that drinks would be available in the Modernistic Cocktail Lounge, which was on the ground floor below the dirigible-shaped dance hall. With Web Maxon and his orchestra providing dance music, and a promise of “Never a Cover Charge, Always a Good Time,” the Zeppelin soon became a popular place for nightlife generally and for dinner parties of organizations such as the Elks and the Knights of Columbus.

The advertisement for the opening of “New England’s Smartest Supper Club” announced that drinks would be available in the Modernistic Cocktail Lounge, which was on the ground floor below the dirigible-shaped dance hall. With Web Maxon and his orchestra providing dance music, and a promise of “Never a Cover Charge, Always a Good Time,” the Zeppelin soon became a popular place for nightlife generally and for dinner parties of organizations such as the Elks and the Knights of Columbus.

Toto Lobello also had a confectionery business in Northampton located on Green Street across from the campus of the all-women Smith College. Like the confectionery, the Zeppelin became one of the students’ favorite haunts for the 3-Ds (dining, dancing, and drinking). According to an informal survey in 1937 the majority of Smith students liked to drink, preferring Scotch and soda, champagne, and beer. Toto’s ranked as a top date destination.

Toto Lobello also had a confectionery business in Northampton located on Green Street across from the campus of the all-women Smith College. Like the confectionery, the Zeppelin became one of the students’ favorite haunts for the 3-Ds (dining, dancing, and drinking). According to an informal survey in 1937 the majority of Smith students liked to drink, preferring Scotch and soda, champagne, and beer. Toto’s ranked as a top date destination.

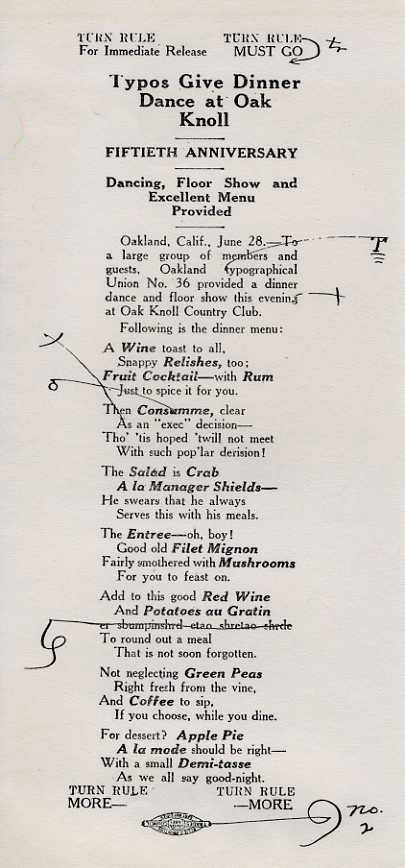

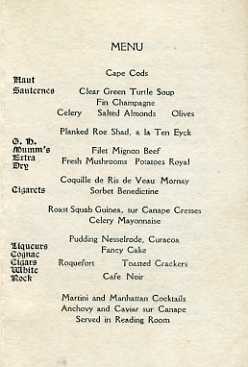

Toto’s Zeppelin served lunch and dinner and a special Sunday dinner for $1.00. On Saturday nights Charcoal Broiled Steak was featured.

One year after Toto’s grand opening the restaurant/nightclub faced a licensing renewal challenge requiring it to withdraw its application until unspecified “improvements” were made to the facility. But a more serious problem was about to emerge when dirigibles suddenly lost their appeal following the May 1937 Hindenburg disaster in which 36 people perished. Not too much later, in November of 1938, fire would also completely destroy Holyoke’s Zeppelin. In rebuilding, Toto chose a moderne style with a pylon over the entrance.

In the mid-1950s Salvatore Lobello, owing the state a considerable sum for unpaid unemployment taxes, filed for bankruptcy. He closed his Northampton restaurant, auctioning off all the fixtures in 1957. The building, at the address now belonging to a pizza shop, was razed. The Holyoke restaurant continued in business until 1960 when it was seized by the federal government for nonpayment of taxes. It briefly did business as the Oaks Steak & Rib House, a branch of the Oaks Inn of Springfield, before its destruction by fire in 1961. [above, facing pages from the drinks menu, ca. 1950s, courtesy of “a lover of the 1930s, cocktails, and zeppelins.”]

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.