In the modern world nothing is more expensive than quiet. This certainly holds true for restaurants. The difference between a quiet and a noisy restaurant rests mainly on good padding, both of the room and the patron’s wallet.

In the modern world nothing is more expensive than quiet. This certainly holds true for restaurants. The difference between a quiet and a noisy restaurant rests mainly on good padding, both of the room and the patron’s wallet.

But there is also such a thing as too much quiet, such as in a failing restaurant with few patrons. Nobody wants that kind of quiet. Which brings up the point that since the proliferation of theme restaurants in the 1970s, fun has become one of the biggest attractions for restaurant goers. And in most people’s minds fun = noise and crowds.

It seems as though since the 1970s noise has crept up the restaurant ladder, beyond the raucousness of TGI Friday and its kin, so that today even many fairly expensive, white-tablecloth restaurants are so noisy that conversation is difficult. This issue was called to my attention by a friend who asked where she could find a list of restaurants that are free of din. If anyone knows of such a thing, please let me know. With an aging population – older diners, particularly in the 55 to 65 year-old range, make up a sizable market – the noise problem becomes more pressing.

It seems as though since the 1970s noise has crept up the restaurant ladder, beyond the raucousness of TGI Friday and its kin, so that today even many fairly expensive, white-tablecloth restaurants are so noisy that conversation is difficult. This issue was called to my attention by a friend who asked where she could find a list of restaurants that are free of din. If anyone knows of such a thing, please let me know. With an aging population – older diners, particularly in the 55 to 65 year-old range, make up a sizable market – the noise problem becomes more pressing.

Although the popularity of restaurant-going is comparatively new, complaints about restaurant din are not. In 1848 a satirical essay in that fascinating periodical The Spirit of the Times (“A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature” – and almost everything else) said:

It has been ascertained that a gentleman never enjoys his dinner more than when it is served up in the midst of confusion, excitement, and noise. For this reason, the denizens of New York, observing and sagacious, delight to dine in cellars, and wisely select those which the most boisterous people frequent.

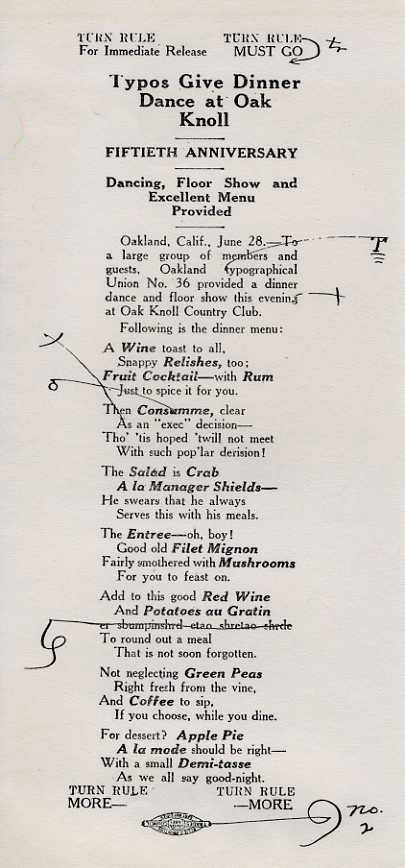

In 1869 another writer observed that at noon in downtown NYC “eating houses are in one continuous roar. The clatter of plates, the slamming of doors, the talking and giving of orders by the customers, the bellowing of waiters, are mingled in a wild chaos.” It would get worse. Restaurants became even noisier when music made its dining room debut, and again during World War II when they were packed to bursting capacity (see image). Cafeterias could be especially deafening.

In 1869 another writer observed that at noon in downtown NYC “eating houses are in one continuous roar. The clatter of plates, the slamming of doors, the talking and giving of orders by the customers, the bellowing of waiters, are mingled in a wild chaos.” It would get worse. Restaurants became even noisier when music made its dining room debut, and again during World War II when they were packed to bursting capacity (see image). Cafeterias could be especially deafening.

However, there were some exceptions along the way. The upstanding Craftsman Restaurant in NYC eschewed artificial gaiety. A diner in 1914 wrote (revealing the genteel racism of the period): “About me people were lunching quietly, without haste and without boisterousness. Soft-treading little men of Nippon brought delectable viands on dainty dishes. A stringed orchestra was playing softly . . .”

Tea rooms were also singled out in the teens and 1920s for their peacefulness. Very likely the absence of alcoholic beverages in them played a big role. NYC’s Colonia had “a quiet atmosphere that appeals to the woman of culture,” while in Greenwich Village the women proprietors of The Candlestick provided a luncheon setting “without the annoyance of shrieks, laughter, loud talking and noises that seem to be the necessary accessories of every other similar place in our Village, perhaps in order to create ‘bohemian atmosphere.’” Yet drinking did not inevitably lead to din. Rather surprisingly, the speakeasy restaurant was seen by some as a quiet, relaxing haven where attentive waiters served well-behaved patrons united in a “civilized conspiracy.”

Tea rooms were also singled out in the teens and 1920s for their peacefulness. Very likely the absence of alcoholic beverages in them played a big role. NYC’s Colonia had “a quiet atmosphere that appeals to the woman of culture,” while in Greenwich Village the women proprietors of The Candlestick provided a luncheon setting “without the annoyance of shrieks, laughter, loud talking and noises that seem to be the necessary accessories of every other similar place in our Village, perhaps in order to create ‘bohemian atmosphere.’” Yet drinking did not inevitably lead to din. Rather surprisingly, the speakeasy restaurant was seen by some as a quiet, relaxing haven where attentive waiters served well-behaved patrons united in a “civilized conspiracy.”

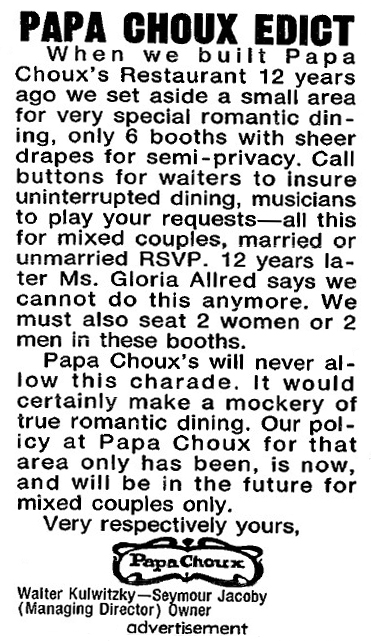

Quiet has also been seen as a necessary condition for a romantic dinner. But let’s note that on such an occasion diners are usually willing to fork out a bit more cash than usual for privacy and a chance to hear the cork pop and the harp being plucked. The question remains: can a restaurant that is thriving be quiet without being expensive?

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.