Compared to cities of comparable size in 1910 — such as Los Angeles, Minneapolis, or New Orleans — Milwaukee at first appears to be a town where people rarely ate outside the home. But statistics can be deceiving. In the city made famous by its breweries, most eating places were primarily saloons before Prohibition, usually set up in business by one or another brewery.

Compared to cities of comparable size in 1910 — such as Los Angeles, Minneapolis, or New Orleans — Milwaukee at first appears to be a town where people rarely ate outside the home. But statistics can be deceiving. In the city made famous by its breweries, most eating places were primarily saloons before Prohibition, usually set up in business by one or another brewery.

This is how Charles Mader got his start, as a saloonkeeper who also served meals of the homely sort. Although 1902 is commonly given as the year in which he began, I suspect it was a few years later that he opened his own place. Throughout most of his early career he worked with a partner. He and Gustav Trimmel joined up in 1915, the year the saloon moved to the present-day restaurant’s address. In 1921 Mader had a new partner, Charles Ruge, with whom he remained in business until 1928. Thereafter his partners were his sons George and Gus who assumed ownership when Charles died in 1937. [pictured above, 1950s]

Although many restaurants get a good share of patronage from out-of-towners, relatively few located in America’s midsection make a determined bid for nation-wide recognition. Mader’s was one of those that did so successfully. A late 1920s photograph in the historic photo collection of the Milwaukee Public Library shows the restaurant with a prominent “Tourists’ Headquarters” sign in its front window. In 1929, a newspaper item suspiciously resembling an advertorial (publications didn’t identify them as such then) claimed that Mader’s had won a reputation for hospitality extending “the length and breadth of this land and to distant lands as well.”

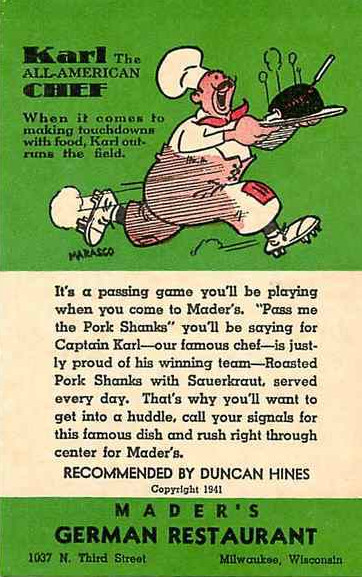

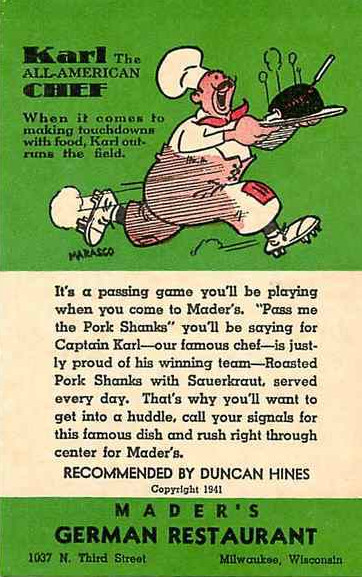

Charles Mader was known for his belief in advertising, often remarking, “If your business is not worth advertising, advertise it for sale.” Beginning afer Prohibition, Mader’s would intensify its advertising program and accentuate its Germanness, following a kind of reverse assimilation common to other German-themed restaurants in the US. Very likely this reflected a proportionate shift in patronage from German-American Milwaukeans to a wider clientele of conventioneers, traveling businessmen, and tourists of all stripes looking for an identifiably ethnic experience. The trend would continue: a 1968 newspaper story reported that at Mader’s and Karl Ratzsch’s, mostly patronized by tourists, German dishes were popular, while at restaurants patronized exclusively by Milwaukeans such as the Fox and Hounds, filet mignon and lobster tail were favorites.

Charles Mader was known for his belief in advertising, often remarking, “If your business is not worth advertising, advertise it for sale.” Beginning afer Prohibition, Mader’s would intensify its advertising program and accentuate its Germanness, following a kind of reverse assimilation common to other German-themed restaurants in the US. Very likely this reflected a proportionate shift in patronage from German-American Milwaukeans to a wider clientele of conventioneers, traveling businessmen, and tourists of all stripes looking for an identifiably ethnic experience. The trend would continue: a 1968 newspaper story reported that at Mader’s and Karl Ratzsch’s, mostly patronized by tourists, German dishes were popular, while at restaurants patronized exclusively by Milwaukeans such as the Fox and Hounds, filet mignon and lobster tail were favorites.

In 1935 the Maders remodeled the 3rd Street building to look more typically German in a style suggestive of medieval architecture with a high stepped gable and two bas relief panels depicting quaintly costumed servers. By contrast, only a couple years earlier Mader’s had a typical plate glass storefront with a centered, recessed entryway and a moderne sign with its name spelled out in bold aluminum lettering. In subsequent decades, the Mader’s compound has been further extended and embellished, given a vaulted ceiling and decorated with heraldic swords and shields. It has taken on a castle-like appearance.

In 1935 the Maders remodeled the 3rd Street building to look more typically German in a style suggestive of medieval architecture with a high stepped gable and two bas relief panels depicting quaintly costumed servers. By contrast, only a couple years earlier Mader’s had a typical plate glass storefront with a centered, recessed entryway and a moderne sign with its name spelled out in bold aluminum lettering. In subsequent decades, the Mader’s compound has been further extended and embellished, given a vaulted ceiling and decorated with heraldic swords and shields. It has taken on a castle-like appearance.

Along with arch competitor Karl Ratzsch’s, a Viennese-inflected restaurant pursuing much the same strategy, Mader’s began to win awards and listings in national magazines and restaurant guides, such as Duncan Hine’s Adventures in Good Eating and those of the Automobile Club of America and Ford Motor Company. It began attracting visiting Hollywood stars in the 1930s, hanging their autographed photos on its walls. In 1937 and again in 1949 and 1952 a poll of traveling business men voted it America’s favorite German restaurant and one of their ten favorite restaurants overall. Accolades continued coming in up to the present day.

Along with arch competitor Karl Ratzsch’s, a Viennese-inflected restaurant pursuing much the same strategy, Mader’s began to win awards and listings in national magazines and restaurant guides, such as Duncan Hine’s Adventures in Good Eating and those of the Automobile Club of America and Ford Motor Company. It began attracting visiting Hollywood stars in the 1930s, hanging their autographed photos on its walls. In 1937 and again in 1949 and 1952 a poll of traveling business men voted it America’s favorite German restaurant and one of their ten favorite restaurants overall. Accolades continued coming in up to the present day.

Mader’s is a survivor, having outlasted most of Milwaukee’s venerable German restaurants, some of which, Forst-Keller and the Old Heidelberg for example, were associated with the city’s breweries. Cafes originating with Fritz Gust, Joe Deutsch, and John Ernst have all passed from the scene, the last as recently as 2001.

Long considered “heavy” eating, German cuisine has perhaps sunk in popularity somewhat from the middle of the 20th century, although Pork Shanks – ever popular at Mader’s – remain on the restaurant’s menu to this day. Notably, though, this once-humble dish has become an expensive entree.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

Iffland’s was established on Market street in Newark in 1867, just one year after John Iffland immigrated from Germany at the age of 25. [He is pictured here at about 51.] A few years later he moved to 187 Market, the location shown on the postcard.

Iffland’s was established on Market street in Newark in 1867, just one year after John Iffland immigrated from Germany at the age of 25. [He is pictured here at about 51.] A few years later he moved to 187 Market, the location shown on the postcard.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.