Although toothpicks have many uses in the home, their career as a tool for picking teeth is mostly associated with restaurants. And, like so many aspects of restaurant history, their story says a lot about social class. The short version is that when using toothpicks was viewed as a custom of European elites it was approved in the U.S., but when American working class men adopted it, it became taboo. Today the use of toothpicks after a meal is infrequent compared to what it was roughly 100 years ago when it was at its peak.

In the Quick Lunch era of the early 20th century, toothpicks became more than a means to loosen bits of food stuck in tooth crevices. They were assertions of masculinity, essential accessories for the male lunchroom crowd. A dangling toothpick sent a macho signal as speedily as a cigarette between the lips of 1960s filmstar Jean Paul Belmondo.

In the 1890s lunchroom patrons felt entitled to toothpicks just as much as to a paper napkin and a glass of water. When a distinguished Afro-American man was told by a Kansas City restaurateur in 1890 that he would be charged an exorbitant $1 for pie and coffee, he seemed to consent but later walked out saying “Sue me for the rest” as he tossed a dime on the counter. And he grabbed a handful of toothpicks on the way, staking a claim to equality in an unmistakable fashion.

In the 1890s lunchroom patrons felt entitled to toothpicks just as much as to a paper napkin and a glass of water. When a distinguished Afro-American man was told by a Kansas City restaurateur in 1890 that he would be charged an exorbitant $1 for pie and coffee, he seemed to consent but later walked out saying “Sue me for the rest” as he tossed a dime on the counter. And he grabbed a handful of toothpicks on the way, staking a claim to equality in an unmistakable fashion.

Arbiters of etiquette deplored toothpicks. Starting in the late 19th century when the picks came into fairly common use in the United States, and for the next 100 years at least, a string of advice columnists from Mrs. John Sherwood to Ann Landers railed against them. All declared using toothpicks in public vulgar and disgusting. “Dear Abby” echoed her forebears when she roundly condemned public toothpick use in 1986, calling it “crude, inconsiderate, and a show of bad manners.”

Goose quill toothpicks had been acceptable in the early republic, furnished even at such elite places as Delmonico’s. But as mass-produced wooden picks made of birch and poplar became available in the 1870s, prices fell drastically until even the cheapest eatery could afford to dispense them. Their social status plummeted.

Goose quill toothpicks had been acceptable in the early republic, furnished even at such elite places as Delmonico’s. But as mass-produced wooden picks made of birch and poplar became available in the 1870s, prices fell drastically until even the cheapest eatery could afford to dispense them. Their social status plummeted.

Toothpick haters frequently pointed out that providing toothpicks in restaurants was as ridiculous as handing out toothbrushes. It’s interesting that in the early 20th century another form of tabletop hygiene, the finger bowl, was also about to go under attack. Strangely, since toothpicks and finger bowls were intended for cleanups, they were criticized as germ spreaders. Because toothpicks were provided loose in a bowl or cup, restaurant patrons often grabbed them helter skelter, fingering many they left behind. Trains eliminated them in their dining cars and Minneapolis health authorities banned open containers of toothpicks in 1917.

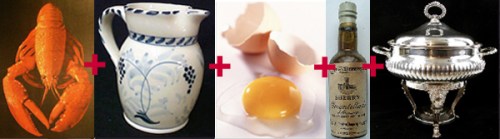

Another solution to the germy toothpick bowl and the habit of grabbing handfuls was bound to occur to America’s legion of gadget inventors. Presto! One-at-a-time toothpick dispensers. [shown here and in restaurant above, the Dial-A-Pic]

Another solution to the germy toothpick bowl and the habit of grabbing handfuls was bound to occur to America’s legion of gadget inventors. Presto! One-at-a-time toothpick dispensers. [shown here and in restaurant above, the Dial-A-Pic]

Restaurant owners would have been just as happy to see toothpicks disappear altogether. A NYC restaurant owner confessed in 1904 that he disliked the sight of men picking their teeth at his tables as much as that of others sticking knives in their mouths. But he took a pragmatic stance, admitting that “we cannot conduct examinations in table manners before we admit persons to our dining-rooms.”

Today toothpick usage is reportedly unpopular with younger diners and has been dropping off since World War II. So I was surprised to see a little cup of wrapped toothpicks in an upscale restaurant in Kansas City this weekend. Now I’ll be on the lookout everywhere I go.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.