Café Society was the satirical name of a New York jazz club in the late 1930s and 1940s. The name was meant to make fun of people who wanted to be seen as sophisticated rather than merely rich. However, it’s likely that Café Society nevertheless proved to be an attraction to many of those same people.

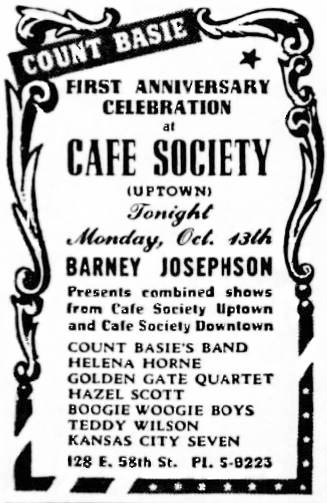

By the second year there were two locations of Café Society, Downtown and Uptown. The clubs and their owner Barney Josephson have become well known for the number of jazz greats they introduced and nurtured, among them Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, and Teddy Wilson. And also for their full acceptance of Black customers.

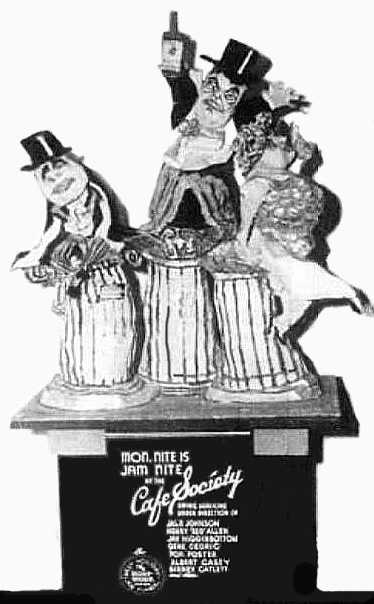

Unlike other “café society” club owners such as the Stork Club’s, Josephson refused to accept the racial codes of that time. He was determined not to follow policies that featured Black performers but would not allow them to mingle with the patrons, and excluded Black guests. Even when these policies began to soften, it was common for Black patrons to be seated inconspicuously in the least desirable spots. [Above: 1939 sign at the Downtown club ridiculing prominent society figures]

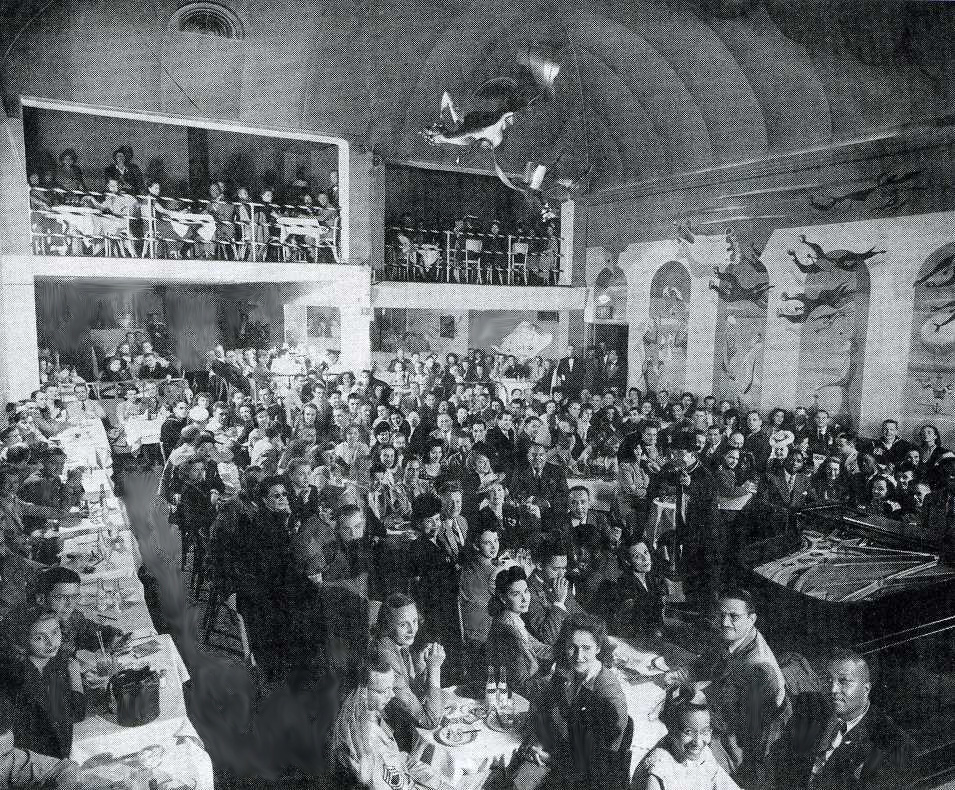

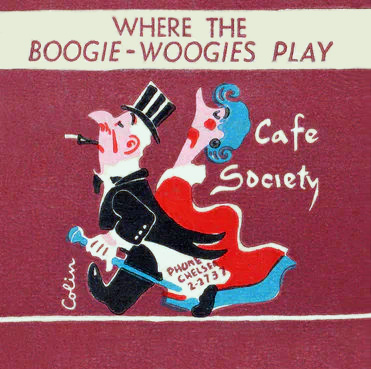

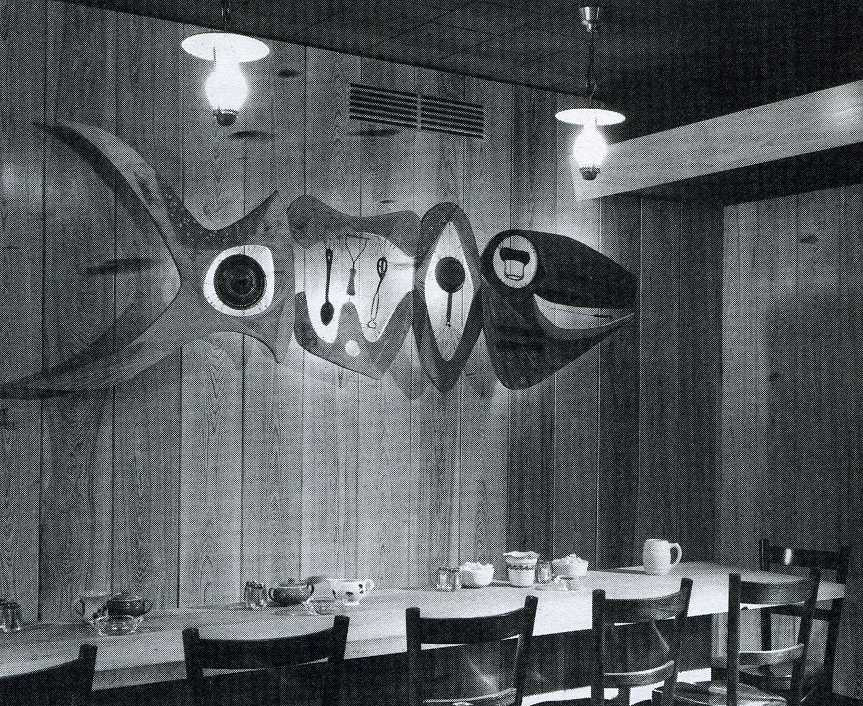

When he opened the Downtown Greenwich Village club in late December 1938, Barney recruited three musicians who had been part of a Carnegie Hall Christmas Eve program called From Spirituals to Swing. Albert Ammons, Meade Lux Lewis, and Pete Johnson performed at the club a few days later. The club advertised that it featured “boogie-woogie,” which was largely unknown in New York City at the time. [Above: Downtown in 1939; William Gropper mural]

But what about the food? In general, jazz clubs’ culinary output has not been regarded as the finest. Barney claimed that when he started out, most jazz clubs were run by mobsters who didn’t even try to prepare good meals. He tried to do better, but it’s hard to judge how well he succeeded since I’ve found little commentary. Club cuisine wasn’t usually written about.

In a book based on recordings of his memories, published by his fourth wife after his death, Barney commented that in most nightclubs waiters were urged to push drinks not food. For the Uptown Café Society (on East 58th), opened about a year later than Downtown, he made an effort to provide good food by hiring a chef who had managed the Claremont Inn and had been head waiter at Sherry’s. Robert Dana, nightclub editor of the Herald Tribune, was of the opinion that “On its food alone, Café Society ranked with many fine restaurants,” singling out squab chicken casserole and cream of mushroom soup. [Above: Uptown, 1943; Below: Advertisement with the musical lineup on Uptown’s first anniversary, 1940]

By the end of 1947 Uptown was out of business, and Downtown closed in early March of 1949. The problem was that Barney’s brother Leon, an admitted Communist Party member, was part owner of the clubs, having advanced start-up money. In 1947 Leon was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, refused to testify, and spent a year in prison. Barney was seen as guilty by association, attendance at his clubs plummeted, and he lost all his money. It seemed his career as a jazz club owner was over.

After that he concentrated on the restaurant business. He opened three restaurants, all called The Cookery, with one on Lexington across from Bloomingdale’s, one on 52nd Street in the CBS building, and then in 1955 a third one in Greenwich Village on University Place and 8th Street. The first two did not stay open long, but the Greenwich Village site was successful. [Above: The Cookery on Lexington; wall art by Anton Refregier]

While the two Café Societies had featured jazz with food, his third Cookery was to become a purveyor of food with jazz.

The Village’s Cookery was far from glamorous, generally described as “a hamburger, ham-and-egg type restaurant.” For the first 15 years there was no music. And then one day Barney had a visit from pianist Mary Lou Williams — who had played at Café Society Downtown – looking for work. As he described it:

“. . . this lady, one of the greatest musicians of all times, composer, arranger, not working? It was all this wild, crazy rock. . . . I investigated and found out I didn’t need a cabaret license in my place if I only had three string instruments.” [Above: Mary Lou Williams, at the Cookery in the Village, 1970]

So he told her to go rent a piano and, presto!, he was back in the jazz club business as of 1970. She was a draw. As he put it, “Mary returned to The Cookery each year through 1976 for three-month gigs, always to critical acclaim and crowds.” Other musicians who played there included Teddy Wilson, Marian McPartland, and the elderly singer Alberta Hunter, who had been working as a nurse.

The Cookery stayed in business until 1984.

For those interested in reading more about Barney’s clubs, see the book based on his recorded memoir published by Terry Trilling-Josephson in 2009 (Café Society: The wrong place for the Right people).

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

What could be more starkly different from the somber coffee shops of today with their earnest and wired denizens than the beatnik coffeehouses of the 1950s? Could Starbucks be anything but square to the beat generation?

What could be more starkly different from the somber coffee shops of today with their earnest and wired denizens than the beatnik coffeehouses of the 1950s? Could Starbucks be anything but square to the beat generation? Although the word beatnik came into usage around 1958 (inspired partly by Sputnik), the phenomenon of dropping out of the “rat race” to lead an existentialist, non-consumerist life was part of the aftermath of World War II akin to the “Lost Generation” after World War I. The first coffeehouses sprang up in Greenwich Village in the late 1940s, but the beats weren’t averse to hanging out in cafeterias either — their “Paris sidewalk restaurant thing of the time.” When coffeehouses began levying cover charges for performances, beatniks tended to drop out of them too.

Although the word beatnik came into usage around 1958 (inspired partly by Sputnik), the phenomenon of dropping out of the “rat race” to lead an existentialist, non-consumerist life was part of the aftermath of World War II akin to the “Lost Generation” after World War I. The first coffeehouses sprang up in Greenwich Village in the late 1940s, but the beats weren’t averse to hanging out in cafeterias either — their “Paris sidewalk restaurant thing of the time.” When coffeehouses began levying cover charges for performances, beatniks tended to drop out of them too. The heyday of the coffeehouse was the late 1950s into the early 1960s. Few did much cooking so they weren’t restaurants in the true sense, but many of them offered light food such as salami sandwiches (on exotic Italian bread) and cheesecake, along with “Espresso Romano,” the most expensive coffee ever seen in the U.S. up til then. Of course the charge for coffee was more a rent payment than anything else since patrons sat around for hours while consuming very little. Other then-unfamiliar food offerings included cannolis at La Gabbia (The Birdcage) in Queens, Swiss cuisine at Alberto’s in Westwood CA, Irish stew at Coffee ’n’ Confusion in D.C., les fromages at Café Oblique in Chicago, “Suffering Bastard Sundaes” at The Bizarre in Greenwich Village, and snacks such as chocolate-covered ants and caterpillars at the Green Spider in Denver.

The heyday of the coffeehouse was the late 1950s into the early 1960s. Few did much cooking so they weren’t restaurants in the true sense, but many of them offered light food such as salami sandwiches (on exotic Italian bread) and cheesecake, along with “Espresso Romano,” the most expensive coffee ever seen in the U.S. up til then. Of course the charge for coffee was more a rent payment than anything else since patrons sat around for hours while consuming very little. Other then-unfamiliar food offerings included cannolis at La Gabbia (The Birdcage) in Queens, Swiss cuisine at Alberto’s in Westwood CA, Irish stew at Coffee ’n’ Confusion in D.C., les fromages at Café Oblique in Chicago, “Suffering Bastard Sundaes” at The Bizarre in Greenwich Village, and snacks such as chocolate-covered ants and caterpillars at the Green Spider in Denver.

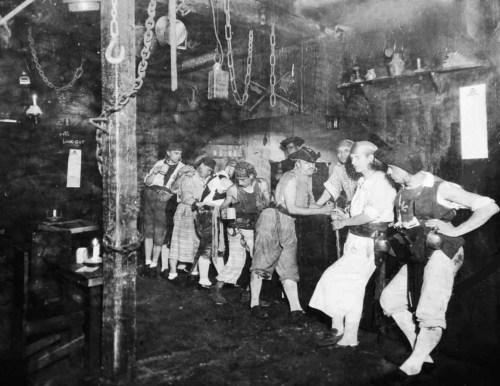

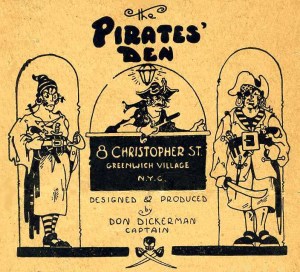

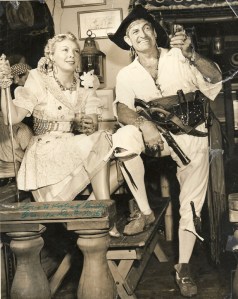

Don Dickerman was obsessed with pirates. He took every opportunity to portray himself as one, beginning with a high school pirate band. As an art student in the teens he dressed in pirate garb for Greenwich Village costume balls. Throughout his life he collected antique pirate maps, cutlasses, blunderbuses, and cannon. His Greenwich Village nightclub restaurant, The Pirates’ Den, where colorfully outfitted servers staged mock battles for guests, became nationally known and made him a minor celebrity.

Don Dickerman was obsessed with pirates. He took every opportunity to portray himself as one, beginning with a high school pirate band. As an art student in the teens he dressed in pirate garb for Greenwich Village costume balls. Throughout his life he collected antique pirate maps, cutlasses, blunderbuses, and cannon. His Greenwich Village nightclub restaurant, The Pirates’ Den, where colorfully outfitted servers staged mock battles for guests, became nationally known and made him a minor celebrity.

Over time he ran five clubs and restaurants in New York City. After failing to make a living as a toy designer and children’s book illustrator, he opened a tea room in the Village primarily as a place to display his hand-painted toys. It became popular, expanded, and around 1917 he transformed it into a make-believe pirates’ lair where guests entered through a dark, moldy basement. Its fame began to grow, particularly after 1921 when Douglas Fairbanks recreated its atmospheric interior for his movie The Nut. He also ran the Blue Horse (pictured), the Heigh-Ho (where Rudy Vallee got his start), Daffydill (financed by Vallee), and the County Fair.

Over time he ran five clubs and restaurants in New York City. After failing to make a living as a toy designer and children’s book illustrator, he opened a tea room in the Village primarily as a place to display his hand-painted toys. It became popular, expanded, and around 1917 he transformed it into a make-believe pirates’ lair where guests entered through a dark, moldy basement. Its fame began to grow, particularly after 1921 when Douglas Fairbanks recreated its atmospheric interior for his movie The Nut. He also ran the Blue Horse (pictured), the Heigh-Ho (where Rudy Vallee got his start), Daffydill (financed by Vallee), and the County Fair. On a Blue Horse menu of the 1920s Don’s mother is listed as manager. Among the dishes featured at this jazz club restaurant were Golden Buck, Chicken a la King, Tomato Wiggle, and Tomato Caprice. Drinks (non-alcoholic) included Pink Goat’s Delight and Blue Horse’s Neck. Ice cream specials also bore whimsical names such as Green Goose Island and Mr. Bogg’s Castle. At The Pirates’ Den a beefsteak dinner cost a hefty $1.25. Also on the menu were chicken salad, sandwiches, hot dogs, and an ice cream concoction called Bozo’s Delight. A critic in 1921 concluded that, based on the sky-high menu tariffs and the “punk food,” customers there really were at the mercy of genuine pirates.

On a Blue Horse menu of the 1920s Don’s mother is listed as manager. Among the dishes featured at this jazz club restaurant were Golden Buck, Chicken a la King, Tomato Wiggle, and Tomato Caprice. Drinks (non-alcoholic) included Pink Goat’s Delight and Blue Horse’s Neck. Ice cream specials also bore whimsical names such as Green Goose Island and Mr. Bogg’s Castle. At The Pirates’ Den a beefsteak dinner cost a hefty $1.25. Also on the menu were chicken salad, sandwiches, hot dogs, and an ice cream concoction called Bozo’s Delight. A critic in 1921 concluded that, based on the sky-high menu tariffs and the “punk food,” customers there really were at the mercy of genuine pirates.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.