Sometimes I feel the need to focus on ridiculousness in restaurants, maybe because I run across so many instances of it when I’m meandering through old sources. Lately I’ve been exploring franchising and have encountered numerous silly concepts expressed in the names of chains. Many businesses across the country adopted “Mister” or “Mr.” as part of their names, and this seems to have been particularly true of restaurant chains. [For now, I’m calling all of them Mister.]

There are also scores of restaurants with names such as Mister Mike’s or Mister T’s, but those are usually not part of franchise chains and the letter or nickname refers to an actual person, usually the owner, who may be known by that name in real life. I’m not including those here.

I’m more interested in the Misters that are not named for actual humans. At least I’m hoping that there is no real-life Mister Beef, Bun, Burger, Chicken, Drumstick, Fifteen, Hambone, Hamwich, Hofbrau, Pancake, Quick, Sandwich, Sirloin, Softee, Steak, Swiss, or Taco.

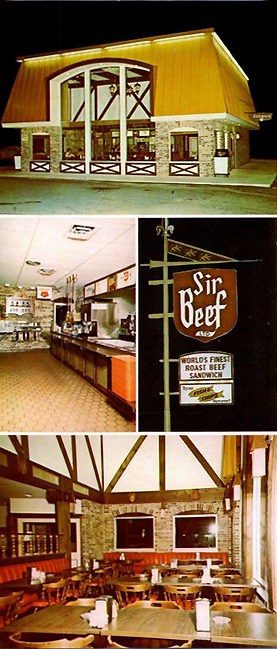

There were also Sir chains, such as Sir Beef, plus Kings and Senors. Were they in their own way an expression of multiculturalism? Being “continental,” Sir Beef was classier than most of the Misters.

For quite a while I believed there could be no Mister Chicken. That seemed obvious to me – who wants to be called a chicken? But then it occurred to me that I should do a little more research. I was proven wrong. Maybe I shouldn’t be surprised. Surrounding the logo shown here were the words: Home of America’s Best Barbecue Chicken Since 1966!” Although there were restaurants by the same name in Rockford IL and Atlanta GA, I don’t know if they were related.

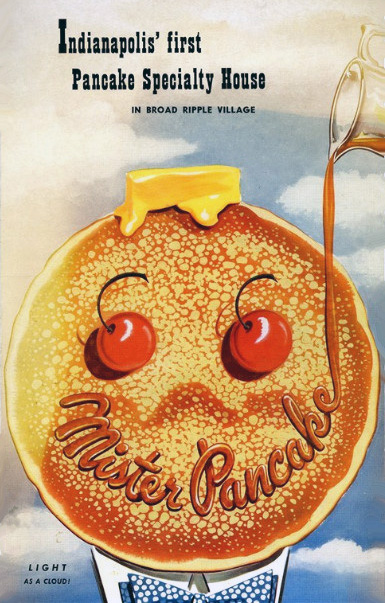

I find Mister Pancake’s face somehow threatening, but never mind that – he was a hit in his hometown of Indianapolis. He came into the world there in 1959, but I don’t know if he appeared anywhere else.

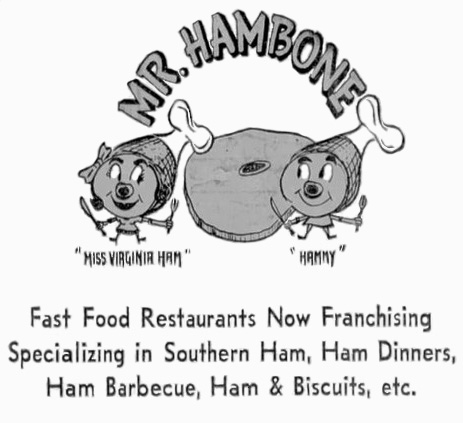

I especially like the logos that attempt to humanize food, particularly unlikely items such as hambones. Sadly for him and his girlfriend, Mister Hambone International – aka Hammy — really didn’t catch on. Starting out in Virginia in 1969, he opened at least one place in North Carolina, but nothing, I think, internationally.

Mister Softee with his natty bow tie, born in New Jersey, was mainly peddled out of ice cream trucks, but there were also restaurants of the same name that served hamburgers, steaks, hot dogs, fish, etc., along with the creamy guy. In 1967 a mobile franchise cost $2,500 while a restaurant was ten times that, which may account for why there were then 1,600 trucks — even as far off as the French West Indies — but only 5 restaurants. Overall, Mister Softee, like Mister Steak, had a more successful life than most of the Misters.

Mister Drumstick, born in Atlanta, offered the World’s Best Fried Chicken. I can’t help but wonder why he is holding a hamburger rather than a chicken leg. Maybe it was because his franchise was sold in connection with Mister Sirloin, a roast beefery, as well as Mister Hamwich, a ham sandwich purveyor. So far I’ve found four Mister Drumsticks in Atlanta and a few in Illinois, Ohio, and Missouri. Nino’s Mister Drumstick in Sandusky OH looks more athletic than Atlanta’s, but of course he has the advantage of legs. Was he a go-go dancer in an earlier phase of his career?

I like the Drumsticks, but my favorites are Mister Bun and Mister Sandwich (of New York City!). They are so versatile. They can handle anything that goes between two slices of bread. I don’t know what Mister Sandwich looked like but Mister Bun was a strange one, with his extremely short legs, his six-guns, and his 10-gallon hat. I can’t really figure him out. Is he trying to compensate for being nothing but bread?

The three Florida creators of Mister Bun had high hopes in 1968 when they opened their first location in Palm Beach, with plans to add more outlets in Florida as well as a number of other states where investors were interested. They advertised for franchisees by telling them that Mister Bun featured “the eight most popular food items in this nation.” It was true that Mister Bun could hold almost anything, so they settled on roast beef, cold cuts, roast pork, frankfurters and fish, accompanied by french fries and onion rings, and washed down with a range of beverages, including beer. Alas, Mister Bun had a rather unhappy life, experiencing little growth, abandonment by his primary creator, and time in court.

Females seemed to stay out of the game, so there are no Mrs. Buns, Mrs. Beefs, Mrs. Tacos . . . or Miss Steaks. Maybe theirs was the wiser course.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

People have strong feelings about their favorite dishes from restaurant chains. I am thankful to all those who poured their hearts out on the subject on Jane & Michael Stern’s ever-fascinating Roadfood forums. I have excerpted the following wistful memories from “Long-gone regional franchises” which took on a life of its own and ran for years. After each snippet is the pertinent chain restaurant.

People have strong feelings about their favorite dishes from restaurant chains. I am thankful to all those who poured their hearts out on the subject on Jane & Michael Stern’s ever-fascinating Roadfood forums. I have excerpted the following wistful memories from “Long-gone regional franchises” which took on a life of its own and ran for years. After each snippet is the pertinent chain restaurant. — The Cheese Frenchies were unique. [King’s Food Host]

— The Cheese Frenchies were unique. [King’s Food Host] — Pickles, diced onion, relish, mustard, ketchup and mayo were all available. [25 Cent Hamburger]

— Pickles, diced onion, relish, mustard, ketchup and mayo were all available. [25 Cent Hamburger] In the late 19th century owners of large popular-price restaurants began to look for ways to cut costs and eliminate waiters. The times were hospitable to mechanical solutions and in 1902 automatic restaurants opened in Philadelphia (pictured below) and New York. In both cities, a clever coin-operated set-up – and a name – were imported from

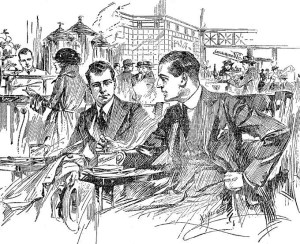

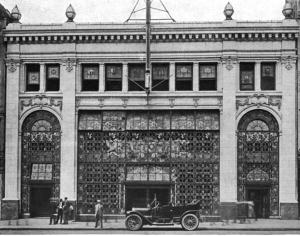

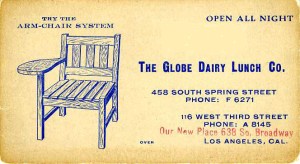

In the late 19th century owners of large popular-price restaurants began to look for ways to cut costs and eliminate waiters. The times were hospitable to mechanical solutions and in 1902 automatic restaurants opened in Philadelphia (pictured below) and New York. In both cities, a clever coin-operated set-up – and a name – were imported from  The Automat in NYC was owned by James Harcombe, who in the 1890s had acquired Sutherland’s, one of the city’s old landmark restaurants located on Liberty Street. The Harcombe Restaurant Company’s Automat was at 830 Broadway, near Union Square. Reportedly costing more than $75,000 to install, it was a marvel of invention decorated with inlaid mirror, richly colored woods, and German proverbs. It served forth sandwiches and soups, dishes such as fish chowder and

The Automat in NYC was owned by James Harcombe, who in the 1890s had acquired Sutherland’s, one of the city’s old landmark restaurants located on Liberty Street. The Harcombe Restaurant Company’s Automat was at 830 Broadway, near Union Square. Reportedly costing more than $75,000 to install, it was a marvel of invention decorated with inlaid mirror, richly colored woods, and German proverbs. It served forth sandwiches and soups, dishes such as fish chowder and  Undeterred by the first Automat’s fate, Horn & Hardart moved into New York in 1912, opening an Automat of their own manufacture at Broadway and 46th Street (pictured). It turned out that New Yorkers did indeed use slugs, especially in 1935 when 219,000 were inserted into H&H slots. But despite this, the automatic restaurant prospered, expanded, and became a New York institution. By 1918 there were nearly 50 Automats in the two major cities, and eventually a few in Boston. Horn & Hardart tried Automats in Chicago in the 1920s but they were a failure. On an inspection tour in Chicago, Joseph Horn noted problems such as weak coffee, “figs not right,” and “lem. meringue very bad.”

Undeterred by the first Automat’s fate, Horn & Hardart moved into New York in 1912, opening an Automat of their own manufacture at Broadway and 46th Street (pictured). It turned out that New Yorkers did indeed use slugs, especially in 1935 when 219,000 were inserted into H&H slots. But despite this, the automatic restaurant prospered, expanded, and became a New York institution. By 1918 there were nearly 50 Automats in the two major cities, and eventually a few in Boston. Horn & Hardart tried Automats in Chicago in the 1920s but they were a failure. On an inspection tour in Chicago, Joseph Horn noted problems such as weak coffee, “figs not right,” and “lem. meringue very bad.” The Automats hit their peak in the mid-20th century. Slugs aside, the Depression years were better for business than the wealthier 1960s and 1970s when some units were converted to Burger Kings. In 1933 H&H hired Francis Bourdon, the French chef at the Sherry Netherland (fellow chefs called him “L’Escoffier des Automats”). In 1969 Philadelphia’s first Automat closed, being declared “a museum piece, inefficient and slow, in a computerized world.” That left two in Philadelphia and eight in NYC. The last New York Automat, at East 42nd and 3rd Ave, closed in 1991.

The Automats hit their peak in the mid-20th century. Slugs aside, the Depression years were better for business than the wealthier 1960s and 1970s when some units were converted to Burger Kings. In 1933 H&H hired Francis Bourdon, the French chef at the Sherry Netherland (fellow chefs called him “L’Escoffier des Automats”). In 1969 Philadelphia’s first Automat closed, being declared “a museum piece, inefficient and slow, in a computerized world.” That left two in Philadelphia and eight in NYC. The last New York Automat, at East 42nd and 3rd Ave, closed in 1991.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.