By the 1880s Anthony E. Faust had established quite a culinary empire in St. Louis. He ran a Café and Oyster House downtown on Broadway which had a nationwide reputation. Since 1878 it had featured rooftop dining, uncommon in the U.S. then. From his adjoining “Fulton Market” he also retailed and wholesaled “Faust’s Own” oysters and other delicacies such as truffles, soy sauce, and curry powder which he shipped to Southwestern and Western states. His Faust label beer, made for him by the Anheuser brewery, was also sold in the West.

By the 1880s Anthony E. Faust had established quite a culinary empire in St. Louis. He ran a Café and Oyster House downtown on Broadway which had a nationwide reputation. Since 1878 it had featured rooftop dining, uncommon in the U.S. then. From his adjoining “Fulton Market” he also retailed and wholesaled “Faust’s Own” oysters and other delicacies such as truffles, soy sauce, and curry powder which he shipped to Southwestern and Western states. His Faust label beer, made for him by the Anheuser brewery, was also sold in the West.

He didn’t start out in the food business but as an ornamental plasterer who immigrated from the Prussian province of Westphalia at age 17. After being accidentally shot while watching a parade, he gave up his trade and decided to open a café in 1865.

Obviously he had a knack for the new business. And it helped that St. Louis was a booming hub of shipping and commerce positioning itself to dominate commerce with the West. His closeness to the Adolphus Busch family of beer fame was undoubtedly another asset. In 1886 Tony opened a second restaurant in a huge new Exposition Building on Olive Street between 13th and 14th which hosted conventions of architects, music teachers, fraternal organizations, and the Democratic National Convention of 1888.

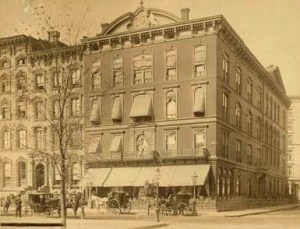

In the late 1880s he razed his restaurant and replaced it with a finer building. With an interior of carved mahogany woodwork, a tapestried ceiling, and an elaborate mosaic tile floor, the restaurant catered to the fashionable after-theater crowd. At some point, perhaps in 1889, a second story was added, eliminating the rooftop garden (above image, ca. 1906).

Success seemed to mean Tony could do as he wished. Caught serving prairie chickens out of season (under the frankly fraudulent name “Virginia owls”), he freely confessed and flippantly said he’d pay the fine or “break rock” if need be. When the Republican National Convention was held in St. Louis in 1896 he claimed his staff would not prepare or serve meals for Afro-American delegates. Even after the convention’s managers offered to hire a space, furnish stoves, and buy provisions to feed the black delegates if Faust would oversee the work, he absolutely refused to do it. Period.

In preparation for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair (the Louisiana Purchase Exposition), Faust joined half a dozen of St. Louis’s top restaurateurs in a trust, the St. Louis Catering Company, probably designed to buy in large quantities and possibly to set prices too. Faust went into partnership with New York’s Lüchow’s to create a Tyrolean Alps Restaurant at the Fair which seated 5,000 diners and featured costumed singers (pictured). It represented brewers’ interests as well, leading one observer to joke that the enormous beer hall should have been named “Budweiser Alps.” According to the Fair’s Official Program there was also a Faust restaurant in the Fair’s west pavilion on Art Hill.

In preparation for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair (the Louisiana Purchase Exposition), Faust joined half a dozen of St. Louis’s top restaurateurs in a trust, the St. Louis Catering Company, probably designed to buy in large quantities and possibly to set prices too. Faust went into partnership with New York’s Lüchow’s to create a Tyrolean Alps Restaurant at the Fair which seated 5,000 diners and featured costumed singers (pictured). It represented brewers’ interests as well, leading one observer to joke that the enormous beer hall should have been named “Budweiser Alps.” According to the Fair’s Official Program there was also a Faust restaurant in the Fair’s west pavilion on Art Hill.

At the time Tony Sr. died in 1906 the Faust empire included a second Fulton Market location, and another Faust restaurant in the Delmar Gardens amusement park in University City managed by his son Tony R. Faust. Like many a successful businessman in the Midwest, Tony R. went to NYC to see about opening a branch there. There was a Faust restaurant in NYC’s Columbus Circle in 1908 (pictured), but I am not certain whether this belonged to the St. Louis Fausts. In 1911 Tony Jr. was declared insane. After that his older brother Edward, an executive of Anheuser-Busch who was married to a daughter of Adolphus Busch, took over the restaurants and markets. The downtown restaurants in St. Louis and NYC, and probably the others as well, closed in 1915 and 1916, casualties of looming Prohibition.

At the time Tony Sr. died in 1906 the Faust empire included a second Fulton Market location, and another Faust restaurant in the Delmar Gardens amusement park in University City managed by his son Tony R. Faust. Like many a successful businessman in the Midwest, Tony R. went to NYC to see about opening a branch there. There was a Faust restaurant in NYC’s Columbus Circle in 1908 (pictured), but I am not certain whether this belonged to the St. Louis Fausts. In 1911 Tony Jr. was declared insane. After that his older brother Edward, an executive of Anheuser-Busch who was married to a daughter of Adolphus Busch, took over the restaurants and markets. The downtown restaurants in St. Louis and NYC, and probably the others as well, closed in 1915 and 1916, casualties of looming Prohibition.

© Jan Whitaker, 2010

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.