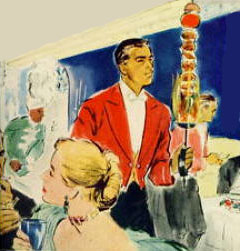

When I was researching my last post on knights-and-castles restaurant themes I discovered that this kind of theatrical decor was often complemented by flamboyant food presentation, especially the kind that mixes weaponry and meat. Specifically sticking meat on a sword, setting it aflame, and rushing it toward your guests.

When I was researching my last post on knights-and-castles restaurant themes I discovered that this kind of theatrical decor was often complemented by flamboyant food presentation, especially the kind that mixes weaponry and meat. Specifically sticking meat on a sword, setting it aflame, and rushing it toward your guests.

If you like that and had been looking for a fun night out in the vicinity of Reno, Nevada, in 1960, you might have turned up at The Lancer, “home of the flaming sword” and Glen Relfson at the organ. The Lancer’s advertisement showed a knight charging forward on his horse with lance in hand — yet, disappointingly, the food came on an everyday sword. Why not a lance?

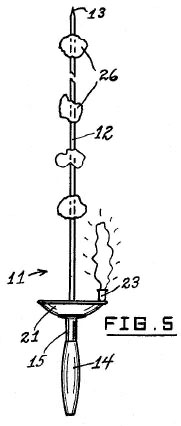

I’ve searched U.S. patents and the reason why meat was not served on a lance is because no one thought to invent a lance — or a gun, why not? — that could go on the grill loaded up with shish kebab. But they did invent several very practical-minded swords, either with detachable handles (permitting the handle to stay cool while the skewered meat cooks on the grill), or with the hand protector turned upward to catch dripping grease when the sword is held upright (pictured). As the patentees methodically argued, these features are important to restaurant managers.

Many municipalities have enacted fire regulations that do not permit restaurant employees to carry flaming objects across a room. This has cut down the number of restaurants that offer this service today as compared to the peak in the mid-20th century and through the 1970s.

Many municipalities have enacted fire regulations that do not permit restaurant employees to carry flaming objects across a room. This has cut down the number of restaurants that offer this service today as compared to the peak in the mid-20th century and through the 1970s.

It’s possible the custom began in restaurants with Russian themes. In the 1930s there was a place in San Francisco called the Moscow Café which had Cossack dancing, entertainment with flaming swords, and a specialty of flaming Beef Stroganoff. (Presumably the sour cream was added after the flames subsided.) Los Angeles’ Bublichki Russian Café also offered beef on flaming swords in the 1950s. And a patent was granted in 1965 for an item called a “shashlik sword.”

How does the flame work? I always wondered. As a patent applicant explained, “this is usually accomplished through igniting, immediately before serving, a piece of cotton which, first dipped in alcohol, is wrapped around the base of the sword near the hilt thereof.” However if you adopted another design you could have a wick holder built into the grease drip cup “so that when the skewer is carried in an upright position with cooked meats or other food articles impaled thereon, the wick, previously soaked with rum or brandy, may be ignited, providing a dramatic torch-like effect as the skewer is carried from the kitchen to the table.” Quite frankly, that would be my preferred sword because I like the way it catches grease and eliminates cotton wads thereon.

You may be thinking that only corny restaurants in mini-malls featured food on swords but you’d be wrong. For instance, the menu at NYC’s Forum of the Twelve Caesars in the early 1960s included, perhaps for lighter appetites, Wild Boar Marinated and Served on the Flaming Short Sword. And, starting in the 1940s, flaming swords were practically synonymous with the fabulously funky Pump Room in Chicago’s Ambassador East Hotel. The Pump Room’s manager Ernie Byfield laughingly referred to the action there, consisting of costumed waiters weaving through crowds of guests with “flaming gobbets of lamb,” as being “like Halloween in Hell.” I don’t believe anyone was immolated.

You may be thinking that only corny restaurants in mini-malls featured food on swords but you’d be wrong. For instance, the menu at NYC’s Forum of the Twelve Caesars in the early 1960s included, perhaps for lighter appetites, Wild Boar Marinated and Served on the Flaming Short Sword. And, starting in the 1940s, flaming swords were practically synonymous with the fabulously funky Pump Room in Chicago’s Ambassador East Hotel. The Pump Room’s manager Ernie Byfield laughingly referred to the action there, consisting of costumed waiters weaving through crowds of guests with “flaming gobbets of lamb,” as being “like Halloween in Hell.” I don’t believe anyone was immolated.

© Jan Whitaker, 2011

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.