As far back as the early 19th century students have made up a notable segment of restaurant clientele. They have played a significant historical role both in supporting the growth of restaurants and in shaping the eating habits of Americans.

As far back as the early 19th century students have made up a notable segment of restaurant clientele. They have played a significant historical role both in supporting the growth of restaurants and in shaping the eating habits of Americans.

In the 1800s some restaurants located near colleges specifically catered to students, alumni, and college faculty and staff. As incomparable caterer Othello Pollard of Cambridge MA noted in an 1802 advertisement, “Harvard flourishes and Othello lives.” In NYC in the 1840s poor divinity students could be found at the “sixpenny” eating house called Sweeny’s downing slices of roast beef, clam soup, pickles, and bread and cheese.

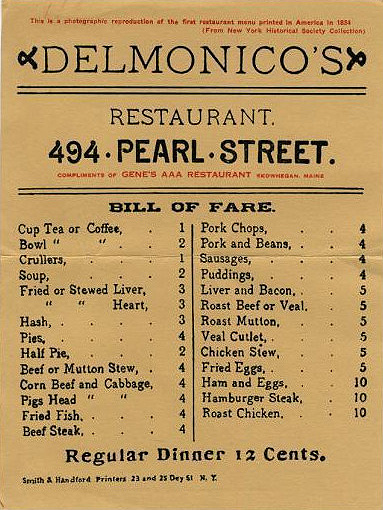

One of the penny-pinching patrons at Sweeny’s was Lyman Abbot, an NYU student who later became a noted theologian. Each month when he got his allowance he splurged on dinner at Delmonico’s, but as his money ran low at the end of the month he subsisted on Sweeny’s wheat cakes.

Restaurants clustered around colleges often billed themselves as “student headquarters” and supplied not only food, but entertainment in the form of billiards and supplies such as books and stationery. Hoadley’s, “Hoad’s” to Harvard students, also rented velocipedes in the 1860s. Restaurants around Yale sold weekly meal tickets, hosted private parties, and delivered midnight snacks – “spreads” – to students’ rooms [pictured: midnight “lunch” near Penn State College, 1905]. Billy Park’s chop house in Boston was a hot spot for Harvard students following athletic events. Big-spending students could enjoy the luxurious “sports bar” eateries of their day at places such as Newman’s College Inn in Oakland CA. When it opened ca. 1910 it was decorated with college pendants and tapestries depicting scenes in a man’s life from college to middle age. Murals pictured various college sports while chandeliers were fashioned out of copper and glass footballs.

Restaurants clustered around colleges often billed themselves as “student headquarters” and supplied not only food, but entertainment in the form of billiards and supplies such as books and stationery. Hoadley’s, “Hoad’s” to Harvard students, also rented velocipedes in the 1860s. Restaurants around Yale sold weekly meal tickets, hosted private parties, and delivered midnight snacks – “spreads” – to students’ rooms [pictured: midnight “lunch” near Penn State College, 1905]. Billy Park’s chop house in Boston was a hot spot for Harvard students following athletic events. Big-spending students could enjoy the luxurious “sports bar” eateries of their day at places such as Newman’s College Inn in Oakland CA. When it opened ca. 1910 it was decorated with college pendants and tapestries depicting scenes in a man’s life from college to middle age. Murals pictured various college sports while chandeliers were fashioned out of copper and glass footballs.

Alums regularly gravitated back to their college haunts to relive their youth. “Papa” confessed to his daughter on a 1906 postcard of the “Famous Dutch Kitchen, one of the most noted student resorts in the country” near Cornell University, that he planned to eat there before returning home. “I am going to be a college sport for just two days. Big crowd in town. Slept at Fraternity house last night,” he wrote.

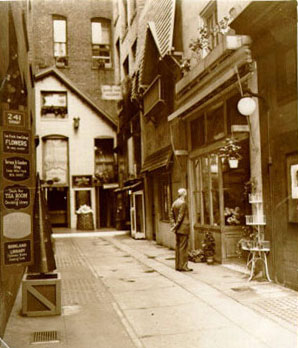

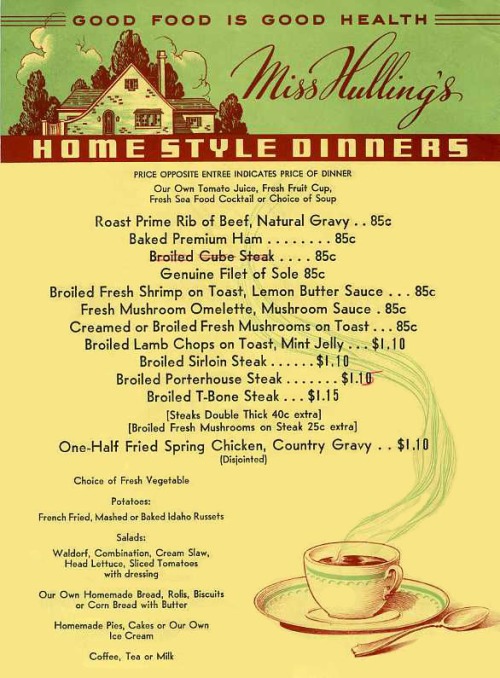

Many 19th-century eating places were restricted to male guests, but students at women’s colleges were supplied with tea rooms in the early 20th century [pictured: Brown Betty tea room near Shorter College]. Near the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Almira Lovell’s University Tea Room offered teas along with dressmakers’ supplies and college souvenirs in 1903. Around the same time Smith students could often be found curled up on window seats eating popcorn at the Copper Kettle in Northampton. Well into the 1920s being stricken from a college’s approved list was the kiss of death for tea rooms and other eating places that depended upon patronage of women students. Such was the fate of the Rose Tree Inn in Northampton as well as a tea room near Connecticut College.

Many 19th-century eating places were restricted to male guests, but students at women’s colleges were supplied with tea rooms in the early 20th century [pictured: Brown Betty tea room near Shorter College]. Near the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Almira Lovell’s University Tea Room offered teas along with dressmakers’ supplies and college souvenirs in 1903. Around the same time Smith students could often be found curled up on window seats eating popcorn at the Copper Kettle in Northampton. Well into the 1920s being stricken from a college’s approved list was the kiss of death for tea rooms and other eating places that depended upon patronage of women students. Such was the fate of the Rose Tree Inn in Northampton as well as a tea room near Connecticut College.

Students dearly appreciated places to “hang out” because well into the 20th century colleges and universities provided few dormitories and many students lived in rented rooms off campus. Plus, as recent research into Depression-era student life at the State Teachers College in Normal IL has shown, living off campus permitted poor students to economize on food expenses.

Students dearly appreciated places to “hang out” because well into the 20th century colleges and universities provided few dormitories and many students lived in rented rooms off campus. Plus, as recent research into Depression-era student life at the State Teachers College in Normal IL has shown, living off campus permitted poor students to economize on food expenses.

College students were prominent among the artsy, “bohemian” restaurant-going crowd. In the late 19th century, when lower Manhattan was filled with schools, students congregated around Washington Square. San Francisco’s art students loved Italian dinners at Sanguinetti’s. In Chicago in the 1920s students met at the Wind Blew Inn. In later decades student beatniks would flock to coffee houses, which in turn were succeeded by hippie hangouts. In 1960 the NYT reported that in one Greenwich Village student café an undercover government agent was asked blandly, “Do you want coffee or peyote?”

It’s harder to track high school students, at least until the 40s and 50s when their consumption of snack foods such as hamburgers, sodas, and pizzas became noticeable. Like college students before them they tended to favor informal meals eaten at odd hours of the day and night.

It’s harder to track high school students, at least until the 40s and 50s when their consumption of snack foods such as hamburgers, sodas, and pizzas became noticeable. Like college students before them they tended to favor informal meals eaten at odd hours of the day and night.

It would be interesting to calculate how many of the post-WWII fast food restaurant chains opened their early units near high schools and colleges. This was certainly true of King’s Food Host, Steak n Shake, and the Parkmoor drive-ins. I have no doubt there were many others.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.