As those of us who collect menus know, people are more likely to preserve menus from restaurants related to memorable occasions than those from ordinary, everyday eating places. As a result, there are more menus in the ephemera market that come from famous restaurants, voyages on ships, and banquets than from humble eateries. I tend to concentrate on the latter group, but once in a while I will buy a banquet menu that interests me.

As those of us who collect menus know, people are more likely to preserve menus from restaurants related to memorable occasions than those from ordinary, everyday eating places. As a result, there are more menus in the ephemera market that come from famous restaurants, voyages on ships, and banquets than from humble eateries. I tend to concentrate on the latter group, but once in a while I will buy a banquet menu that interests me.

I particularly like ones that are from professional and business trade groups, unions, and organizations such as the three shown here. Even better if they have a humorous slant, as is surprisingly often the case.

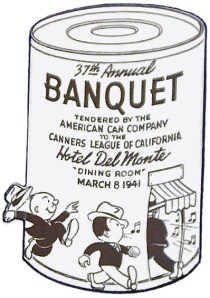

The 1941 menu at the top, from a dinner presented by the American Can Company to a California trade group at the Hotel Del Monte, shares something in common with the dinner given for the Golden Jubilee of the Oakland Typographical Union in 1936. The site of the canners’ banquet, the Hotel Del Monte in Monterey CA, like the union’s locale, the Oak Knoll Country Club in Oakland CA, was soon to become a property of the U.S. Navy. The canners may have enjoyed one of the last banquets held at the historic hotel, originally opened in 1880, but rebuilt in the 1920s after a disastrous fire.

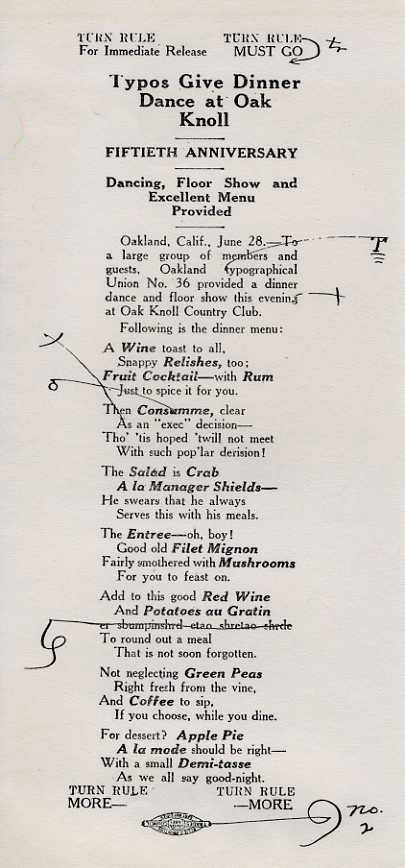

The Oakland “Typos’” menu is one of my favorites because of its design as a proof adorned with proofreader’s corrections. It is not only clever but reminds me of a job I once had back in the days of linotype when I marked up proofs using the very same marks indicating lines to be deleted and transferred, as well as misspelled words, broken type, etc.

The Oakland “Typos’” menu is one of my favorites because of its design as a proof adorned with proofreader’s corrections. It is not only clever but reminds me of a job I once had back in the days of linotype when I marked up proofs using the very same marks indicating lines to be deleted and transferred, as well as misspelled words, broken type, etc.

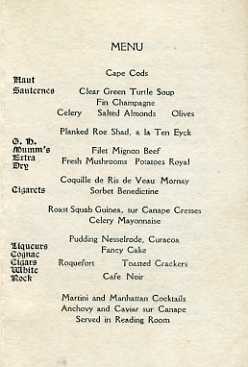

The Legislative Correspondents’ Association, which still exists, held its first dinner in 1900, so this menu is from its tenth, held in Albany at the Hotel Ten Eyck – on April Fools Day, 1909. Throughout it is filled with wry commentary and comical rules for the banquet governing issues around table companions and drinking. Judging from the menu, I’d think everyone got plenty to drink. Not only is the dinner accompanied by wine, champagne, liqueur, and cognac, it’s topped off with cocktails. Whoa.

The Legislative Correspondents’ Association, which still exists, held its first dinner in 1900, so this menu is from its tenth, held in Albany at the Hotel Ten Eyck – on April Fools Day, 1909. Throughout it is filled with wry commentary and comical rules for the banquet governing issues around table companions and drinking. Judging from the menu, I’d think everyone got plenty to drink. Not only is the dinner accompanied by wine, champagne, liqueur, and cognac, it’s topped off with cocktails. Whoa.

I don’t know if the canners were served canned food at their banquet, but I’d say that the journalists undoubtedly enjoyed the finest cuisine of the three groups.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.