My last post about a restaurant designer who applied psychology to his work inspired me to look further into this subject.

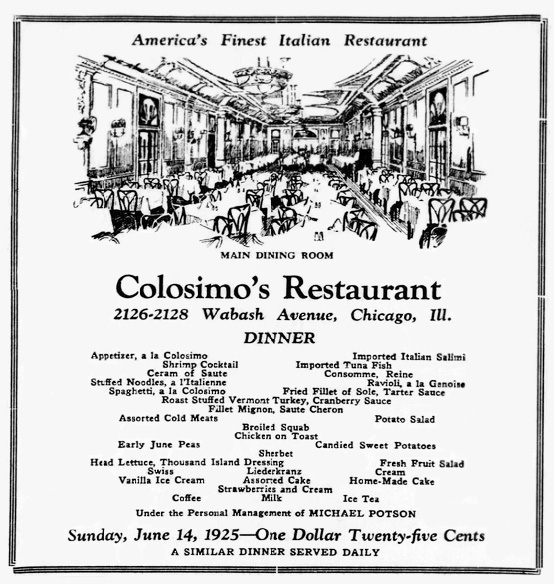

I discovered that when the restaurant world was experiencing hard times there was a turn toward psychology, though of course that wasn’t the only inspiration. In the 1920s, when liquor sales became illegal, expensive restaurants were inspired to look harder for ways to please their guests. A proprietor whose famous eating place had to close warned others that “What the restaurant loses in the revenue from wines and liquors it must make up in psychology.” Evidently in his case, this realization came too late.

Canny cafeteria operators, though never dependent upon liquor sales, were already using psychology on their guests in the 1920s. And as early as 1927 a psychology professor appeared at restaurant conventions to give attendees help in figuring out “What do people like and why?”

Psychology often veered into what I would call blatant manipulation, for instance in cafeterias. Cafeterias tried such things as enlarging trays so they looked empty unless the customer loaded up. They also placed desserts on eye-level shelves that were the first thing the hungry customer saw as they entered the cafeteria line.

In later years other manipulative ploys in everyday eating places would include uncomfortable seating and bright colors that shortened customers’ stays, as I have previously written about.

The Depression and WWII put a damper on psychology advising, but it returned in the 1950s. A strange example was a Hollywood therapist who made a practice of visiting a restaurant called The House of Murphy. He went table to table giving customers, many of them actors, his analyses of their psyches. I would not think they appreciated some of his insights, such as when he told Gary Cooper that he was a “withdrawn introvert.” As for dining, his verdict was that “A very large meal is an escape mechanism.” As he saw it, “The customer is gorging himself in order to have a sense of security and power.”

Other restaurant psychologists turned to writing columns for newspapers. Dr. George W. Crane, for instance, focused on sloppy waitresses who failed to meet his standards, that of a “glorified mother.” “And be sure to smile,” he advised them, “for this makes you a psychotherapist who helps the morale, appetite and even the digestion of lonely, moody and fearful souls.” All for 50 cents an hour?

By the 1970s restaurant psychology had taken leaps forward and was a tool of restaurant designers, beginning with interior and exterior design and assistance with restaurant concepts, naming, advertising, and public relations.

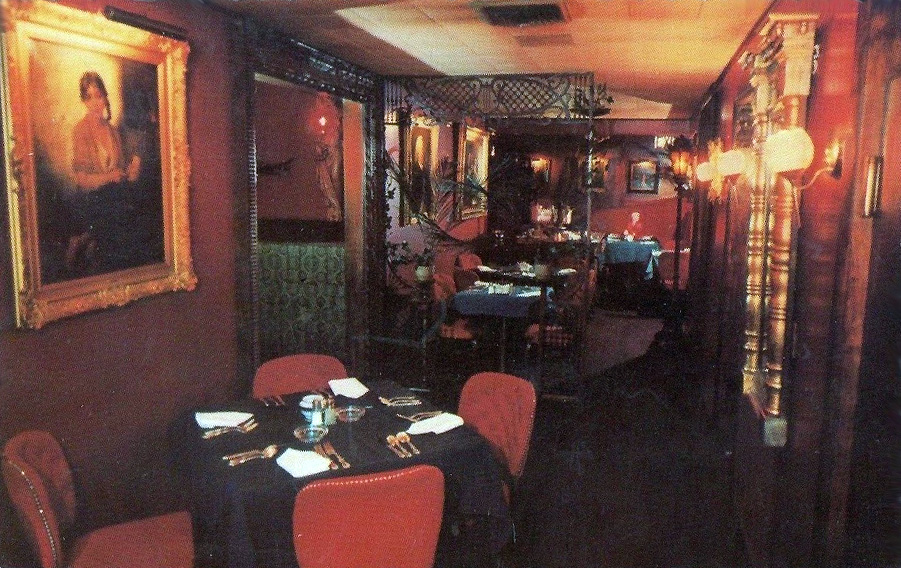

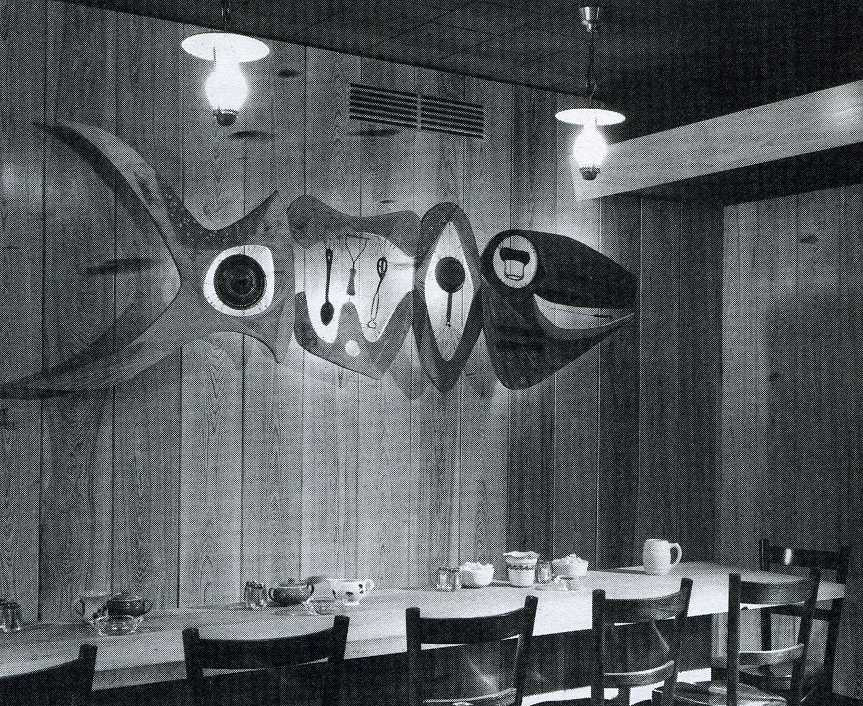

In 1977 David Stevens, then considered a leading restaurant designer, had a hand in the design of 100 restaurants, including fast food chains Hobo Jo, Humpty Dumpty, the Mediterranean in Honolulu, and a number of Bobby McGee’s, as well as the Mai Kai in Fort Lauderdale [shown below]. He believed a restaurant had to be in tune with the “emotional trend of the nation.” In 1977 he favored nature themes and booths to “give the public something to lean on” at a time of nationwide insecurity due to a weak economy. Though he declared that the rustic look was “out,” he admitted that heavy beams could sooth tension.

Another slant on booths came from a designing couple who proclaimed that they served as “a womb surrounding and hiding customers who don’t want to be seen, especially if they’re a little overweight.”

Plants were tricky according to some. In 1980, the part owners of Ruby Tuesday’s Emporium noted plants could be used very strategically. “If you’re aiming for college-age patrons,” they advised, “there should be floor plants.” On the other hand, young professionals liked hanging plants which they said, “denote a higher degree of sophistication.”

In 1983, restaurants had not recovered from the recession of the previous year. In Broward County, Florida, with its 2,600 restaurants, there was a high failure rate in the first year of the recession. Some restaurants sought help from an industrial psychologist who trained staffs in empathy with the customer, and taught them to how to handle uncomfortable situations.

The emphasis stayed on servers at the National Restaurant Association’s annual conference the following year. A psychology professor from Denver’s School of Hotel and Restaurant Management was on hand to instruct participants in their “real” business: not selling food and drink, but in fulfilling people’s needs. Servers were to smile, answer questions, and show interest in what the customer was ordering. They were to nod their heads, and say “I see“ and “uh-huh.”

Of course, by this time it was taken for granted that interior design was important. In 1984 some thought that the nation was “longing to return to simpler times.” In design this was frequently interpreted as early-American themes, barn siding, and huge beams.

But in Houston a design team had a very different interpretation. They preferred to give new restaurants a worn, slightly dirty, look. To achieve this they gave walls a few stains and planted handprints around light switch plates. Customers were to feel they didn’t have to be super careful, that spills were perfectly ok. The Atchafalaya River Café gave an aged look to the building formerly occupied by the Monument Inn. They covered part of the roof with battered tin, deliberately left paint splatters on the front window, and used old doors for the front, pasting them with bumper stickers, all in the belief “that tacky, comfortable design makes people happy.”

Why not a country theme? Well, as the designers of the Atchafalaya River Café liked to say: “Pastoral scenes are deadly to a good time in restaurants. Customers feel mother or grandmother is watching every move.”

Bringing another sense into play, noise became part of design in the 1980s. Designer Leonard Horowitz said in 1986 that at the Crab Shack in Miami, where diners smashed crabs with wooden paddles at their tables, “ear-splitting volume is one of the things that makes the Crab Shack so popular with many of its customers.” He thought it was because people “enjoy feeling like part of a party or performance.” He also noted that while noisy spaces felt festive they also encouraged quick turnover, which of course greatly enhanced profits in popular places.

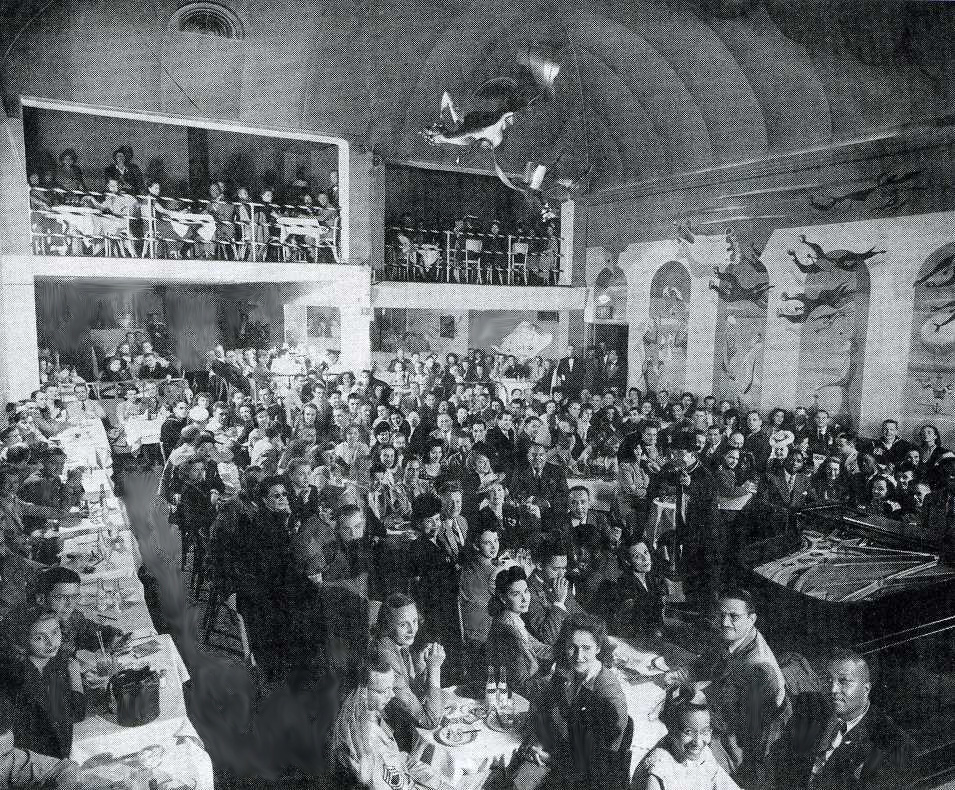

By the late 1990s, and very likely before that, having a professional designer versed in restaurant psychology was common, particularly in the case of restaurant chains. That was especially true in restaurants that aimed to entertain as well as to provide food. The word for this is “eatertainment” in recognition that food is only one reason that people patronize restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.