In the 19th century and much of the early 20th restaurant owners viewed women’s tastes as quite different than men’s.

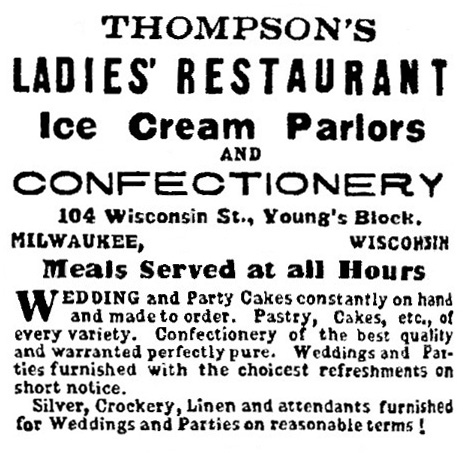

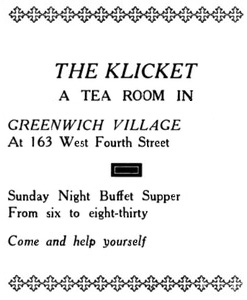

Women did not patronize restaurants to a great extent in the 19th century, but it seems when they did they preferred places that furnished ice cream, pastries, and cakes, not only for immediate consumption but also to order for the home. For instance, in 1865 in Milwaukee WI there was Thompson’s Ladies’ Restaurant, Ice Cream Parlor, and Confectionery which provided three meals a day plus Tea, along with Wedding and Party Cakes to order. [Advertisement shown below]

Such places were seemingly rare and I doubt that their customers included women of little means. In 1869, it was reported that poor working women frequented “coffee places” where they ordered simply bread or cake with coffee. But even these may have introduced the long-lasting idea that women were particularly fond of sweet foods.

I wonder if it was often the case that they made do with a simple sweet dish because that was all they could afford.

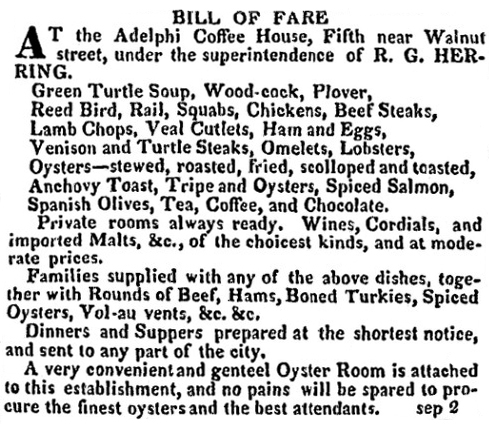

Of course, sweet dishes were not women’s only preferences if they could pay more. Oysters were also popular choices — as they were with men.

Commentary about women’s food preferences was sometimes insulting. The idea seemed to be firmly planted for decades and well into the 20th century that women were frivolous eaters while men chose real food. That would be repeated time and time again in books and newspaper stories. For instance:

1888, New York Tribune: In ladies restaurants a woman might order salad, ice cream, oyster patty, eclaire, cheese cake, “and perhaps one or two other varieties of whipped froth and baked wind.”

1894, Charles Ranhofer cookbook: “Should the menu be intended for a dinner including ladies, it must be composed of light, fancy dishes with a pretty dessert; if, on the contrary, it is intended for gentlemen alone, then it must be shorter and more substantial.”

1917, Housewives Magazine: a woman “expert” reported that men made “habitual food choices” while women “go by eye-appeal.” Typically, she explained, almost all men ate meat, while women preferred fruit salad, beans or macaroni, and cake and ice cream.

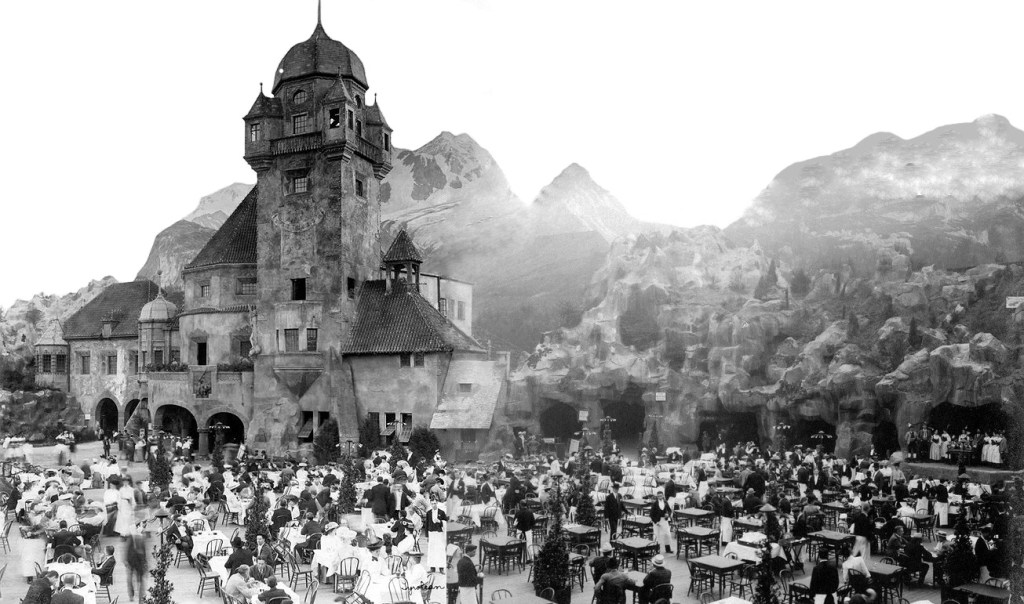

By the mid-1920s women were making up a larger proportion of restaurant goers than ever before, possibly as much as 60%. Pleasing them was becoming essential. The trade magazine Restaurant Management advised: “Many managers have not yet seen the light. If you doubt this watch the places that get the women’s trade. In the majority of cases these restaurants serve light, tasty foods in homelike surroundings and at a reasonable price “

But even as women’s patronage became important, there were still commentaries that were insulting. Eating habits were changing, possibly due in large part to Prohibition, leading the former proprietor of Keen’s Chop House in NYC to comment in 1931: “Formerly when a man took a lady to dinner he not only selected the restaurant, he took great pride in ordering a particularly choisi, well-balanced meal.” But, he said, it had become clear that now women “would rather have had the unholy hodgepodges you see them reveling in to-day.”

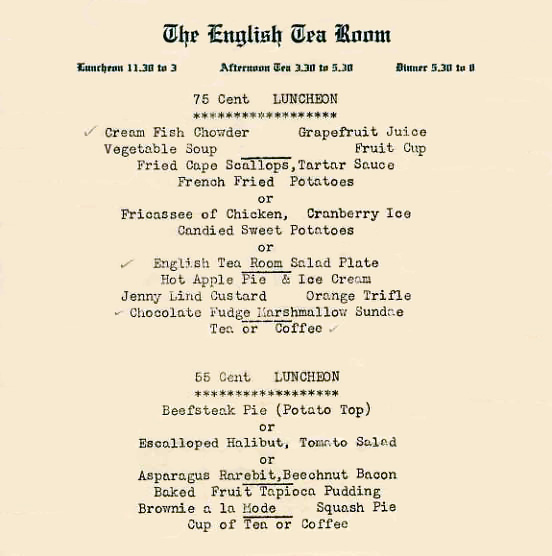

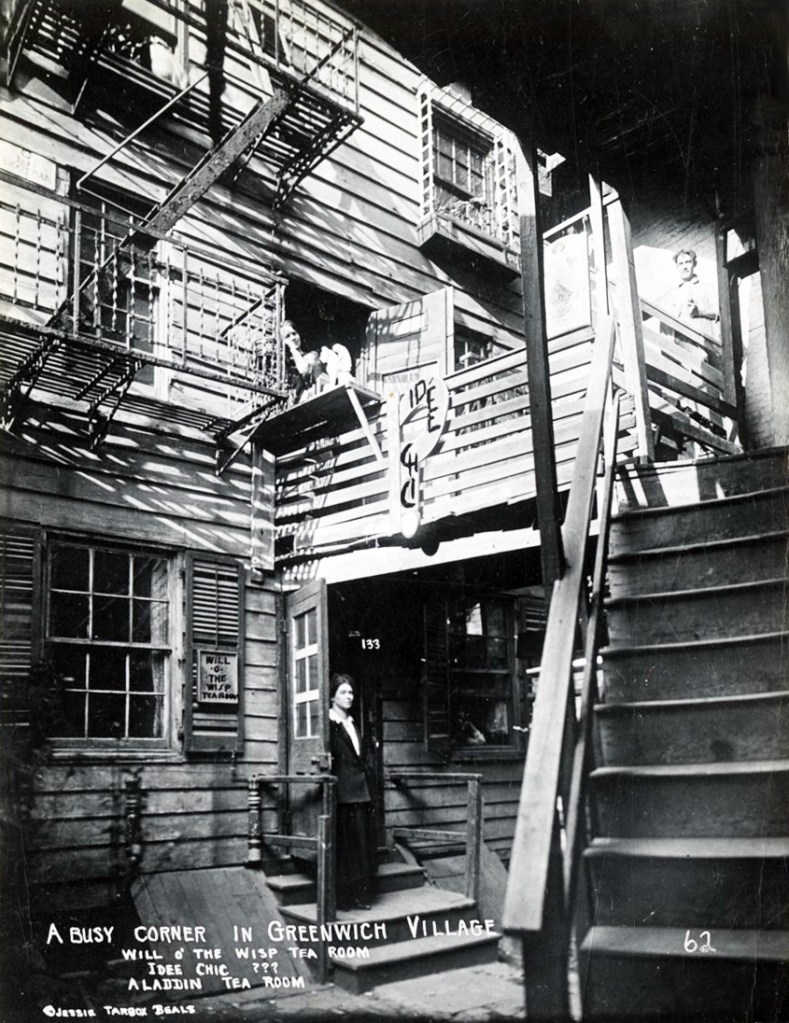

Even some women criticized women’s food choices. In 1937 a woman who had worked for major restaurant chains said that to succeed in the Depression tea room operators had to recognize that men wanted “real food” . . . not “Canary bird food.” [Above: Boston tea room’s “canary bird food.”]

Slowly, insults concerning women’s tastes died down, although differences in restaurant orders based on gender were still observed. In 1934 a woman tea room operator said that “The conventional woman’s taste runs to chicken patties, peas, and ice cream; men like steaks, French fried potatoes, and apple pie.”

Had differences largely disappeared by the 1950s? When I wrote an earlier post I thought that numbers of men still wanted what they regarded as he-man meals and that there were restaurants willing to cater to them.

Yes, a chef commented in 1952, there were those who still believed that men preferred “an exclusive diet of thick mutton chops, brawny steaks, large ribs of beef and mountainous apple pies” while women went for “chicken patties, asparagus points and meringue shells.” But he declared this false, saying in his experience women “want their double sirloins as big as those served to their husbands,” while the most popular choice at a NY men’s club was “creamed chicken with sherry,” despite the fact that the chicken was cut up into small chunks.

But there may still have been some resistance on the part of men about eating foods tagged as feminine. Salads are one example, a favorite with women since the 19th century, but not so much with men. That included meat and fish salads, and in more modern times, green salads. And an industry publication reported in 1960 that a large hotel lured men into ordering a sandwich by naming it “The Mountain Climber.” It was made of turkey, ham, and cheese and had been previously ordered only by women.

However, as much as the differences in the restaurant orders of men and women may have declined in the late 20th century, it seems that with a few exceptions women still haven’t achieved equal stature or full recognition as gourmets or culinary pace-setters.

I’d love to hear readers’ thoughts on this topic.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.