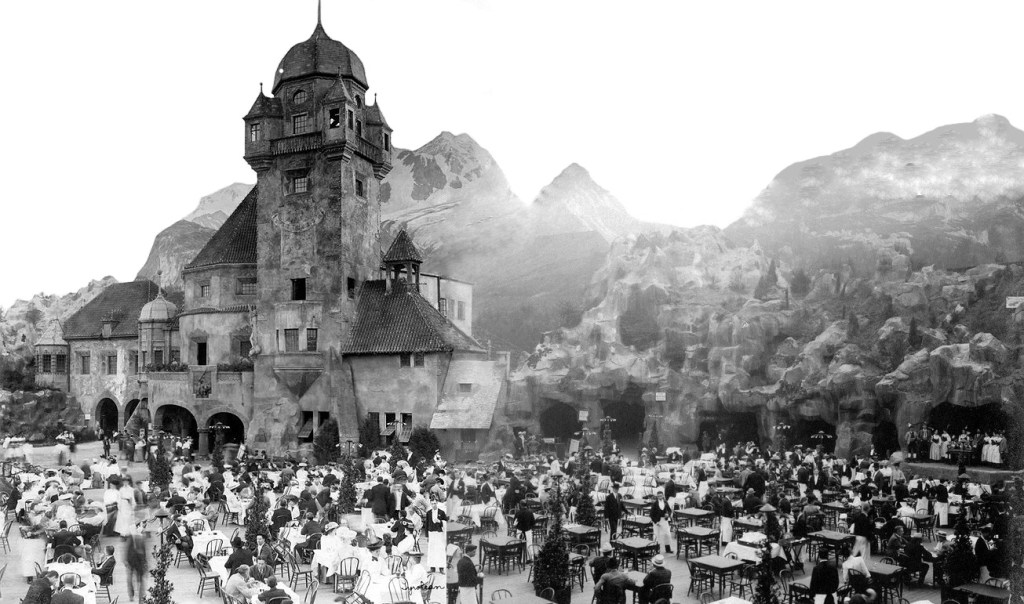

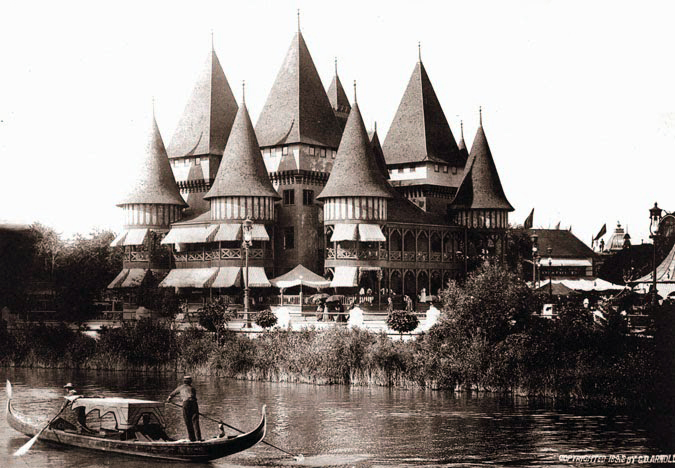

The 19th century was the century of world’s fairs, but the United States did not have a fair to call its own until 1876 when Philadelphia celebrated the 100th anniversary of U.S. independence. After Philadelphia, Chicago’s, in 1893, was the largest in this country. [above, outdoor beer garden at the Tyrolean Alps]

So . . . for St. Louis organizers of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904, when St. Louis was the fourth largest American city, second-largest Chicago figured as the one to beat. St. Louis fair organizers hoped to surpass the Chicago fair in all ways, particularly attendance.

The St. Louis fairgrounds occupied an immense 1,200 acres, double the area of Chicago’s. Not only was the area very large but so were the buildings. A hotel on the fairgrounds, the Inside Inn, had 2,357 rooms and dining rooms accommodating 2,500 at a time. The Palace of Agriculture building alone covered 23 acres. Big money too: the entire outlay for the city, U.S. government, participating nations and states, exhibitors, and concessionaires came to over $500M in today’s dollars.

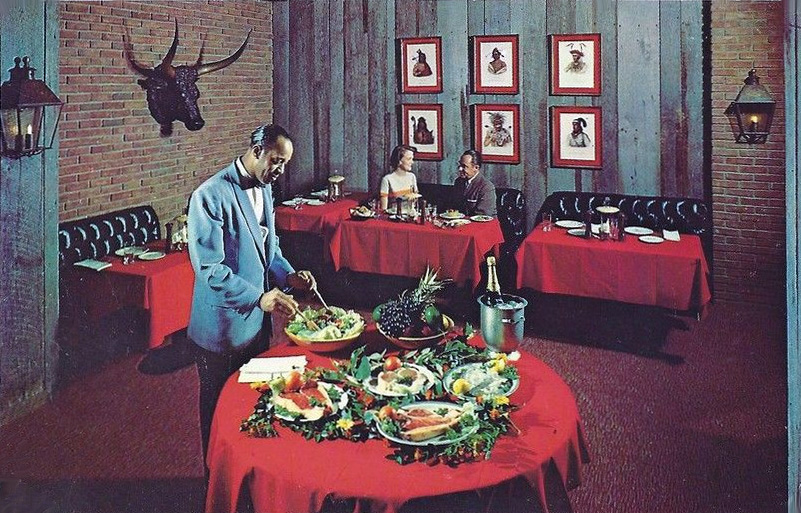

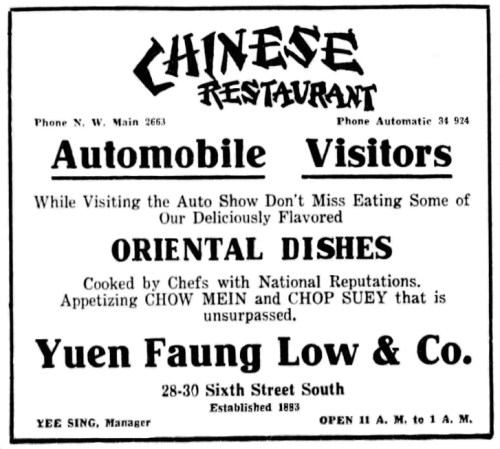

Planning the fair’s restaurants, with enough variety in fare and price to please fairgoers, was a formidable task. In St. Louis, those interested in being considered included owners of existing city restaurants, experienced professionals who made a career of running restaurants at fairs, various exhibitors who wanted to include a themed restaurant as an added attraction, some state and foreign nation buildings and exhibits, and food and drink companies and promoters.

The offerings ranged from about 50 stands selling sandwiches to 75 full-scale restaurants, some of them expensive. There were also oddities such as a proposed underground eating spot in the Anthracite Mining exhibit’s coal mine with waiters dressed as miners. Or, the restaurant in Hereafter — a tour through Dante’s Inferno — where diners ate off coffins in the Café of the Dead, probably an imitation of the Café of Death in Paris’ Montmartre.

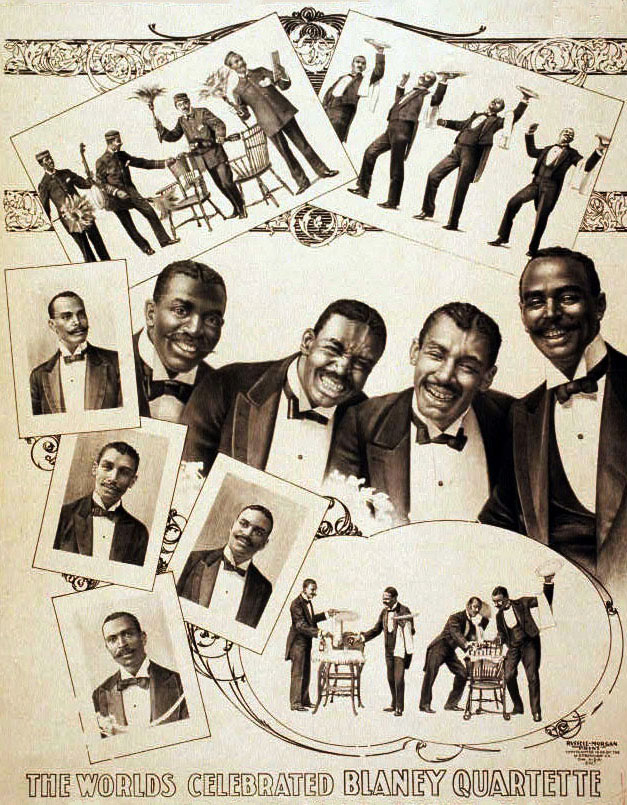

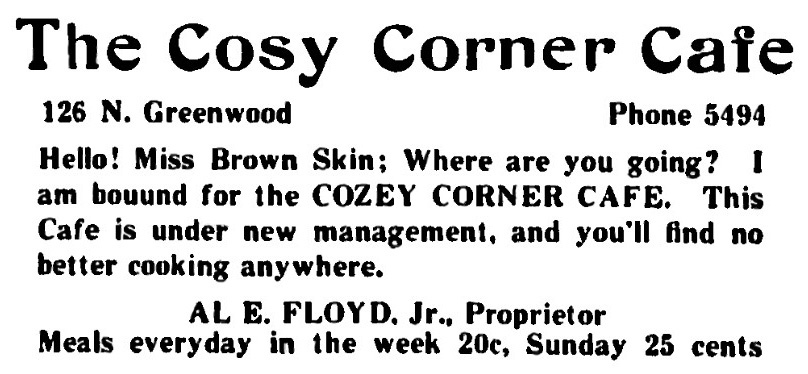

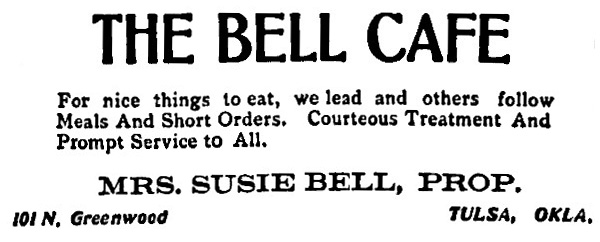

Without a doubt the most lavish, expensive, huge, and overall outstanding restaurant was the Tyrolean Alps, organized by two prominent restaurateurs, New York’s August Luchow and St. Louis’ Tony Faust, plus three other experienced St. Louis caterers, and with many backers including St. Louis brewer Adolphus Busch. Like several others it could handle an estimated 2,500 diners at a time. Despite all the banquets it catered, the famous people who dined there, its extensive menu, its general popularity, and its gross receipts of nearly $1M, like so many concessions it managed to lose money by fair’s end. It carried on for a time post-fair, into the summer of 1905.

Even before the fair ended some restaurant concessions had failed. The two owners of the Japanese restaurants [shown above], overcome with debt, filed for bankruptcy. The German Wine restaurant that charged $2 for a lunch with wine, proved to be far too expensive for fairgoers. Also, beer, not wine, was the preferred beverage at the fair, costing a nickel for a glass or a dime for a stein. Beer pavilions, such as Falstaff’s and Blatz’s, competed with the almighty Budweiser, widely available and practically the official beer of at least 17 of the restaurants.

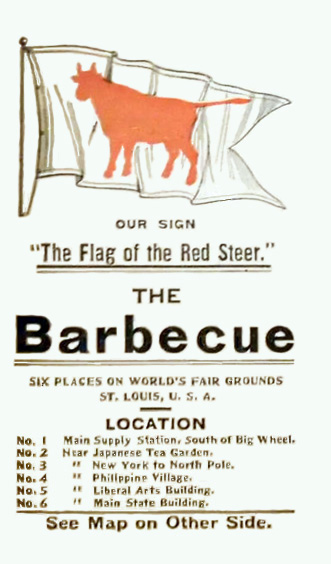

I haven’t found reports on how well the food stands did, but I’m guessing they fared better than many of the full-scale restaurants. The Barbecue, with six stands spread around the fairgrounds, was quite popular with the crowds. A reporter from Wichita KS let her readers know that it was a good deal, not requiring much money or time in being served, whether ordering hot beef, pork, mutton or sausage sandwiches. Plus, she reported, they supplied free paper cups and spoons (!).

Another winner was the enormous Inside Inn, the only hotel on the fairgrounds and the biggest financial success of the fair. A ham sandwich was 10 cents, while a complete dinner was 75 cents, and breakfast and lunch each cost 50 cents. At fair’s end, the Inn showed a sizable profit.

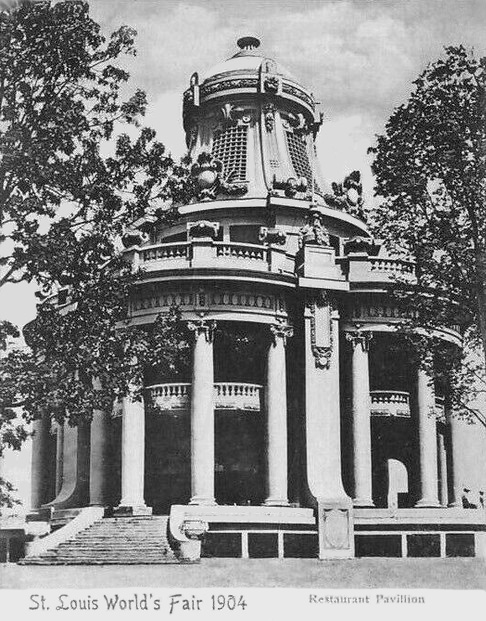

There were about a half dozen women operating restaurants. Prominent among them was well-known cookbook author Sarah Tyson Rorer who had also been at the Chicago fair. She ran a large restaurant seating 1,200 prominently located in the East Pavilion building [shown above], and she taught cooking classes. Harriet McMurphy, a food reformer and domestic science lecturer from Omaha, ran an eating place designed for people with digestive difficulties. She had very definite ideas of what was best to eat, rejecting pastry as something that should not be eaten more than once a year. Instead she offered baked apples with almonds and whipped cream. A local woman, Mrs. Reid, operated a breezy tea room called The Bungalow designed for women guests.

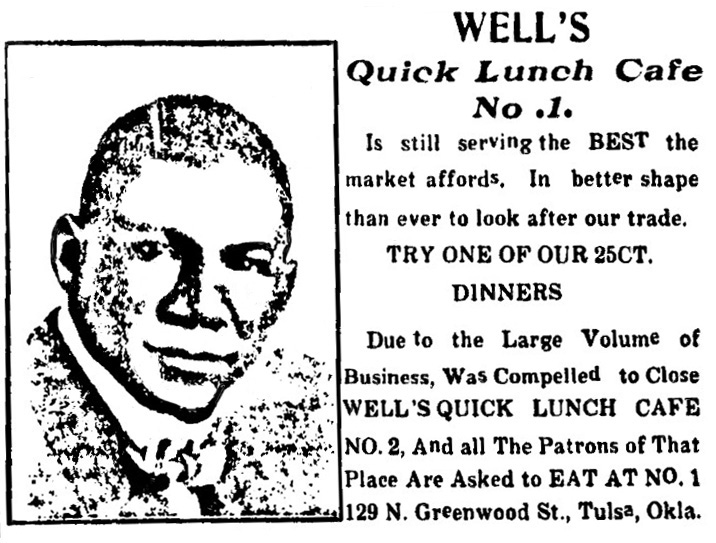

A few of the women restaurant operators also did the catering for some of the many banquets given during the fair, possibly including wedding ceremonies held in Ferris wheel gondolas [visible above] accommodating 60 persons.

The St. Louis fair has often been criticized for its disrespectful treatment of Philippine tribal people brought there to demonstrate the U.S.’s beneficial domination of developing nations considered inferior. Evidently they adjusted to modernity very quickly, soon tiring of the rice diet they were fed at the fair and demanding an American diet such as found at the restaurants. They were granted their wish.

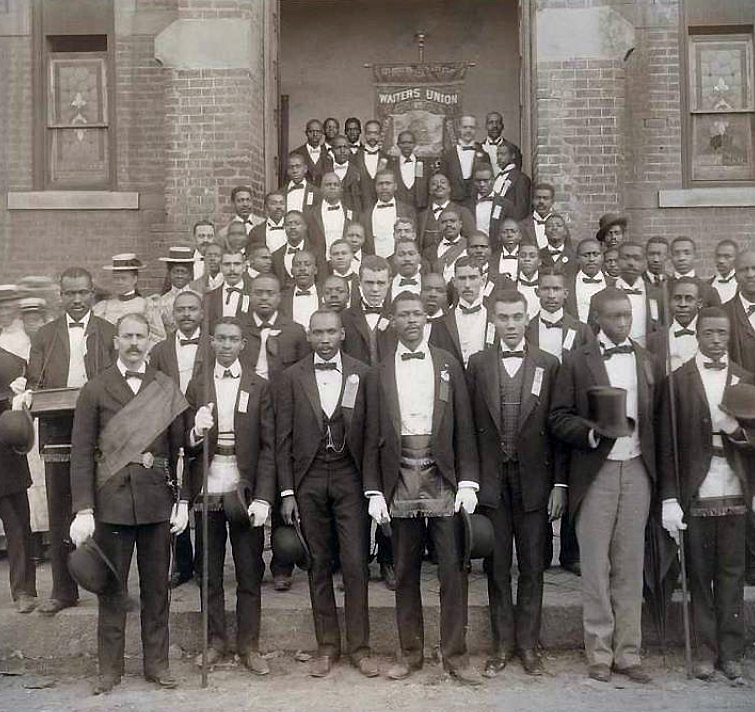

A lesser known scandal was how Black fairgoers were treated. In June, a group of Black visitors observed notices posted by restaurants on the Pike that read “No colored people served in this restaurant.” Then complaints were received that white servers were refusing to sell glasses of water to Black visitors, claiming that if they did they would lose their white customers. The fair organizers expressed dismay and there was discussion about hiring a Black woman who would run a stand to greet visitors of color, but that did not materialize and the number of Black visitors declined. The water issue was supposed to be “solved” with separate tanks of water and distinctively marked glasses. Unsurprisingly, the Black press denounced the fair. The Cleveland Gazette, for instance, advised “Our people had better stay away from the St. Louis World’s fair. There is much discrimination on the grounds.”

In the end, the St. Louis World’s Fair drew about 8 million fewer visitors than had Chicago’s exposition. The sideshow amusements lost so much money that the chairman of the Pike Financing Co. reported, “So universal has been the losing on the Pike that not one of the St. Louis shows will be taken to Portland,” the site of the next big fair. Despite all the losses for private investors who naively expected to make money, the fair’s Exposition Company managed to break even after paying back government loans.

© Jan Whitaker, 2024

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.