Staked by his brother-in-law, gambler Arnold Rothstein, Henry Lustig expanded from the wholesale produce business into restaurants in 1919. His first location, at 78th and Madison Avenue, was a property that belonged to Arnold. By 1924 he had two more restaurants, one conveniently near Saks Fifth Avenue. An advertisement informed “Madame or Mademoiselle” that at Longchamps they would find light French dishes as well as “soothing quiet, faultless service and a typically ‘Continental’ cuisine” that was above average “yet … not expensive.” While not exactly cheap, Longchamps was considered easily affordable by the middle-class.

Staked by his brother-in-law, gambler Arnold Rothstein, Henry Lustig expanded from the wholesale produce business into restaurants in 1919. His first location, at 78th and Madison Avenue, was a property that belonged to Arnold. By 1924 he had two more restaurants, one conveniently near Saks Fifth Avenue. An advertisement informed “Madame or Mademoiselle” that at Longchamps they would find light French dishes as well as “soothing quiet, faultless service and a typically ‘Continental’ cuisine” that was above average “yet … not expensive.” While not exactly cheap, Longchamps was considered easily affordable by the middle-class.

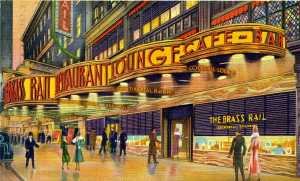

The chain continued to grow rapidly after the repeal of Prohibition when it hired top modernist decorators and architects to give it ultra-sophisticated chic. With the assistance of German-born artist and designer Winold Reiss and architects Louis Allen Abramson and Ely Jacques Kahn, New York City gained some of its most glamorous restaurant interiors of the period. Reiss showed considerable talent in disguising irregular spaces with mirrors and murals, multiple levels, dramatic lighting, and flashy staircases that lured people cheerfully downward to dine below ground (see his interior sketch and menu cover below). From 1935 to 1940 Longchamps opened seven new restaurants, including two on Broadway, one at Lexington and 42nd Street, and one in the Empire State Building.

Cocktail bars were no small part of the slick 1930s Longchamps formula. The chain’s ninth unit at Madison and 59th Street, a site vacated by Reuben’s, had a long oval bar stationed above floor level in the middle of the dining room. With 50 bartenders staffing the bar, the restaurant itself seated 950 diners. When it opened in 1935 a Longchamps advertisement immodestly called it “The Outstanding Restaurant Creation of the Century.” Architectural critic Lewis Mumford found its red, black, gold, and yellow color scheme — carried out even on chair backs and table tops — overdone, but he sensed that his was a minority opinion and he was almost certainly right. Among others, it soon became a meeting place for James Beard and his old friends from Oregon.

Cocktail bars were no small part of the slick 1930s Longchamps formula. The chain’s ninth unit at Madison and 59th Street, a site vacated by Reuben’s, had a long oval bar stationed above floor level in the middle of the dining room. With 50 bartenders staffing the bar, the restaurant itself seated 950 diners. When it opened in 1935 a Longchamps advertisement immodestly called it “The Outstanding Restaurant Creation of the Century.” Architectural critic Lewis Mumford found its red, black, gold, and yellow color scheme — carried out even on chair backs and table tops — overdone, but he sensed that his was a minority opinion and he was almost certainly right. Among others, it soon became a meeting place for James Beard and his old friends from Oregon.

During the war Longchamps’ did a booming business. Lustig, it turned out, was siphoning off cash as fast as he could and keeping two sets of books, one for him and one for the IRS. Keep in mind that he owned racehorses and had named his restaurants after a famous Paris racetrack. The game was up in 1946 when he was handed a bill for delinquent taxes and fines of more than $10M and sentenced to four years in federal prison. Nine restaurants, along with a good stock of wine (the Times Square unit alone was said to have 120,000 bottles in the cellar), miscellaneous pieces of Manhattan real estate, and the chain’s bakery, catering business, ice cream plant, candy factory, and commissary, then passed into the hands of a syndicate which owned the Exchange Buffet.

During the war Longchamps’ did a booming business. Lustig, it turned out, was siphoning off cash as fast as he could and keeping two sets of books, one for him and one for the IRS. Keep in mind that he owned racehorses and had named his restaurants after a famous Paris racetrack. The game was up in 1946 when he was handed a bill for delinquent taxes and fines of more than $10M and sentenced to four years in federal prison. Nine restaurants, along with a good stock of wine (the Times Square unit alone was said to have 120,000 bottles in the cellar), miscellaneous pieces of Manhattan real estate, and the chain’s bakery, catering business, ice cream plant, candy factory, and commissary, then passed into the hands of a syndicate which owned the Exchange Buffet.

In 1952 a Longchamps was opened in Washington, D.C., becoming one of the few downtown restaurants in that city that served Afro-American patrons. About this time another Longchamps opened in the Claridge apartments on Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square. In 1959 the chain was acquired by Jan Mitchell, owner since 1950 of the old Lüchow’s. He revealed that the chain, which consisted of twelve red and gold restaurants, a poorly trained kitchen staff, and a diminishing patronage, had been losing money for the past five years but that he could revive it as he had done with Lüchow’s. Under his ownership the New York units began offering guests the dietary concoction Metracal in their cocktail lounges, as well as free glasses of wine and corn on the cob with their meal. After a couple of years the chain was in the black.

In 1952 a Longchamps was opened in Washington, D.C., becoming one of the few downtown restaurants in that city that served Afro-American patrons. About this time another Longchamps opened in the Claridge apartments on Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square. In 1959 the chain was acquired by Jan Mitchell, owner since 1950 of the old Lüchow’s. He revealed that the chain, which consisted of twelve red and gold restaurants, a poorly trained kitchen staff, and a diminishing patronage, had been losing money for the past five years but that he could revive it as he had done with Lüchow’s. Under his ownership the New York units began offering guests the dietary concoction Metracal in their cocktail lounges, as well as free glasses of wine and corn on the cob with their meal. After a couple of years the chain was in the black.

In 1967 Mitchell sold it to the Riese brothers, who owned the Childs restaurants and, with new corporation president Larry Ellman, were in the process of buying up classic New York restaurants – Cavanagh’s in 1968, Lüchow’s in 1969, and others. In 1969 the old Longchamps were mostly turned into steakhouse theme restaurants. The restaurant at Madison and 59th, though, was renamed the Orangerie, dedicated to “hedonistic New Yorkers,” and given a “festive mood of Monte Carlo.” Its $8.75 prix fixe dinner came with free wine, “Unique La ‘Tall’ Salade,” and after-dinner coffee with Grand Marnier. In 1971 a single Longchamps operated under that name, at Third Avenue and 65th Street, but I doubt it had anything in common with the classic Longchamps of the 1930s. The holding company “Longchamps, Inc.” vanished in 1975.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

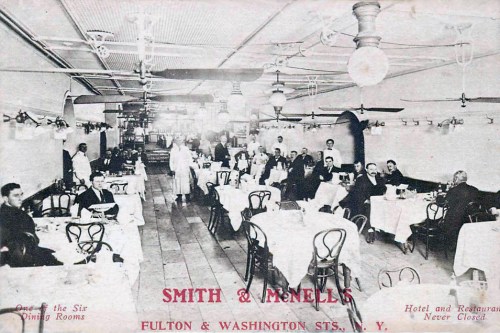

All things considered, the best restaurants that this country has produced probably have been unpretentious, inexpensive, high-volume eateries located close to sources of fresh food. In 19th-century New York City’s Smith & McNell’s, across from the booming Washington Market, was a leading example of the type. Its patronage came largely from dealers, farmers, and customers who worked and shopped at the market. Around 1891 the restaurant reportedly provided more meals than any eating place in the city, as many as 10,000 a day.

All things considered, the best restaurants that this country has produced probably have been unpretentious, inexpensive, high-volume eateries located close to sources of fresh food. In 19th-century New York City’s Smith & McNell’s, across from the booming Washington Market, was a leading example of the type. Its patronage came largely from dealers, farmers, and customers who worked and shopped at the market. Around 1891 the restaurant reportedly provided more meals than any eating place in the city, as many as 10,000 a day. There are many discrepancies in accounts of this restaurant’s history but it seems most likely it was established in the late 1840s by Thomas R. McNell and Henry Smith. McNell was an Irish immigrant, born sometime between 1825 and 1830. According to one account he and Smith had been night watchmen before taking over the coffee house run by Frederick Way on Washington Street near the market. Both McNell and Smith became wealthy and McNell acquired a lordly estate in Alpine, New Jersey, as well as a California ranch. He continued working in the business until a ripe old age and died in 1917 a few years after the restaurant (and associated hotel) closed.

There are many discrepancies in accounts of this restaurant’s history but it seems most likely it was established in the late 1840s by Thomas R. McNell and Henry Smith. McNell was an Irish immigrant, born sometime between 1825 and 1830. According to one account he and Smith had been night watchmen before taking over the coffee house run by Frederick Way on Washington Street near the market. Both McNell and Smith became wealthy and McNell acquired a lordly estate in Alpine, New Jersey, as well as a California ranch. He continued working in the business until a ripe old age and died in 1917 a few years after the restaurant (and associated hotel) closed.

In the late 19th century owners of large popular-price restaurants began to look for ways to cut costs and eliminate waiters. The times were hospitable to mechanical solutions and in 1902 automatic restaurants opened in Philadelphia (pictured below) and New York. In both cities, a clever coin-operated set-up – and a name – were imported from

In the late 19th century owners of large popular-price restaurants began to look for ways to cut costs and eliminate waiters. The times were hospitable to mechanical solutions and in 1902 automatic restaurants opened in Philadelphia (pictured below) and New York. In both cities, a clever coin-operated set-up – and a name – were imported from  The Automat in NYC was owned by James Harcombe, who in the 1890s had acquired Sutherland’s, one of the city’s old landmark restaurants located on Liberty Street. The Harcombe Restaurant Company’s Automat was at 830 Broadway, near Union Square. Reportedly costing more than $75,000 to install, it was a marvel of invention decorated with inlaid mirror, richly colored woods, and German proverbs. It served forth sandwiches and soups, dishes such as fish chowder and

The Automat in NYC was owned by James Harcombe, who in the 1890s had acquired Sutherland’s, one of the city’s old landmark restaurants located on Liberty Street. The Harcombe Restaurant Company’s Automat was at 830 Broadway, near Union Square. Reportedly costing more than $75,000 to install, it was a marvel of invention decorated with inlaid mirror, richly colored woods, and German proverbs. It served forth sandwiches and soups, dishes such as fish chowder and  Undeterred by the first Automat’s fate, Horn & Hardart moved into New York in 1912, opening an Automat of their own manufacture at Broadway and 46th Street (pictured). It turned out that New Yorkers did indeed use slugs, especially in 1935 when 219,000 were inserted into H&H slots. But despite this, the automatic restaurant prospered, expanded, and became a New York institution. By 1918 there were nearly 50 Automats in the two major cities, and eventually a few in Boston. Horn & Hardart tried Automats in Chicago in the 1920s but they were a failure. On an inspection tour in Chicago, Joseph Horn noted problems such as weak coffee, “figs not right,” and “lem. meringue very bad.”

Undeterred by the first Automat’s fate, Horn & Hardart moved into New York in 1912, opening an Automat of their own manufacture at Broadway and 46th Street (pictured). It turned out that New Yorkers did indeed use slugs, especially in 1935 when 219,000 were inserted into H&H slots. But despite this, the automatic restaurant prospered, expanded, and became a New York institution. By 1918 there were nearly 50 Automats in the two major cities, and eventually a few in Boston. Horn & Hardart tried Automats in Chicago in the 1920s but they were a failure. On an inspection tour in Chicago, Joseph Horn noted problems such as weak coffee, “figs not right,” and “lem. meringue very bad.” The Automats hit their peak in the mid-20th century. Slugs aside, the Depression years were better for business than the wealthier 1960s and 1970s when some units were converted to Burger Kings. In 1933 H&H hired Francis Bourdon, the French chef at the Sherry Netherland (fellow chefs called him “L’Escoffier des Automats”). In 1969 Philadelphia’s first Automat closed, being declared “a museum piece, inefficient and slow, in a computerized world.” That left two in Philadelphia and eight in NYC. The last New York Automat, at East 42nd and 3rd Ave, closed in 1991.

The Automats hit their peak in the mid-20th century. Slugs aside, the Depression years were better for business than the wealthier 1960s and 1970s when some units were converted to Burger Kings. In 1933 H&H hired Francis Bourdon, the French chef at the Sherry Netherland (fellow chefs called him “L’Escoffier des Automats”). In 1969 Philadelphia’s first Automat closed, being declared “a museum piece, inefficient and slow, in a computerized world.” That left two in Philadelphia and eight in NYC. The last New York Automat, at East 42nd and 3rd Ave, closed in 1991. James Beard enjoyed eating out – in fact much of his life revolved around restaurants. When he was a child his mother often took him to places such as the Royal Bakery in his hometown of Portland OR and Tait’s in San Francisco (pictured). Although he was an accomplished cook, cooking teacher, and author of over 20 cookbooks, like many a New Yorker he patronized restaurants frequently, including

James Beard enjoyed eating out – in fact much of his life revolved around restaurants. When he was a child his mother often took him to places such as the Royal Bakery in his hometown of Portland OR and Tait’s in San Francisco (pictured). Although he was an accomplished cook, cooking teacher, and author of over 20 cookbooks, like many a New Yorker he patronized restaurants frequently, including  He preferred restaurants that were “homey” and where he was known and liked, such as the Coach House and Quo Vadis. At the latter he became good friends with owners Bruno Caravaggi and Gino Robusti with whom he shared a love of opera. As a young man (pictured, age 19) he prepared for a musical career at London’s Royal Academy of Music. He said that his early performance training helped him with radio and TV appearances.

He preferred restaurants that were “homey” and where he was known and liked, such as the Coach House and Quo Vadis. At the latter he became good friends with owners Bruno Caravaggi and Gino Robusti with whom he shared a love of opera. As a young man (pictured, age 19) he prepared for a musical career at London’s Royal Academy of Music. He said that his early performance training helped him with radio and TV appearances.

The Downing family of caterers and restaurateurs, Thomas and his sons George T. and Peter W., were activists in the causes of the abolition of slavery, black suffrage, and black education. They assisted Afro-Americans fleeing slavery before Emancipation as well as those escaping terrorism in the South in the post-Civil War period. Like many free blacks living in cities, they took up the catering trade. Similar to undertaking and barbering, catering was a personal service occupation which offered a degree of opportunity for enterprising people of color.

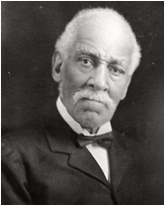

The Downing family of caterers and restaurateurs, Thomas and his sons George T. and Peter W., were activists in the causes of the abolition of slavery, black suffrage, and black education. They assisted Afro-Americans fleeing slavery before Emancipation as well as those escaping terrorism in the South in the post-Civil War period. Like many free blacks living in cities, they took up the catering trade. Similar to undertaking and barbering, catering was a personal service occupation which offered a degree of opportunity for enterprising people of color. Thomas Downing (pictured), the son of freed slaves from Virginia, specialized in oysters. He opened an oyster cellar on Broad Street in New York City in the 1820s, gradually expanding it and earning a fine reputation. Often oyster cellars were “dives” but his was considered first class. He won awards for his pickled oysters which, along with his boned and jellied turkeys, were especially popular at Christmas (see 1856 ad). Over time he owned the Broad Street place and at least one other in NYC and, according to a Rhode Island directory, another in Providence. However, the press seemed always to confuse the various Downings, so it’s possible the latter was under the direction of a son.

Thomas Downing (pictured), the son of freed slaves from Virginia, specialized in oysters. He opened an oyster cellar on Broad Street in New York City in the 1820s, gradually expanding it and earning a fine reputation. Often oyster cellars were “dives” but his was considered first class. He won awards for his pickled oysters which, along with his boned and jellied turkeys, were especially popular at Christmas (see 1856 ad). Over time he owned the Broad Street place and at least one other in NYC and, according to a Rhode Island directory, another in Providence. However, the press seemed always to confuse the various Downings, so it’s possible the latter was under the direction of a son. Thomas’s place on Broad was patronized by men in political and financial circles and he was rumored to have influential connections. Both his sons, George and Peter, had enough pull to win concessions for restaurants in government buildings. Peter ran an eating place in the Customs House in NYC, while George, a friend of MA Senator Charles Sumner, managed one in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. George (pictured) was also well known as the proprietor of a resort hotel, the Sea Girt House, in Newport, Rhode Island.

Thomas’s place on Broad was patronized by men in political and financial circles and he was rumored to have influential connections. Both his sons, George and Peter, had enough pull to win concessions for restaurants in government buildings. Peter ran an eating place in the Customs House in NYC, while George, a friend of MA Senator Charles Sumner, managed one in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. George (pictured) was also well known as the proprietor of a resort hotel, the Sea Girt House, in Newport, Rhode Island. Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms.

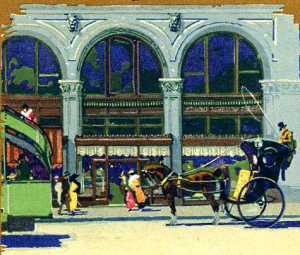

Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms. Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests.

Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests. Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.”

Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.”

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.