Edmund Hill began working in his father’s bakery and restaurant full-time in 1873 when he was 18. His help was needed because of his father’s poor health. He wanted to go on to Yale, yet he devoted his career to the business, which was operated under his father’s name Thomas C. Hill.

Edmund Hill began working in his father’s bakery and restaurant full-time in 1873 when he was 18. His help was needed because of his father’s poor health. He wanted to go on to Yale, yet he devoted his career to the business, which was operated under his father’s name Thomas C. Hill.

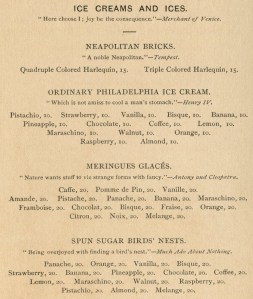

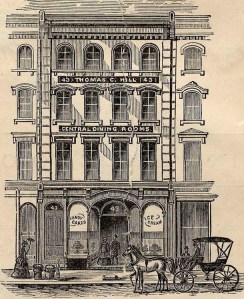

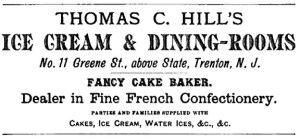

Thomas Hill founded the business in 1860, rapidly becoming one of the city’s leading caterers and furnishing everything needed for soirees, suppers, and weddings except, as a 1866 newspaper story remarked, the brides and bridegrooms. Located in the center of Trenton, New Jersey, the restaurant advertised in 1882 that it was “the largest and finest between New York and Philadelphia” and could provide in its dining rooms or beyond all the fancy dishes of the day: boned turkeys, croquettes, rissoles, jellied meats, carved ice blocks, charlottes, spun sugar centerpieces, and bon bons. Hill’s hosted many organizations at its Greene Street location, including the Young Men’s Gymnastic Association whose members stuffed themselves in 1883 with many of the above plus a variety of ice creams, meringues, and walnut kisses. He specialized in fancy desserts, as is demonstrated by a portion of an 1883 souvenir menu shown here (courtesy of Henry Voigt — The American Menu).

Thomas Hill founded the business in 1860, rapidly becoming one of the city’s leading caterers and furnishing everything needed for soirees, suppers, and weddings except, as a 1866 newspaper story remarked, the brides and bridegrooms. Located in the center of Trenton, New Jersey, the restaurant advertised in 1882 that it was “the largest and finest between New York and Philadelphia” and could provide in its dining rooms or beyond all the fancy dishes of the day: boned turkeys, croquettes, rissoles, jellied meats, carved ice blocks, charlottes, spun sugar centerpieces, and bon bons. Hill’s hosted many organizations at its Greene Street location, including the Young Men’s Gymnastic Association whose members stuffed themselves in 1883 with many of the above plus a variety of ice creams, meringues, and walnut kisses. He specialized in fancy desserts, as is demonstrated by a portion of an 1883 souvenir menu shown here (courtesy of Henry Voigt — The American Menu).

Edmund’s diary from 1876 through 1885 has been transcribed and digitized by the Trenton Historical Society and makes fascinating reading. Among other things it gives rare glimpses into the running of a combined bakery, restaurant, confectionery, and catering business in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. Edmund was a reluctant restaurateur. As the Historical Society’s site says, “Edmund severely disliked, even hated, working in the restaurant business and he focused much of his energies elsewhere, such as pursuing real estate and civic affair concerns throughout Trenton.”

Edmund’s diary from 1876 through 1885 has been transcribed and digitized by the Trenton Historical Society and makes fascinating reading. Among other things it gives rare glimpses into the running of a combined bakery, restaurant, confectionery, and catering business in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. Edmund was a reluctant restaurateur. As the Historical Society’s site says, “Edmund severely disliked, even hated, working in the restaurant business and he focused much of his energies elsewhere, such as pursuing real estate and civic affair concerns throughout Trenton.”

Despite Edmund’s lifelong disappointment over being forced to take up a trade, he ran a successful business which he diligently kept abreast with the progress of the times, remodeling the restaurant, increasing baking capacity, and installing electricity. In the 1880s Hill’s restaurant and catering service, almost certainly run on a temperance basis, was known throughout New Jersey. And it made money as his diary entry of December 31, 1881, shows: “Finished up accounts in store. We took in $18,146.60, against $15,294.40 last year. Very satisfactory all around.”

Edmund became an expert cake baker and could, and did, fill in for just about any employee. In 1880 he paid his German baker to teach him how to make the Vienna bread made popular by the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. (“Bargained with Karl to teach me baking for twenty five dollars.”) On at least two occasions he organized a series of public cooking lessons taught in Trenton by cookbook author Maria Parloa of New York. In his diary he wrote that he found her lecture on bass with tartar sauce, baked fish with hollandaise sauce, ginger bread and vegetables “very instructive.”

When he traveled to New York City or other cities he often ate at leading restaurants and probably toured their facilities. He mentions going to Dorlon’s, the renowned oyster restaurant in Fulton Market as well as Delmonico’s, the Hotel Bellevue, the Astor House, and the Vienna Model Bakery, all in NYC. He went to Moretti’s – Charles Delmonico’s favorite place for ravioli – but evidently did not care for it. (“Do not like Italian cooking.”) He even attended the French Cooks Ball to check out the fare. (“Dresses and dancing were ridiculous. The tables were superb.”)

When he traveled to New York City or other cities he often ate at leading restaurants and probably toured their facilities. He mentions going to Dorlon’s, the renowned oyster restaurant in Fulton Market as well as Delmonico’s, the Hotel Bellevue, the Astor House, and the Vienna Model Bakery, all in NYC. He went to Moretti’s – Charles Delmonico’s favorite place for ravioli – but evidently did not care for it. (“Do not like Italian cooking.”) He even attended the French Cooks Ball to check out the fare. (“Dresses and dancing were ridiculous. The tables were superb.”)

In addition to ensuring the reputation of Hill’s Restaurant and Bakery, he was a well-off, well-read man of the world who traveled to Europe several times, a successful real estate developer, a banker, a city councilman, an esteemed civic benefactor, as well as a devoutly religious family man. He was friends with famous people, including Leo Tolstoy, whose son he hosted at an honorary dinner at Delmonico’s. Yet, according to the Historical Society’s site, he never got over having to end his education to take over the family business and considered himself a failure.

He sold the restaurant building and all his catering equipment in 1905 while moving the bakery which continued in business for many years thereafter.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.