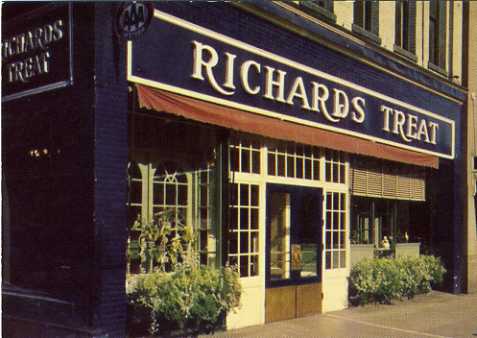

With its ham loaf and chicken pot pie, the Richards Treat Cafeteria on South Sixth Street in downtown Minneapolis was akin to other cafeterias and restaurants run by women, such as The Maramor in Columbus, Miss Hulling’s in St. Louis, and the Anna-Maude in Oklahoma City. Like its sisters, the Richards Treat was not known for culinary innovation but for preparing home-like dishes from scratch using fresh ingredients cooked in small batches.

With its ham loaf and chicken pot pie, the Richards Treat Cafeteria on South Sixth Street in downtown Minneapolis was akin to other cafeterias and restaurants run by women, such as The Maramor in Columbus, Miss Hulling’s in St. Louis, and the Anna-Maude in Oklahoma City. Like its sisters, the Richards Treat was not known for culinary innovation but for preparing home-like dishes from scratch using fresh ingredients cooked in small batches.

The Richards Treat was opened in 1924 by two home economics professors at the University of Minnesota, Lenore Richards and Nola Treat, who ran the successful enterprise until 1957. The two met in 1915 when they both taught at Kansas State Agricultural College in Manhattan KS. They became close and decided to arrange their lives so they could work and live together from then on. “I am not and never have been married,” each wrote in 1923 when applying for passports prior to a European tour.

Nola Treat [pictured, 1923] had some experience in running cafeterias before 1924. She had set up a high school cafeteria in Decatur IL in 1911 when many schools provided no meal service. Following that she inaugurated student cafeterias and institutional management programs at several Midwestern state colleges and universities. Apparently she was well aware that many people disliked cafeterias, publishing an article titled “Why Cafeterias Fail” just months before opening her own. In it she said that it was unusual to find the sort of cafeteria which was “so attractive in appearance, and which serves such good food, that the most fastidious people will go to it.”

Nola Treat [pictured, 1923] had some experience in running cafeterias before 1924. She had set up a high school cafeteria in Decatur IL in 1911 when many schools provided no meal service. Following that she inaugurated student cafeterias and institutional management programs at several Midwestern state colleges and universities. Apparently she was well aware that many people disliked cafeterias, publishing an article titled “Why Cafeterias Fail” just months before opening her own. In it she said that it was unusual to find the sort of cafeteria which was “so attractive in appearance, and which serves such good food, that the most fastidious people will go to it.”

Perhaps that was why Richards and Treat always paid such close attention to their restaurant’s decor, which had little in common with the typical cafeteria’s institutional appearance. Theirs more nearly resembled a tea room with its antique cupboard of curly maple, pewter objects from the couple’s collection, and other decorative pieces brought back from their travels. Each table in the main dining room, including the one where they ate their own dinner nightly, held glowing candles in candlestick holders or candelabra.

Perhaps that was why Richards and Treat always paid such close attention to their restaurant’s decor, which had little in common with the typical cafeteria’s institutional appearance. Theirs more nearly resembled a tea room with its antique cupboard of curly maple, pewter objects from the couple’s collection, and other decorative pieces brought back from their travels. Each table in the main dining room, including the one where they ate their own dinner nightly, held glowing candles in candlestick holders or candelabra.

In their cafeteria they attempted to provide a home substitute for patrons who might be unable to get home for meals or who lived in efficiency apartments. “The atmosphere of the dining room – its quiet, order, cleanliness – contribute to a feeling of well-being and satisfaction in the food,” observed Lenore [pictured, 1923] in a 1941 address to the Home Economics Association.

In their cafeteria they attempted to provide a home substitute for patrons who might be unable to get home for meals or who lived in efficiency apartments. “The atmosphere of the dining room – its quiet, order, cleanliness – contribute to a feeling of well-being and satisfaction in the food,” observed Lenore [pictured, 1923] in a 1941 address to the Home Economics Association.

Their menus featured American cooking as understood by the middle-class American-born mainstream in the mid-20th century. An April 1933 menu offered a special 50-cent dinner of Veal Loaf with Mushroom Sauce, Buttered New Asparagus and Carrots, and desserts such as Fresh Strawberry Shortcake or Devils Food Cake, accompanied by Coffee, Milk, or Buttermilk.

For 15 or more years the cafeteria supplied cakes for dining cars of the Great Northern Railroad. When they learned, quite by accident, that the cakes’ top layers had a habit of sliding off when trains went over mountains en route to Seattle, they substituted sheet cakes. Cakes, cookies, bread, and house-made candy were popular sellers at the cafeteria’s bake counter where, in the 1940s, they also sold Laguna Pottery from California.

The cafeteria became a place where lawyers, judges, professional men and women, and newspaper reporters gathered, leading restaurant guidebook publisher Duncan Hines to characterize it as “Educated Food for Educated People.” The slogan was adopted by the Richards Treat.

They expanded several times, seating 300 by 1944, and winning loyal patrons despite stiff competition from other cafeterias such as The Forum and Miller’s Cafeteria. They also ran a coffee shop in the Northwestern Bank Building. Throughout their career they received many accolades, served on the editorial board of Restaurant Management magazine, and held top positions in the National Restaurant Association. Their book Quantity Cooking, published in 1922, with three subsequent editions, became a basic text used by the US military in World War II and restaurants throughout the country into at least the 1970s.

© Jan Whitaker, 2012

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.