TURNING THE TABLES: RESTAURANTS AND THE RISE OF THE AMERICAN MIDDLE CLASS, 1880-1920, by Andrew P. Haley, University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

In the time that has elapsed since my reading this fine book — and getting to meet Andrew in person — and now, he has gathered numerous glowing reviews plus a 2012 James Beard Award. Proving he didn’t need any help from me to get the attention he deserved for this well-researched and highly readable book. Still, I’d like to see him get even more.

In the time that has elapsed since my reading this fine book — and getting to meet Andrew in person — and now, he has gathered numerous glowing reviews plus a 2012 James Beard Award. Proving he didn’t need any help from me to get the attention he deserved for this well-researched and highly readable book. Still, I’d like to see him get even more.

Turning the Tables is an investigation of the role of the American middle class in the creation of restaurants that suited their tastes, values, and habits: in other words, in creating the kinds of restaurants we patronize today, where the menu is streamlined and written in plain English, where women and children are welcome, and where food of many ethnicities is enjoyed. The book investigates in detail what it was about elite restaurants of the late Victorian age that average Americans disliked. And I must say it is refreshing to read an account of the making of our culture that portrays average people “turning the tables” and spreading access to the good things of life rather than aspiring to become privileged exclusivists.

HISTORIC RESTAURANTS OF WASHINGTON D.C., by John DeFerrari, The History Press/American Palate, 2013.

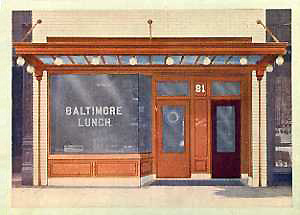

John is a preservationist and an authority on Washington. He is the author of Lost Washington and of the well-illustrated blog Streets of Washington. His book on the city’s restaurants is carefully researched and beautifully illustrated with postcards from his collection and photographs from the Library of Congress. There are eight pages of color illustrations, the remainder in black and white. Reading the book makes clear that even if Washington’s restaurants – like those of many cities across the nation – were long considered of little culinary interest, that doesn’t mean that their histories are any less significant. John has ferreted out plenty of evidence of the important role they played in the life of the city.

John is a preservationist and an authority on Washington. He is the author of Lost Washington and of the well-illustrated blog Streets of Washington. His book on the city’s restaurants is carefully researched and beautifully illustrated with postcards from his collection and photographs from the Library of Congress. There are eight pages of color illustrations, the remainder in black and white. Reading the book makes clear that even if Washington’s restaurants – like those of many cities across the nation – were long considered of little culinary interest, that doesn’t mean that their histories are any less significant. John has ferreted out plenty of evidence of the important role they played in the life of the city.

I particularly liked his chapters “Black Washington’s Restaurants” and “Power Lunches and Dinners.” And, of course, I appreciated that he included a chapter on tea rooms. I know I will be dipping back into his book many times as I write my own posts.

REPAST: DINING OUT AT THE DAWN OF A NEW AMERICAN CENTURY, 1900-1910, by Michael Lesy and Lisa Stoffer, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013

Michael Lesy is of course the author of the newly reissued, haunting classic Wisconsin Death Trip, as well as numerous other books. In Repast he has teamed up with his wife Lisa Stoller to write about turn-of-the-century dining, high and low, American, French, and other ethnicities. Splitting the task between them almost 50-50, Michael authored the Introduction and the chapters Pure Food, Quick Food, and Other People’s Food while Lisa wrote Her Food, Splendid Food, and the Afterword. Together the chapters create a vivid portrait of how people lived as reflected through their eating habits.

Michael Lesy is of course the author of the newly reissued, haunting classic Wisconsin Death Trip, as well as numerous other books. In Repast he has teamed up with his wife Lisa Stoller to write about turn-of-the-century dining, high and low, American, French, and other ethnicities. Splitting the task between them almost 50-50, Michael authored the Introduction and the chapters Pure Food, Quick Food, and Other People’s Food while Lisa wrote Her Food, Splendid Food, and the Afterword. Together the chapters create a vivid portrait of how people lived as reflected through their eating habits.

The book makes great use of the New York Public Library’s Buttolph menu collection which is particularly strong in the first decade of the 20th century. Many of the photographs shown in the book are from the incomparable Byron Company collection at the Museum of the City of New York. As a consequence, the book tends to favor New York particularly in the illustrations, which are printed beautifully in this handsome, full-color book.

Note cards by Cool Culinaria

The sprightly image of a menu from McDonnell’s Drive-In shown here, in 1940s Los Angeles, is from CC’s mixed set of ten cards, the American Collection. Other note card sets in their lineup include those of the Old West and the cities of Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, and San Francisco. I like how the inside left side of each card gives a glimpse of the menu’s interior.

The sprightly image of a menu from McDonnell’s Drive-In shown here, in 1940s Los Angeles, is from CC’s mixed set of ten cards, the American Collection. Other note card sets in their lineup include those of the Old West and the cities of Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York, and San Francisco. I like how the inside left side of each card gives a glimpse of the menu’s interior.

And, in case you were wondering what that brown bottle is that the female carhop carries on the tray, it is indeed beer. In addition to colas, ice cream sodas, and “churned buttermilk,” McDonnell’s served bottled beer and beer by the glass (10 cents), with a higher charge for Eastern beers than those brewed in the West! So let’s drink a toast to California’s unique concept of the drive-in and to Cool Culinaria’s mission of “Rescuing Vintage Menu Art from Obscurity.”

I published a recipe for The Aware Inn’s famed sandwich “The Swinger” some time back. But now I have a new improved version, thanks to Isis Aquarian, one of the members of Jim Baker’s commune when he was a spiritual leader named Father Yod. She was one of his 14 wives, as well as the commune’s historian and archivist. (A 2012 documentary film and book about the Source family commune is available.)

I published a recipe for The Aware Inn’s famed sandwich “The Swinger” some time back. But now I have a new improved version, thanks to Isis Aquarian, one of the members of Jim Baker’s commune when he was a spiritual leader named Father Yod. She was one of his 14 wives, as well as the commune’s historian and archivist. (A 2012 documentary film and book about the Source family commune is available.) According to Isis, Jack LaLanne was not much of a restaurant goer until Jim Baker and his wife opened up The Aware Inn. He became a frequent visitor, along with many other health-conscious Hollywood celebrities such as Ed “Kookie” Byrnes of the TV show Seventy-Seven Sunset Strip.

According to Isis, Jack LaLanne was not much of a restaurant goer until Jim Baker and his wife opened up The Aware Inn. He became a frequent visitor, along with many other health-conscious Hollywood celebrities such as Ed “Kookie” Byrnes of the TV show Seventy-Seven Sunset Strip.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.