Ever wonder why restaurants make such a big to-do with pepper mills? Obviously many people like freshly ground pepper but it goes beyond that. It’s a grand gesture that suggests hospitality and attention to detail. Diners may reason that if a restaurant will bother with fresh ground pepper it must bring the same degree of attention to its cooking.

Ever wonder why restaurants make such a big to-do with pepper mills? Obviously many people like freshly ground pepper but it goes beyond that. It’s a grand gesture that suggests hospitality and attention to detail. Diners may reason that if a restaurant will bother with fresh ground pepper it must bring the same degree of attention to its cooking.

Throughout the 19th century, Americans were lukewarm to the idea of grinding their own pepper. The custom was mainly followed in restaurants run by German or Italian proprietors. Around 1900 some people questioned whether modern Americans wanted to grind peppercorns. So Old World! A story in the New York Sun in 1903 reflected this attitude: “Beginning with the little boxes on the table where you can grind your own pepper while you wait – imagine having time to grind your own pepper – everything in the Teutonic eating places is a protest against the American idea of life.”

So pepper mills were un-American, at least for a while. But then, in the 1950s and early 1960s, competitive restaurateurs returned to the practice. For some reason – world travel? the rebirth of gourmet dining? – some guests had begun to carry around their own portable grinders. Restaurants may have felt a need to respond if they were to appear sophisticated. And so, along with Beef Wellington and large padded menus, the pepper grinder made its appearance. If it seemed European now, so much the better. Evidently pepper mills were quite the thing in Los Angeles around 1955 because there were at least two manufacturers there.

So pepper mills were un-American, at least for a while. But then, in the 1950s and early 1960s, competitive restaurateurs returned to the practice. For some reason – world travel? the rebirth of gourmet dining? – some guests had begun to carry around their own portable grinders. Restaurants may have felt a need to respond if they were to appear sophisticated. And so, along with Beef Wellington and large padded menus, the pepper grinder made its appearance. If it seemed European now, so much the better. Evidently pepper mills were quite the thing in Los Angeles around 1955 because there were at least two manufacturers there.

Trouble was, though, when small grinders were placed on tables initially patrons had a way of walking off with the cute little things. Early adopter Peter Canlis found that when he began supplying each table with 4-inch-tall mills at his Charcoal Broiler in Honolulu, they all disappeared in the first three days.

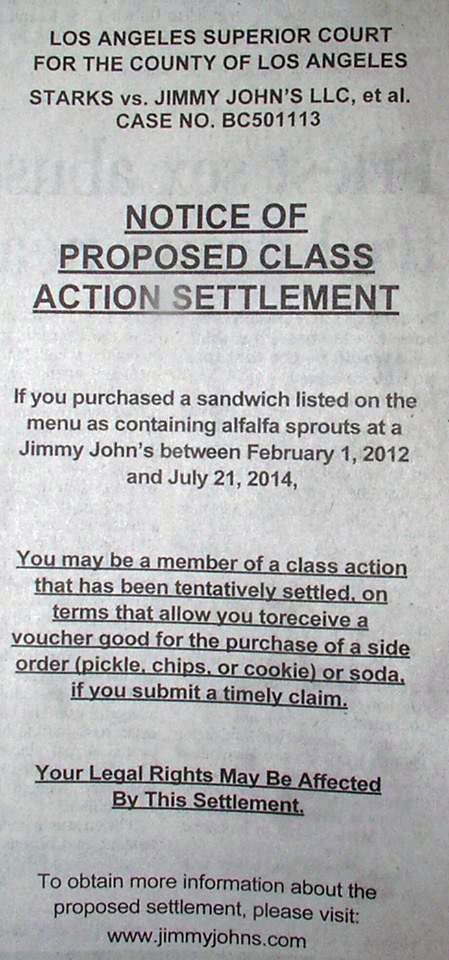

The solution: large, unpocketable grinders deployed only by the wait staff. How large? At the Town & Country restaurant in Dallas TX, which prided itself on Cuisine Français for discriminating diners, a special stand was required for propping a 9-foot pepper mill over the table. [pictured]

Beginning in the 1970s, pepper mills the size of fire plugs or in the shape of baseball bats became a source of humor and critique. Some also noted that pepper mills enabled servers to appear as though they were giving superior service in hopes of bigger tips. Mimi Sheraton objected to how restaurants pounced on diners with the pepper mill before they’d had a chance to even sample their food.

Now pepper mills have shrunken to a manageable size, criticism has died away, and it seems to be standard operation for restaurants of a certain price and service level to equip servers with them.

© Jan Whitaker, 2015

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.