In the depths of the Depression, in 1934, Harper & Bros. published a book of 304 photographs called Metropolis. Most of the photos were by Edward M. Weyer, Jr., an anthropologist who wanted to show how people in greater NYC lived. Captions were supplied by the popular writer Frederick Lewis Allen.

In a 2010 NY Times story the book was described as a “romantic masterpiece of street photography” composed of “moody black-and-white coverage of day-to-day life in New York in the ’30s. Beggars, snow-shoveling squads, schooner crews, railroad commuters, subway crowds, tenement life, tugboats, a sidewalk craps game. . .”

I find it particularly interesting that a major focus of the book was to contrast how different social classes lived, illustrated in part by where they ate lunch.

The central narrative follows employees of a company headed by a Mr. Roberts. He lives in a house on a 4-acre plot in Connecticut, commutes to New York, and employs a house maid whose duties include fixing his wife’s lunch each day. On the day he is being profiled Mr. Roberts eats a $1.00 table d’hôte lunch at his club (equal to $17 today). So frugal, Mr. R.

Mr. Roberts is visited by a Mr. Smith from out of town (shown above looking out hotel window). Mr. Smith “stands for all those who come to the city from a distance,” whether Los Angeles, Boston, or elsewhere. He is “reasonably well off.” Mr. Smith eats a $1.25 table d’hôte lunch – er, luncheon — in a dining room on a hotel roof (pictured). Prices are high there, making his meal a relative bargain. Had he wanted to splurge he could have ordered a Cocktail (.40), Lobster Thermidor ($1.25), and Cucumber Salad (.45) – total $2.10. I would guess that many visitors to New York tend to spend more on restaurants than natives.

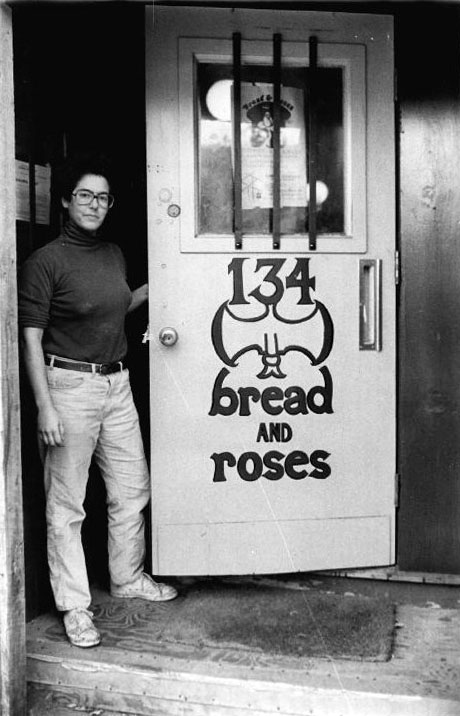

Mr. Roberts’ secretary, Miss Jordan, lives with her mother and brother in an apartment just off Riverside Drive. With a combined family income of less than $4,000 the three can barely afford their $125/month rent. She goes to lunch at a café (pictured) and orders To-Day’s Luncheon Special which consists of Tomato Juice, Corned Beef Hash with Poached Egg, Ice Cream, and Coffee, all for 40 cents. Frankly, I don’t see how she can afford to do this every day.

Miss O’Hara and Miss Kalisch transcribe dictation from other executives in the firm and each makes about $22.50 a week. Miss Kalisch lives in Astoria, Queens, and is married. Evidently she is pretending to be single in order to hold her job (her name is really Mrs. Rosenbloom). Miss O’Hara lives with her father in a somewhat decrepit apartment costing almost half her wages. Her father has been out of work for three years. The two women eat lunch at a drugstore counter (pictured) where they order Ham on Rye Sandwiches, Chocolate Cake, and Coffee (.30). I fear Miss O’Hara is living beyond her means if she does this often.

Miss Heilman, a young clerk, makes about $16.50 a week and is subject to occasional layoffs. She lives with her brother, his wife, and their two children in a 3-room apartment in Hoboken NJ, for which they pay $15/month. Like the other “girls” at the bottom of the totem pole she brings a sandwich and eats it in the office.

Mr. Smith, being on his own, must go out for dinner. Once again he chooses a hotel roof garden (pictured), where about half the guests are also out-of-towners. With a live orchestra and dancing, it is undoubtedly expensive. I’m guessing he went for the Cocktail and Lobster Thermidor this time.

© Jan Whitaker, 2013

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.