Driving around Connecticut a while back I noticed signs with the unfamiliar terms “lapizza” and “apizza.” Occasionally since then I’ve wondered what accounted for the deviation from the commonplace word “pizza.”

Thanks to a recent round of fundraising on Connecticut Public Television, when they featured showings of Pizza, A Love Story, I found out why pizza was spelled that way. Watching the show, I heard the word apizza pronounced – repeatedly – for effect. Can you say ah-BEETS? That pronunciation is Neapolitan dialect, a simplification of la pizza. New Haven CT is hailed as today’s apizza center of the U.S. by its dedicated fans who probably would refuse to even enter a pizza chain’s parking lot.

In fact, it’s impressive that in 1978, when Pizza Hut had expanded to over 3,000 units nationwide, none was listed in New Haven’s City Directory. However, there were at least 31 pizza places in that city then, ten of them with apizza as part of their name. One of the pizza restaurants in New Haven was that of Fancesco “Frank” Pepe, initially a baker, who started making pizza in 1925. [1960s postcard shown at top of page] Today Pepe’s Pizzeria Napoletana is a small New England chain that has won many awards.

Although the word apizza came into common usage in advertisements in Connecticut newspapers in the 1930s – not just in New Haven but also Bridgeport, Meriden, and other cities – it remains in use today in many of the state’s Italian restaurants. I haven’t run across any descriptions of the Connecticut apizza of earlier days, but it’s unlikely that it was the cheese-delivery vehicle that most Americanized pizza has become. In the early 20th century Neapolitan pizza was described as a somewhat puffy, foldable crust typically topped with cooked tomatoes, grated cheese, oregano, and/or anchovies.

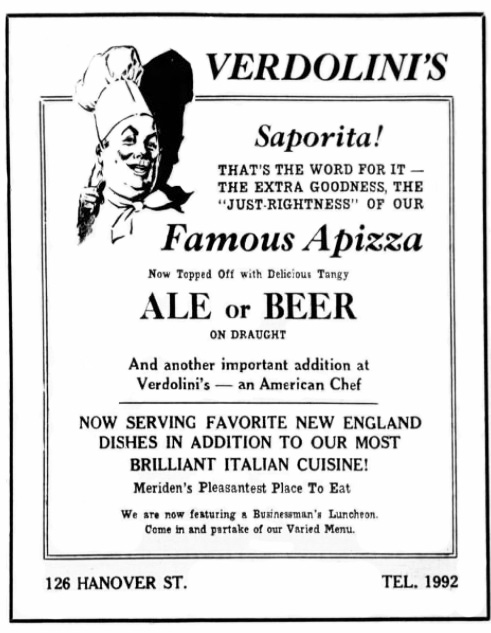

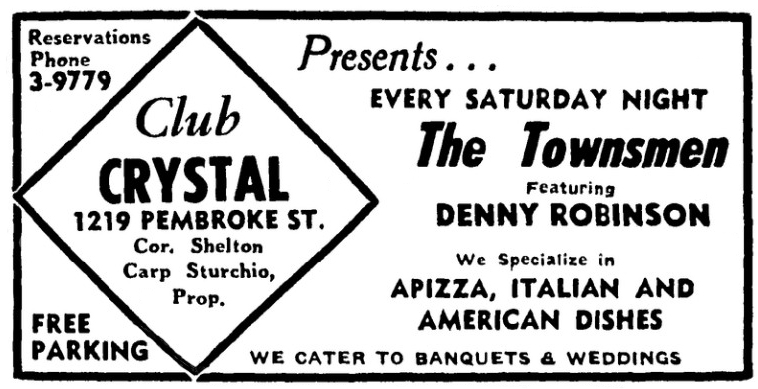

From the start in Connecticut and a few other parts of the Northeast, as well as California, pizza was take-out food, often bought at a bakery. But after Prohibition ended, it expanded into casual eating spots in Connecticut cities. Many of its purveyors ran taverns or other night spots, some of which featured it only on weekends. [below, Club Crystal, Bridgeport, 1940s] It was more of a snack than a meal, something to enjoy with friends. Beer was the favorite liquid accompaniment. As Meriden CT restaurant owner Vincent Verdolini put it in 1939, “beer to a lover of la pizza is like whipped cream to strawberry shortcake.”

Until the 1950s, most apizza consumers were Italian-Americans, many of them workers in Connecticut’s factories. Happily for them, pizza was inexpensive (in 1940, roughly 25¢ for small ones and 45¢ for large) and sellers delivered to workplaces. Early advertisements aimed at Italian speaking customers appeared in Italian-language newspapers such as La Sentinella in Bridgeport.

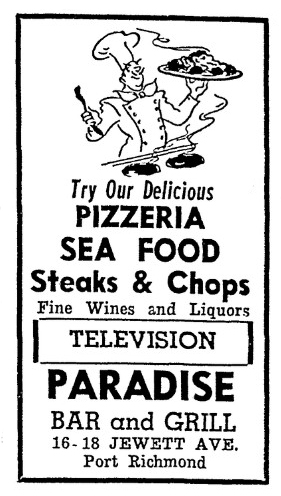

As I searched for the history of apizza in Connecticut, I happened upon another name for pizza, one that really surprised me because its meaning has shifted: pizzeria. Now a common name for a pizza parlor, at one time it was a word for pizza itself, as is evident in the advertisement for “delicious pizzeria, 25¢” at Frieda’s in Asbury Park NJ in 1936, shown above, or at the Paradise Bar and Grill on Staten Island in 1947 below.

For several decades restaurant chains have dominated the pizza market, making it all the more interesting that apizza, the word and the food, has survived.

© Jan Whitaker, 2022

It seems as though almost all of history’s food forces have cooperated to give cheese top billing in restaurant meals today. Only one cheesy custom failed to catch on, that of finishing a meal with cheese and fruit as was done in small French and Italian restaurants in the later 19th century. Craig Claiborne argued in 1965 that even the best New York restaurants didn’t know how to handle the cheese course. They had poor selections which tended to be old, overripe, or served too cold. One restaurant admitted their chef was in the habit of popping cheese straight from the fridge into the oven to soften it. Restaurateurs that Claiborne interviewed insisted that Americans didn’t like cheese after a meal. I’d agree that most prefer their after-dinner cheese in the form of cheesecake.

It seems as though almost all of history’s food forces have cooperated to give cheese top billing in restaurant meals today. Only one cheesy custom failed to catch on, that of finishing a meal with cheese and fruit as was done in small French and Italian restaurants in the later 19th century. Craig Claiborne argued in 1965 that even the best New York restaurants didn’t know how to handle the cheese course. They had poor selections which tended to be old, overripe, or served too cold. One restaurant admitted their chef was in the habit of popping cheese straight from the fridge into the oven to soften it. Restaurateurs that Claiborne interviewed insisted that Americans didn’t like cheese after a meal. I’d agree that most prefer their after-dinner cheese in the form of cheesecake. Cheese has been a staple food in American eating places probably since the first tavern opened. Regular meals were served only at stated hours but hungry customers could get cheese and crackers at the bar whatever the hour. For “Gentlemen en’passant,” the Union Coffee House in Boston promised in 1785 that it could always furnish the basics of life: oysters, English cheese, and London Porter. Across the river in Cambridge, the renowned

Cheese has been a staple food in American eating places probably since the first tavern opened. Regular meals were served only at stated hours but hungry customers could get cheese and crackers at the bar whatever the hour. For “Gentlemen en’passant,” the Union Coffee House in Boston promised in 1785 that it could always furnish the basics of life: oysters, English cheese, and London Porter. Across the river in Cambridge, the renowned  Cheeseburgers were a product of the fast food industry of the 1920s, claimed as inventions by both the Rite Spot of Southern California and the Little Tavern of Louisville. Strange there aren’t thousands of other contenders because what was there to invent, really? Cheeseburgers were strongly associated with Southern California before WWII — Bob’s Big Boy of LA introduced cheeseburgers in 1937. Another step forward came in the 1930s when a bill was introduced in the Wisconsin legislature requiring restaurants and cafes to serve 2/3 oz. of Wisconsin cheese with every meal costing 25 cents or more. In the same decade Kraft Cheese was among major food producers providing restaurants with standardized recipe cards.

Cheeseburgers were a product of the fast food industry of the 1920s, claimed as inventions by both the Rite Spot of Southern California and the Little Tavern of Louisville. Strange there aren’t thousands of other contenders because what was there to invent, really? Cheeseburgers were strongly associated with Southern California before WWII — Bob’s Big Boy of LA introduced cheeseburgers in 1937. Another step forward came in the 1930s when a bill was introduced in the Wisconsin legislature requiring restaurants and cafes to serve 2/3 oz. of Wisconsin cheese with every meal costing 25 cents or more. In the same decade Kraft Cheese was among major food producers providing restaurants with standardized recipe cards. It was after WWII that cheese spread its melted gooeyness everywhere — on

It was after WWII that cheese spread its melted gooeyness everywhere — on

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.