There are a couple of reasons why I’ve been thinking about glass ceilings in restaurants this week. I took a look at the total number of visits to my top posts and, apart from the various Taste of a decade posts which draw a lot of traffic, Swingin’ at Maxwell’s Plum is #1. An elaborate stained glass ceiling was one of the most striking features of Maxwell’s Plum in New York City, and also at the San Francisco Plum (pictured) which opened in 1981.

There are a couple of reasons why I’ve been thinking about glass ceilings in restaurants this week. I took a look at the total number of visits to my top posts and, apart from the various Taste of a decade posts which draw a lot of traffic, Swingin’ at Maxwell’s Plum is #1. An elaborate stained glass ceiling was one of the most striking features of Maxwell’s Plum in New York City, and also at the San Francisco Plum (pictured) which opened in 1981.

The second reason is that last Sunday I went to the antique paper show Papermania in Hartford CT and bought a 1970s-era menu from a pizza restaurant in St. Louis that I used to go to but had forgotten all about. It too had a glass ceiling though, as I recall, it was fairly plain. I won’t name the restaurant but will say that it was located in the vicinity of Washington University where I went to graduate school and there was a second place in Creve Coeur.

On one occasion I went to the city location with a group of friends and we witnessed a kind of free floor show – only it took place inside the glass ceiling. We heard the sounds first, of little claw feet scratching on glass. Then we looked up. We saw silhouettes of a legion of four-footed creatures with long tails which were furiously scrimmaging above us, as though playing a game of football. We laughed, considered leaving, but ended up staying. If the management noticed anything amiss they certainly didn’t show it. No one came over to explain away the incident (not that I know how you’d do that), no one offered us free drinks, nothing!

The menu from this restaurant which I just acquired displays on its cover a pledge of quality accompanied by the signature of the restaurant’s owner. One of the sentences jumps out at me: “More ingredients go into our pizza than the normal recipe calls for.” Yikes, say no more!

© Jan Whitaker, 2010

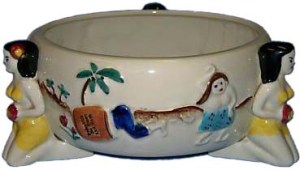

Don ran into trouble with the postwar longshoremen’s strike and decided to limit his Honolulu Beachcomber to a drinking spot. By the early 1960s he was also in the restaurant business, operating a South Seas Cabaret Restaurant, a Colonel’s Plantation Steak House, a Colonel’s Coffee House, and at least one restaurant boat. Cora’s popular Chicago Don the Beachcomber was named one of the top 50 US restaurants in 1947. She soon opened another location in Palm Springs and by 1972, when it was acquired by Getty Financial, the chain had 6 or 7 units.

Don ran into trouble with the postwar longshoremen’s strike and decided to limit his Honolulu Beachcomber to a drinking spot. By the early 1960s he was also in the restaurant business, operating a South Seas Cabaret Restaurant, a Colonel’s Plantation Steak House, a Colonel’s Coffee House, and at least one restaurant boat. Cora’s popular Chicago Don the Beachcomber was named one of the top 50 US restaurants in 1947. She soon opened another location in Palm Springs and by 1972, when it was acquired by Getty Financial, the chain had 6 or 7 units.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.