A few days ago I read a fascinating article by Jill Lepore in the New Yorker. It was about Ruth Stout, author of How to Have a Green Thumb, Without an Aching Back, originally published in 1955. It has been reissued and is still quite popular.

There were many engaging aspects to Stout’s life, such as her affair with the radical Scott Nearing, her career as a writer, the fact that her brother was the mystery novelist Rex Stout who created Nero Wolfe, her involvement with ‘no-plow’ gardening, and the fact that lived to be 96. [Below: Ruth in 1923, age 39.]

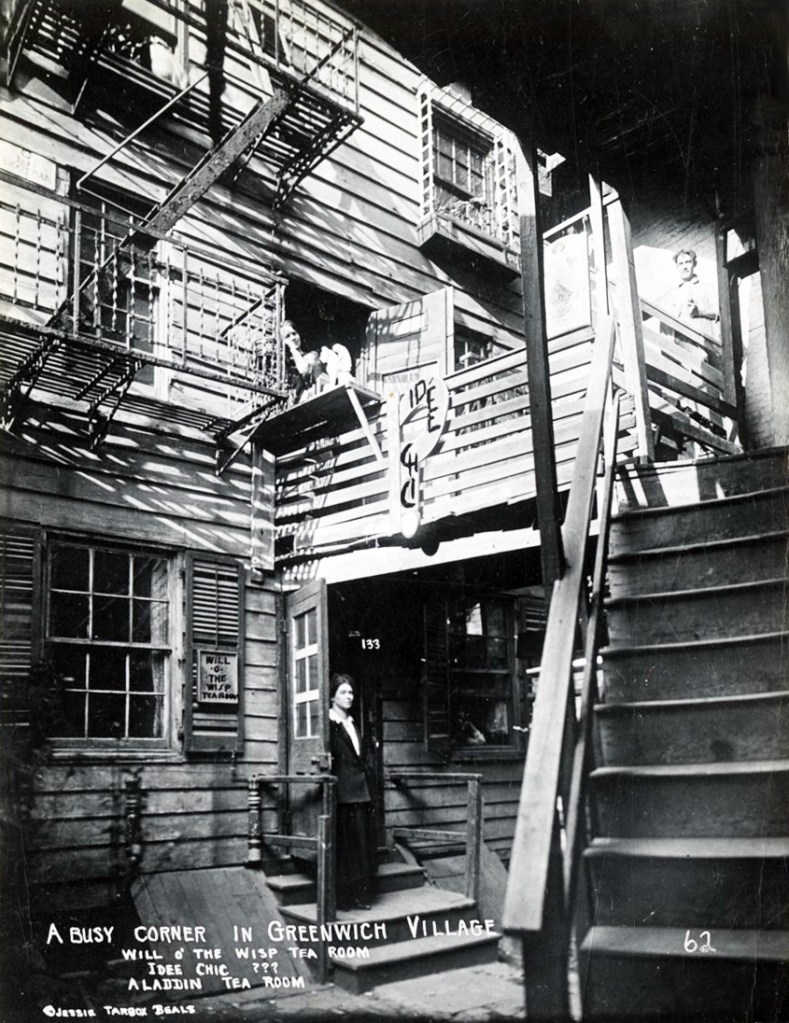

But what especially interested me was that Stout had been briefly involved in owning and running two tea rooms in Greenwich Village around 1917. They didn’t last long, but that was true — almost typical — of many tea rooms.

The first was the Will o’ the Wisp which she opened with a family friend. It was appropriately named, being short-lived. It was ridiculed by the New-York Tribune in a 1917 story about an imaginary visitor from afar searching NYC for the “real Bohemia.” He and the writer go to “the Wisp” (as it was known), where the “young ladies” (actually about 32 and 50 years old) that operated it invite them to come back the next night and help wash dishes around 1 or 2 a.m. The sardonic piece ends with the trite observation that Bohemia is a fantasy.

If the Tribune writer had known that the two women running the Wisp were both from small towns in Kansas, that would have been another sign of how misplaced his dismissive attitude was. They actually represented the adventurousness and talent of many New York transplants. In this case they were writers, world travelers, and free spirits.

The Greenwich Village tearooms before World War I served mainly as hangouts for local residents, many of whom were artists and who liked to gather with friends in the evening. Alas, they didn’t spend much, so the advent of visitors from outside the Village was a financial boon. The Wisp tagged itself in advertising as a place for writers, “the poets’ favorite,” not a slogan likely to draw the masses.

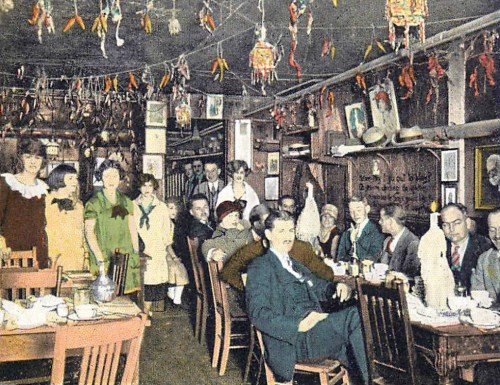

As the photo at the top shows (by the Village’s photographer Jessie Tarbox Beals), tea rooms were plentiful, with three in the building in this photo. And the building itself is none too impressive, even looks somewhat structurally unsound. The Wisp is on the ground floor.

Not much later, or maybe simultaneously with the Will o’ the Wisp, Ruth opened a second Village tea room called The Klicket, this one with dancing. The Quill, the Village’s magazine, promoted it saying, “Ruth Stout’s ‘Klicket’ has a good floor, and say! Ruth CAN cook!” No doubt she was amused by that since she wasn’t much of a cook.

At the Klicket, Ruth found herself keeping even later hours, but there was little monetary reward.

As she indicated in her advertisement she mainly hoped her customers would end the evening by paying for their tea. It was not a financial success and she kept it going only for about a year.

In a 1917 book about the Village, author Anna Alice Chapin outlined the “phases” which the Village was going through, which included not only “the tea-shop epidemic,” but also psychoanalysis, arts and crafts, masquerade balls, and support for labor activism and anarchy. Ruth took up the call to radicalism. She and Rex were on the editorial board of a leading socialist-communist periodical The New Masses. She also visited Russia as a Quaker volunteer helping alleviate famine there in 1923 and became a helper and romantic partner of Scott Nearing for several years, living with him on his farm.

She published four books in the 1950s and 1960s, including her garden book and Company Coming: Six Decades of Hospitality, Do-it-yourself and Otherwise, in which she mentioned her tea rooms. Until her death in 1980 she spent her elder years in Connecticut where she and her husband Fred Rossiter had acreage.

© Jan Whitaker, 2025

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.