Herbert M. Kinsley, a leading Chicago restaurateur of the later 19th century, faced many obstacles. Like many in the restaurant business, his was a high-energy career full of zigs and zags. Born in Canton MA in 1831, he began working at a young age, picking up a skill of great value for his future, bookkeeping. After several years in retailing he entered hotel stewarding in Cincinnati, then Chicago and Canada.

Herbert M. Kinsley, a leading Chicago restaurateur of the later 19th century, faced many obstacles. Like many in the restaurant business, his was a high-energy career full of zigs and zags. Born in Canton MA in 1831, he began working at a young age, picking up a skill of great value for his future, bookkeeping. After several years in retailing he entered hotel stewarding in Cincinnati, then Chicago and Canada.

He returned to Chicago in the early 1860s and was employed in hotels. In 1865 he acquired the restaurant in Chicago’s Opera House where he established a reputation as a skilled restaurateur, but lost money. He sold the business, spent some time setting up railroad hotels and dining cars, and then in 1868 started another restaurant in Chicago on Washington Street. The following year he reportedly also ran the first Pullman dining car, on the Chicago-Northwestern railway. In 1870 he opened a restaurant in the new planned community of Riverside IL, which likely went out of business when the development faltered shortly after its inception, about the same time his Washington Street restaurant was badly damaged in the Great Fire of 1871. He once again left Chicago, to open hotels on the Baltimore & Ohio line.

When he returned to Chicago he took over a restaurant called Brown’s, in 1874 during a nationwide depression. A few months later he closed it, announcing, “The expenses of a fashionable restaurant just now are too great, and the receipts too small, to warrant keeping it open longer.” The furniture and fixtures were auctioned and he leased out the premises, keeping just enough space to continue his catering business.

A few years later he dared to try again and opened a new place, finally meeting with success. By 1884 Kinsley’s was considered Chicago’s finest restaurant and society’s first choice for catering dinners and parties. In 1885 he built a new four-story restaurant on Adams Street. Short of capital to complete this costly venture, he turned to one of Chicago’s noted restaurant backers, the liquor distributor Chapin & Gore.

A few years later he dared to try again and opened a new place, finally meeting with success. By 1884 Kinsley’s was considered Chicago’s finest restaurant and society’s first choice for catering dinners and parties. In 1885 he built a new four-story restaurant on Adams Street. Short of capital to complete this costly venture, he turned to one of Chicago’s noted restaurant backers, the liquor distributor Chapin & Gore.

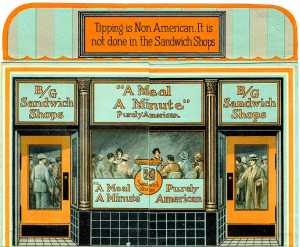

Kinsley took positions on the issues of race and tipping that were at odds with many restaurateurs of his time. He declared in 1880s he was always willing to serve Afro-American customers, thought black waiters were among the finest, and found tipping a reasonable system of remuneration that encouraged good service. He was fond of large silver serving pieces (coffee urn pictured) and authored a book for Gorham Silver on chafing dish recipes.

In 1891, he and son-in-law Gustav Baumann opened the new and elegant Holland House hotel in New York City, hiring a Delmonico veteran as steward, importing a French chef, and sinking $350,000 into the wine cellar. In 1892 architect Daniel Burnham hired Kinsley to plot the logistics of restaurants for the Chicago World’s Fair. That same year Kinsley’s was the site of a lavish inaugural dinner for the Fair that hosted the Vice President of the US and 6 cabinet members, former President Rutherford Hayes, 27 governors, 4 supreme court justices, 17 ministers of foreign governments, and countless dignitaries. After H.M.’s untimely death in 1894, his Chicago restaurant continued under new management until 1905 when the building was razed. For years to come it would be remembered as a symbol of a lost era.

In 1891, he and son-in-law Gustav Baumann opened the new and elegant Holland House hotel in New York City, hiring a Delmonico veteran as steward, importing a French chef, and sinking $350,000 into the wine cellar. In 1892 architect Daniel Burnham hired Kinsley to plot the logistics of restaurants for the Chicago World’s Fair. That same year Kinsley’s was the site of a lavish inaugural dinner for the Fair that hosted the Vice President of the US and 6 cabinet members, former President Rutherford Hayes, 27 governors, 4 supreme court justices, 17 ministers of foreign governments, and countless dignitaries. After H.M.’s untimely death in 1894, his Chicago restaurant continued under new management until 1905 when the building was razed. For years to come it would be remembered as a symbol of a lost era.

© Jan Whitaker, 2008

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.