Don Dickerman was obsessed with pirates. He took every opportunity to portray himself as one, beginning with a high school pirate band. As an art student in the teens he dressed in pirate garb for Greenwich Village costume balls. Throughout his life he collected antique pirate maps, cutlasses, blunderbuses, and cannon. His Greenwich Village nightclub restaurant, The Pirates’ Den, where colorfully outfitted servers staged mock battles for guests, became nationally known and made him a minor celebrity.

Don Dickerman was obsessed with pirates. He took every opportunity to portray himself as one, beginning with a high school pirate band. As an art student in the teens he dressed in pirate garb for Greenwich Village costume balls. Throughout his life he collected antique pirate maps, cutlasses, blunderbuses, and cannon. His Greenwich Village nightclub restaurant, The Pirates’ Den, where colorfully outfitted servers staged mock battles for guests, became nationally known and made him a minor celebrity.

It might seem that Don’s buccaneering interests were commercially motivated except that he often dressed as a pirate in private life, owned a Long Island house associated with pirate lore, formed a treasure-hunting club, and spent a small fortune collecting pirate relics. He was a staff artist on naturalist William Beebe’s West Indies expedition in 1925, and in 1940 had a small part in Errol Flynn’s pirate movie The Sea Hawk.

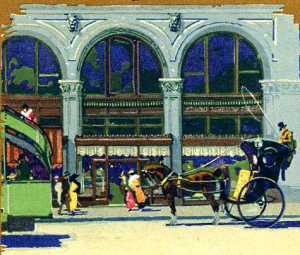

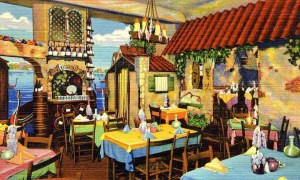

Over time he ran five clubs and restaurants in New York City. After failing to make a living as a toy designer and children’s book illustrator, he opened a tea room in the Village primarily as a place to display his hand-painted toys. It became popular, expanded, and around 1917 he transformed it into a make-believe pirates’ lair where guests entered through a dark, moldy basement. Its fame began to grow, particularly after 1921 when Douglas Fairbanks recreated its atmospheric interior for his movie The Nut. He also ran the Blue Horse (pictured), the Heigh-Ho (where Rudy Vallee got his start), Daffydill (financed by Vallee), and the County Fair.

Over time he ran five clubs and restaurants in New York City. After failing to make a living as a toy designer and children’s book illustrator, he opened a tea room in the Village primarily as a place to display his hand-painted toys. It became popular, expanded, and around 1917 he transformed it into a make-believe pirates’ lair where guests entered through a dark, moldy basement. Its fame began to grow, particularly after 1921 when Douglas Fairbanks recreated its atmospheric interior for his movie The Nut. He also ran the Blue Horse (pictured), the Heigh-Ho (where Rudy Vallee got his start), Daffydill (financed by Vallee), and the County Fair.

On a Blue Horse menu of the 1920s Don’s mother is listed as manager. Among the dishes featured at this jazz club restaurant were Golden Buck, Chicken a la King, Tomato Wiggle, and Tomato Caprice. Drinks (non-alcoholic) included Pink Goat’s Delight and Blue Horse’s Neck. Ice cream specials also bore whimsical names such as Green Goose Island and Mr. Bogg’s Castle. At The Pirates’ Den a beefsteak dinner cost a hefty $1.25. Also on the menu were chicken salad, sandwiches, hot dogs, and an ice cream concoction called Bozo’s Delight. A critic in 1921 concluded that, based on the sky-high menu tariffs and the “punk food,” customers there really were at the mercy of genuine pirates.

On a Blue Horse menu of the 1920s Don’s mother is listed as manager. Among the dishes featured at this jazz club restaurant were Golden Buck, Chicken a la King, Tomato Wiggle, and Tomato Caprice. Drinks (non-alcoholic) included Pink Goat’s Delight and Blue Horse’s Neck. Ice cream specials also bore whimsical names such as Green Goose Island and Mr. Bogg’s Castle. At The Pirates’ Den a beefsteak dinner cost a hefty $1.25. Also on the menu were chicken salad, sandwiches, hot dogs, and an ice cream concoction called Bozo’s Delight. A critic in 1921 concluded that, based on the sky-high menu tariffs and the “punk food,” customers there really were at the mercy of genuine pirates.

As the Depression deepened business evaporated, leading Don to declare bankruptcy in 1932. A few years later he turned up in Miami, running a new Pirates’ Den, and next in Washington D.C. where he opened another Pirates’ Den on K Street in Georgetown in 1939. In 1940 he opened yet another Pirates’ Den, at 335 N. La Brea in Los Angeles, which was co-owned by Rudy Vallee, Bob Hope, and Bing Crosby among others. In the photograph, Don is shown at the Los Angeles Pirates’ Den with wife #5 (photo courtesy of Don’s granddaughter Kathleen P.).

As the Depression deepened business evaporated, leading Don to declare bankruptcy in 1932. A few years later he turned up in Miami, running a new Pirates’ Den, and next in Washington D.C. where he opened another Pirates’ Den on K Street in Georgetown in 1939. In 1940 he opened yet another Pirates’ Den, at 335 N. La Brea in Los Angeles, which was co-owned by Rudy Vallee, Bob Hope, and Bing Crosby among others. In the photograph, Don is shown at the Los Angeles Pirates’ Den with wife #5 (photo courtesy of Don’s granddaughter Kathleen P.).

© Jan Whitaker, 2008

Half the population of the largest cities is foreign born. San Francisco continues to attract adventurers and French chefs. The Civil War brings wealth to Northern industrialists and speculators, encouraging high living. With German immigration going strong, beer gains in popularity as do “free” lunches. Saloons prosper and the anti-alcohol movement loses ground as the states where liquor is prohibited shrink from thirteen to six, then to one. Cities grow as young single men pour into urban areas. Restaurants spring up to feed them and cheap lunch rooms proliferate, offsetting the high prices prevalent during and after the war. By the end of the decade, one estimate puts the number of eating places in NYC at an astonishing 5,000 or 6,000.

Half the population of the largest cities is foreign born. San Francisco continues to attract adventurers and French chefs. The Civil War brings wealth to Northern industrialists and speculators, encouraging high living. With German immigration going strong, beer gains in popularity as do “free” lunches. Saloons prosper and the anti-alcohol movement loses ground as the states where liquor is prohibited shrink from thirteen to six, then to one. Cities grow as young single men pour into urban areas. Restaurants spring up to feed them and cheap lunch rooms proliferate, offsetting the high prices prevalent during and after the war. By the end of the decade, one estimate puts the number of eating places in NYC at an astonishing 5,000 or 6,000.

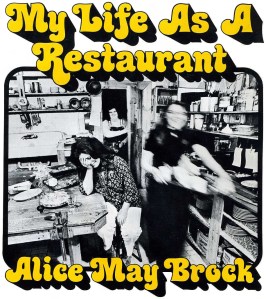

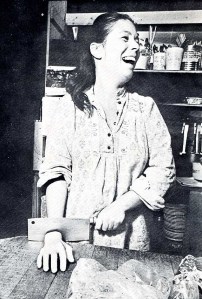

In interviews and in her two books Alice espoused the value of fresh ingredients, garlic, meals with friends, and an experimental approach to cooking. Her words convey a free-wheeling, irreverent outlook. Some examples:

In interviews and in her two books Alice espoused the value of fresh ingredients, garlic, meals with friends, and an experimental approach to cooking. Her words convey a free-wheeling, irreverent outlook. Some examples:

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.