A “faux” want-ad for a young clerk, allegedly placed by “Iscariot Grasp, 1 Brokers’ Alley,” was published in New York in 1849. It represents a humorous take on Puritanical notions of morality of that time. Evidently an upstanding young man then was supposed to confine his dining to home. If he wanted the clerk job he had to promise to reside with his parents and not to frequent “oyster-cellars, porter-houses, theatres, balls, ten-pin alleys, billiard rooms, sweat-boards [a dice game], raffles for poultry or game, restaurants, confectioners, steam-boats, Coney-Island, Rockaway or Saratoga.”

A “faux” want-ad for a young clerk, allegedly placed by “Iscariot Grasp, 1 Brokers’ Alley,” was published in New York in 1849. It represents a humorous take on Puritanical notions of morality of that time. Evidently an upstanding young man then was supposed to confine his dining to home. If he wanted the clerk job he had to promise to reside with his parents and not to frequent “oyster-cellars, porter-houses, theatres, balls, ten-pin alleys, billiard rooms, sweat-boards [a dice game], raffles for poultry or game, restaurants, confectioners, steam-boats, Coney-Island, Rockaway or Saratoga.”

Between courses: keep out of restaurants

Filed under miscellaneous

The Automat, an East Coast oasis

In the late 19th century owners of large popular-price restaurants began to look for ways to cut costs and eliminate waiters. The times were hospitable to mechanical solutions and in 1902 automatic restaurants opened in Philadelphia (pictured below) and New York. In both cities, a clever coin-operated set-up – and a name – were imported from Germany. There was, however, a striking difference between the two operations. The Philadelphia Automat, run by Joseph Horn and Frank Hardart, served no alcoholic beverages, while the New York Automat, true to its European origins, did.

In the late 19th century owners of large popular-price restaurants began to look for ways to cut costs and eliminate waiters. The times were hospitable to mechanical solutions and in 1902 automatic restaurants opened in Philadelphia (pictured below) and New York. In both cities, a clever coin-operated set-up – and a name – were imported from Germany. There was, however, a striking difference between the two operations. The Philadelphia Automat, run by Joseph Horn and Frank Hardart, served no alcoholic beverages, while the New York Automat, true to its European origins, did.

The Automat in NYC was owned by James Harcombe, who in the 1890s had acquired Sutherland’s, one of the city’s old landmark restaurants located on Liberty Street. The Harcombe Restaurant Company’s Automat was at 830 Broadway, near Union Square. Reportedly costing more than $75,000 to install, it was a marvel of invention decorated with inlaid mirror, richly colored woods, and German proverbs. It served forth sandwiches and soups, dishes such as fish chowder and lobster Newburg, and ice creams. Beer, cocktails, and cordials flowed from its faucets. A bit too freely. The Automat’s staff had to keep a sharp lookout for young boys dropping coins into the liquor slots.

The Automat in NYC was owned by James Harcombe, who in the 1890s had acquired Sutherland’s, one of the city’s old landmark restaurants located on Liberty Street. The Harcombe Restaurant Company’s Automat was at 830 Broadway, near Union Square. Reportedly costing more than $75,000 to install, it was a marvel of invention decorated with inlaid mirror, richly colored woods, and German proverbs. It served forth sandwiches and soups, dishes such as fish chowder and lobster Newburg, and ice creams. Beer, cocktails, and cordials flowed from its faucets. A bit too freely. The Automat’s staff had to keep a sharp lookout for young boys dropping coins into the liquor slots.

While the Philadelphia Automat thrived, the New York counterpart ran into financial difficulties shortly after opening, possibly because of a poor location. It advertised in an NYU student magazine in 1904: “Europe’s Unique Electric Self-serving Device for Lunches and Beverages. No Waiting. No Tipping. Open Evenings Until Midnight.” The disappearance of the Harcombe Automat ca. 1910 seemed to fulfill pessimistic views that an automatic restaurant couldn’t succeed in New York, allegedly because machinery would malfunction and customers would cheat by feeding it slugs.

Undeterred by the first Automat’s fate, Horn & Hardart moved into New York in 1912, opening an Automat of their own manufacture at Broadway and 46th Street (pictured). It turned out that New Yorkers did indeed use slugs, especially in 1935 when 219,000 were inserted into H&H slots. But despite this, the automatic restaurant prospered, expanded, and became a New York institution. By 1918 there were nearly 50 Automats in the two major cities, and eventually a few in Boston. Horn & Hardart tried Automats in Chicago in the 1920s but they were a failure. On an inspection tour in Chicago, Joseph Horn noted problems such as weak coffee, “figs not right,” and “lem. meringue very bad.”

Undeterred by the first Automat’s fate, Horn & Hardart moved into New York in 1912, opening an Automat of their own manufacture at Broadway and 46th Street (pictured). It turned out that New Yorkers did indeed use slugs, especially in 1935 when 219,000 were inserted into H&H slots. But despite this, the automatic restaurant prospered, expanded, and became a New York institution. By 1918 there were nearly 50 Automats in the two major cities, and eventually a few in Boston. Horn & Hardart tried Automats in Chicago in the 1920s but they were a failure. On an inspection tour in Chicago, Joseph Horn noted problems such as weak coffee, “figs not right,” and “lem. meringue very bad.”

Part of the lore of the Automat derives from the unexpected forms of sociability it inspired among strangers. Others found in it a unique entertaining concept. Jack Benny hosted a black tie dinner in a New York Automat for 500 friends in 1960, but he was scarcely the first to come up with the idea. As early as 1903 a Philadelphia hostess rented that city’s Automat for a soirée, hiring a caterer to replace meatloaf and coffee with terrapin and champagne. In 1917 a New York bohemian group calling themselves “The Tramps” took over the Broadway Automat for a dance party, inserting in the food compartments numbered slips corresponding to dance partners. For most customers, though, the Automat meant cheap food and possibly a leisurely place to kill time and watch the parade of humanity.

The Automats hit their peak in the mid-20th century. Slugs aside, the Depression years were better for business than the wealthier 1960s and 1970s when some units were converted to Burger Kings. In 1933 H&H hired Francis Bourdon, the French chef at the Sherry Netherland (fellow chefs called him “L’Escoffier des Automats”). In 1969 Philadelphia’s first Automat closed, being declared “a museum piece, inefficient and slow, in a computerized world.” That left two in Philadelphia and eight in NYC. The last New York Automat, at East 42nd and 3rd Ave, closed in 1991.

The Automats hit their peak in the mid-20th century. Slugs aside, the Depression years were better for business than the wealthier 1960s and 1970s when some units were converted to Burger Kings. In 1933 H&H hired Francis Bourdon, the French chef at the Sherry Netherland (fellow chefs called him “L’Escoffier des Automats”). In 1969 Philadelphia’s first Automat closed, being declared “a museum piece, inefficient and slow, in a computerized world.” That left two in Philadelphia and eight in NYC. The last New York Automat, at East 42nd and 3rd Ave, closed in 1991.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Filed under chain restaurants

Good eaters: James Beard

James Beard enjoyed eating out – in fact much of his life revolved around restaurants. When he was a child his mother often took him to places such as the Royal Bakery in his hometown of Portland OR and Tait’s in San Francisco (pictured). Although he was an accomplished cook, cooking teacher, and author of over 20 cookbooks, like many a New Yorker he patronized restaurants frequently, including Maillard’s, Longchamps, and the Automat. At one point, when he had become more prosperous, he ate almost nightly for a solid month at one of his regular haunts, the Coach House near his home in Greenwich Village, where his favorite dishes included corn sticks, black bean soup, and mutton chops. One summer in 1953 he managed a restaurant on Nantucket.

James Beard enjoyed eating out – in fact much of his life revolved around restaurants. When he was a child his mother often took him to places such as the Royal Bakery in his hometown of Portland OR and Tait’s in San Francisco (pictured). Although he was an accomplished cook, cooking teacher, and author of over 20 cookbooks, like many a New Yorker he patronized restaurants frequently, including Maillard’s, Longchamps, and the Automat. At one point, when he had become more prosperous, he ate almost nightly for a solid month at one of his regular haunts, the Coach House near his home in Greenwich Village, where his favorite dishes included corn sticks, black bean soup, and mutton chops. One summer in 1953 he managed a restaurant on Nantucket.

He preferred restaurants that were “homey” and where he was known and liked, such as the Coach House and Quo Vadis. At the latter he became good friends with owners Bruno Caravaggi and Gino Robusti with whom he shared a love of opera. As a young man (pictured, age 19) he prepared for a musical career at London’s Royal Academy of Music. He said that his early performance training helped him with radio and TV appearances.

He preferred restaurants that were “homey” and where he was known and liked, such as the Coach House and Quo Vadis. At the latter he became good friends with owners Bruno Caravaggi and Gino Robusti with whom he shared a love of opera. As a young man (pictured, age 19) he prepared for a musical career at London’s Royal Academy of Music. He said that his early performance training helped him with radio and TV appearances.

In 1956 he issued his list of the country’s best restaurants, revealing a fondness for clubby male establishments and for places that were friendly — though usually expensive: Le Pavillon, ‘21,’ Quo Vadis (NYC); Jack’s (SF); Locke-Ober (Boston, pictured); Perino’s, Musso & Frank (Los Angeles); London Chop House (Detroit); and Walker Bros. Pancake House (Portland).

Restaurants also figured prominently in his professional life. He served as a consultant for restaurants in NY and Philadelphia, including the Four Seasons. For years he wrote a column on restaurants for the Los Angeles Times in which he touted places as diverse as Quo Vadis and Maxwell’s Plum in NYC and the Skyline Drive-In in Portland OR (“they make a whale of a good hamburger”). Despite occasional harsh opinions expressed about women in his 1950s barbecue cookbook days (“They should never be allowed to mix drinks.”), in later years he hailed Berkeley CA restaurateurs Alice Waters at Chez Panisse and Suzy Nelson, co-owner of The Fourth Street Grill.

He advised men on cooking and ways of suavely handling their culinary affairs, being careful, even when promoting French cuisine, to keep a down-to-earth tone. He disavowed the term gourmet, claiming he was definitely not one. In a review of Maxwell’s Plum he declared, “Not being a highbrow about food, I appreciate a really good hamburger or chili as much as a velvety quenelle or a rich pâté en croute.”

In a column he wrote for the National Brewing Company of Baltimore he urged discontented diners to stand up for good food, suggesting, “The only way to combat the stupid treatment of food in many restaurants is to be firm about sending food back to the kitchen whenever it is not right.” If asked how your dinner is, he insisted, do not say (if it was bad), “Oh very good, thank you.” In another piece he chided “mannerless” diners who make multiple reservations with the intention of deciding later which to honor. “When you dine out you have a certain responsibility to the management,” he wrote, explaining that no-shows seriously undermine small restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Filed under guides & reviews, proprietors & careers

Basic fare: waffles

In the early 19th century Philadelphians enjoyed driving their carriages to the falls on the Schuykill River, the area now known as East Falls, then lined with hotels and restaurants. Eating places there specialized in a favorite dish associated with Philadelphia long before the advent of cheese steaks, namely catfish and waffles. (I’d like to believe that the dish did not include maple syrup.)

In the early 19th century Philadelphians enjoyed driving their carriages to the falls on the Schuykill River, the area now known as East Falls, then lined with hotels and restaurants. Eating places there specialized in a favorite dish associated with Philadelphia long before the advent of cheese steaks, namely catfish and waffles. (I’d like to believe that the dish did not include maple syrup.)

Jumping ahead some 50 years, waffles also turn up again in Philadelphia as a featured specialty at a Civil War fundraiser in which an old-time kitchen recreated the food and cooking methods of early German settlers. While gazing at souvenirs such as Benjamin Franklin’s desk and a copper kettle used to make coffee for Revolutionary War soldiers, diners could indulge themselves with buttered waffles with sugar and cinnamon, sausages, or “omelette etwas” (scrambled eggs).

Of course waffles could be found in many restaurants over the past 200 years but they seem to have been especially popular in certain places and times. The “Wild West” was well supplied with waffle kitchens and houses. In mining camps and early settlements in Oregon, California, and Colorado waffles turn up on many menus in the 1880s and 1890s. Only in the West was the term “waffle foundry” used to describe lunch rooms like those in Los Angeles where in 1894 “a large waffle, swimming in melted butter and syrup is served for ten cents.”

Well into the 20th century waffles were familiar fare in boom towns such as Anchorage, Alaska, and the oilfields of Oklahoma. Around 1915 two young women from Seattle decided to seek their fortune in Alaska with the Two Girls Waffle House (pictured). In what was not much more than a shack with a canvas roof they could handle only eight customers at the counter. But after a year they had made enough money from railroad construction workers to build a permanent structure. A similar success story could be told about the two young men who ran the Kansas City Waffle House in Drumright, Oklahoma, before graduating to a bigger enterprise in Tulsa.

Well into the 20th century waffles were familiar fare in boom towns such as Anchorage, Alaska, and the oilfields of Oklahoma. Around 1915 two young women from Seattle decided to seek their fortune in Alaska with the Two Girls Waffle House (pictured). In what was not much more than a shack with a canvas roof they could handle only eight customers at the counter. But after a year they had made enough money from railroad construction workers to build a permanent structure. A similar success story could be told about the two young men who ran the Kansas City Waffle House in Drumright, Oklahoma, before graduating to a bigger enterprise in Tulsa.

Waffles were also a staple of tea rooms in the early 20th century. In places as varied as big city afternoon tea haunts and humble eateries in old New England homesteads, waffles attracted patrons. In 1917 New Yorkers could choose among the Colonia Tea Room, At the Sign of the Green Tea Pot, or the Brown Betty for their waffles fix. In the early 1920s, the fantastical Tam O’Shanter Inn of Los Angeles, then known as Montgomery’s Country Inn (pictured), offered chicken and waffles, a common dish at roadside tea rooms then. Tea room and coffee house magnate Alice Foote MacDougall attributed her successful career to the waffles she served in her Little Coffee House Grand Central Station restaurant in 1919.

Waffles were also a staple of tea rooms in the early 20th century. In places as varied as big city afternoon tea haunts and humble eateries in old New England homesteads, waffles attracted patrons. In 1917 New Yorkers could choose among the Colonia Tea Room, At the Sign of the Green Tea Pot, or the Brown Betty for their waffles fix. In the early 1920s, the fantastical Tam O’Shanter Inn of Los Angeles, then known as Montgomery’s Country Inn (pictured), offered chicken and waffles, a common dish at roadside tea rooms then. Tea room and coffee house magnate Alice Foote MacDougall attributed her successful career to the waffles she served in her Little Coffee House Grand Central Station restaurant in 1919.

As the Wells Manufacturing Company, maker of commercial waffle bakers, advertised in 1948: “Look! There’s a lot of Money in Waffles!”

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Anatomy of a restaurant family: the Downings

The Downing family of caterers and restaurateurs, Thomas and his sons George T. and Peter W., were activists in the causes of the abolition of slavery, black suffrage, and black education. They assisted Afro-Americans fleeing slavery before Emancipation as well as those escaping terrorism in the South in the post-Civil War period. Like many free blacks living in cities, they took up the catering trade. Similar to undertaking and barbering, catering was a personal service occupation which offered a degree of opportunity for enterprising people of color.

The Downing family of caterers and restaurateurs, Thomas and his sons George T. and Peter W., were activists in the causes of the abolition of slavery, black suffrage, and black education. They assisted Afro-Americans fleeing slavery before Emancipation as well as those escaping terrorism in the South in the post-Civil War period. Like many free blacks living in cities, they took up the catering trade. Similar to undertaking and barbering, catering was a personal service occupation which offered a degree of opportunity for enterprising people of color.

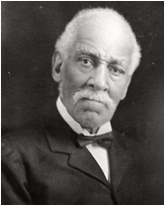

Thomas Downing (pictured), the son of freed slaves from Virginia, specialized in oysters. He opened an oyster cellar on Broad Street in New York City in the 1820s, gradually expanding it and earning a fine reputation. Often oyster cellars were “dives” but his was considered first class. He won awards for his pickled oysters which, along with his boned and jellied turkeys, were especially popular at Christmas (see 1856 ad). Over time he owned the Broad Street place and at least one other in NYC and, according to a Rhode Island directory, another in Providence. However, the press seemed always to confuse the various Downings, so it’s possible the latter was under the direction of a son.

Thomas Downing (pictured), the son of freed slaves from Virginia, specialized in oysters. He opened an oyster cellar on Broad Street in New York City in the 1820s, gradually expanding it and earning a fine reputation. Often oyster cellars were “dives” but his was considered first class. He won awards for his pickled oysters which, along with his boned and jellied turkeys, were especially popular at Christmas (see 1856 ad). Over time he owned the Broad Street place and at least one other in NYC and, according to a Rhode Island directory, another in Providence. However, the press seemed always to confuse the various Downings, so it’s possible the latter was under the direction of a son.

Because of the fame of Thomas’s oysters, his wealth (when he died in 1866, his estate was believed to be worth $100,000 – over $1,670,000 today), and his efforts to end slavery, Thomas was regarded as a patriarch of NYC’s black community. When he was ordered off a trolley car in 1855 because of his race, people in the street recognized him and pushed the stopped car forward until the conductor permitted him to continue his ride.

Thomas’s place on Broad was patronized by men in political and financial circles and he was rumored to have influential connections. Both his sons, George and Peter, had enough pull to win concessions for restaurants in government buildings. Peter ran an eating place in the Customs House in NYC, while George, a friend of MA Senator Charles Sumner, managed one in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. George (pictured) was also well known as the proprietor of a resort hotel, the Sea Girt House, in Newport, Rhode Island.

Thomas’s place on Broad was patronized by men in political and financial circles and he was rumored to have influential connections. Both his sons, George and Peter, had enough pull to win concessions for restaurants in government buildings. Peter ran an eating place in the Customs House in NYC, while George, a friend of MA Senator Charles Sumner, managed one in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. George (pictured) was also well known as the proprietor of a resort hotel, the Sea Girt House, in Newport, Rhode Island.

Thomas saw to it that his children were well educated. But neither this nor their accomplishments saved them from racial abuse. George was an eloquent writer who often confronted racism in his writings. When he lost his concession in the House restaurant in 1869 he wrote a letter to a newspaper asserting that he had been rejected because he defied the rule against serving black customers in the same dining room with whites. Nor did the family’s achievements prevent Peter’s son, Henry F. Downing, a newspaper editor, playwright, and former consul to Loanda, from being refused service in a New York restaurant in 1895.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Filed under proprietors & careers, racism

Taste of a decade: 1950s restaurants

By the end of the decade almost 40% of Americans live in suburbs and 75% have televisions. Church-going enjoys a revival. “Under God” is added to the Pledge of Allegiance and “In God we trust” is stamped on coins. Even as social pressures push women toward homemaking, 40% work outside the home. Congress passes the Internal Security Act requiring communists to register with the Attorney General. In Brown vs. Board of Education the Supreme Court rules that “separate but equal” education must end. Casual dining prevails, both at home and in public, yet interest in new dining experiences, luxury, and exotic cuisines is apparent. The restaurant industry looks forward to a bright future.

By the end of the decade almost 40% of Americans live in suburbs and 75% have televisions. Church-going enjoys a revival. “Under God” is added to the Pledge of Allegiance and “In God we trust” is stamped on coins. Even as social pressures push women toward homemaking, 40% work outside the home. Congress passes the Internal Security Act requiring communists to register with the Attorney General. In Brown vs. Board of Education the Supreme Court rules that “separate but equal” education must end. Casual dining prevails, both at home and in public, yet interest in new dining experiences, luxury, and exotic cuisines is apparent. The restaurant industry looks forward to a bright future.

Highlights

1950 Trade magazine Restaurant Management warns restaurateurs to have nothing to do with subversive organizations on the Attorney General’s list, including the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, the Hawaii Civil Liberties Committee, and the Michigan School of Social Science. – The National Restaurant Association adopts the slogan “It’s fun to eat out” to boost the family trade which has fallen off because, the organization believes, people are home watching TV.

1952 A Chicago restaurant advertises its “atomic menu,” with items such as “Guided Mussels.” – Teens get behind the wheel and drive-ins flourish. In Stockton CA patrons can choose among Billy’s Drive-In, Dick’s Drive In, Don’s Drive-In, Travo-Burger Drive Inn, or the Snow White Drive Inn. – A prominent black Denver physician wins a suit against a drive-in restaurant in Fort Morgan CO after he and his wife are refused service.

1952 A Chicago restaurant advertises its “atomic menu,” with items such as “Guided Mussels.” – Teens get behind the wheel and drive-ins flourish. In Stockton CA patrons can choose among Billy’s Drive-In, Dick’s Drive In, Don’s Drive-In, Travo-Burger Drive Inn, or the Snow White Drive Inn. – A prominent black Denver physician wins a suit against a drive-in restaurant in Fort Morgan CO after he and his wife are refused service.

1953 Dazzled and bewildered, vacationing Eleanor writes to Clare in Haverhill MA about the smorgasbord she enjoyed at Old Scandia in Miami: “Had dinner here today. Couldn’t tell you half of what I ate as the food is so different. What a life.”

1954 A wine expert advises restaurateurs that California wines, though inexpensive, are hard to merchandise because of their “strange un-American names” such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, and Chardonnay. – Restaurant surveys in Chicago reveal that “some establishments use 25 per cent fewer man hours in the kitchen now than five years ago because of pre-fabricated meats, frozen foods, pre-pared potatoes, and commercial pies and cakes.”

1955 A pancake boom begins after the Aunt Jemima Pancake House opens in the new Disneyland in Anaheim CA. – Duncan Hines says that some of the best restaurant dishes he’s ever eaten are almond souffle at Voisin in NYC, cheesecake at Lindy’s, and apple pie at the Forum Cafeterias in Chicago.

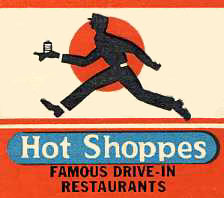

1957 The Hot Shoppes company operates restaurants and cafeterias in 11 states and D.C. as well as serving meals on airlines, the NY Thruway, and in government dining facilities. It keeps a 3,000-acre sheep and cattle ranch in Virginia, as well as a commissary, butcher shop, bakery, and ice cream plant in D.C. – In NYC the Forum of the Twelve Caesars opens. Unfazed by its campy decor and toga-clad waiters, NYT reviewer Craig Claiborne hails its “lusty elegance,” “opulent” food, and “superb” service.

1957 The Hot Shoppes company operates restaurants and cafeterias in 11 states and D.C. as well as serving meals on airlines, the NY Thruway, and in government dining facilities. It keeps a 3,000-acre sheep and cattle ranch in Virginia, as well as a commissary, butcher shop, bakery, and ice cream plant in D.C. – In NYC the Forum of the Twelve Caesars opens. Unfazed by its campy decor and toga-clad waiters, NYT reviewer Craig Claiborne hails its “lusty elegance,” “opulent” food, and “superb” service.

1958 When the IRS cracks down on expense accounts by requiring detailed proof of expenses, membership in The Diners’ Club rises sharply. In NYC, advertising executives make up the largest category of members, followed by people in the TV industry. – The Burger Chef chain gets its start.

1958 When the IRS cracks down on expense accounts by requiring detailed proof of expenses, membership in The Diners’ Club rises sharply. In NYC, advertising executives make up the largest category of members, followed by people in the TV industry. – The Burger Chef chain gets its start.

1959 Along suburban roadways national hamburger chains offer stiff competition to drive-ins and downtown hamburger shops such as Little Tavern and White Tower. With more than 100 units across the US, Ray Kroc attributes McDonalds’ success to cheap mass-produced food and the elimination of carhops. – Citizens protest that the new coffeehouse phenomenon will attract beatniks. In D.C., Coffee ‘n’ Confusion, offering Irish stew, coffee, and chess, promises to price coffee high enough to keep out undesirables.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Read about other decades: 1800 to 1810; 1810 to 1820; 1820 to 1830; 1860 to 1870; 1890 to 1900; 1900 to 1910; 1920 to 1930; 1930 to 1940; 1940 to 1950; 1960 to 1970; 1970 to 1980

Filed under miscellaneous

Basic fare: pizza

For decades pizza was seen as a light snack rather than a meal, much as it had been on the streets of Naples for centuries. An English visitor to Naples in 1843 noticed small bakeshops where “a constant hissing and thick smoke indicated the preparation of pizze, (composed of flour, lard, eggs, and garlick) and muzzarella.” In 19th-century Italy, as now, there were a variety of toppings: grated Swiss cheese, olive oil, tomatoes, and anchovies or other fish. Southern Italians brought the dish to America, and in 1903 a New York newspaper took note of a dish known as “pomidore pizza” or “tomato pie” sometimes topped with salami.

For decades pizza was seen as a light snack rather than a meal, much as it had been on the streets of Naples for centuries. An English visitor to Naples in 1843 noticed small bakeshops where “a constant hissing and thick smoke indicated the preparation of pizze, (composed of flour, lard, eggs, and garlick) and muzzarella.” In 19th-century Italy, as now, there were a variety of toppings: grated Swiss cheese, olive oil, tomatoes, and anchovies or other fish. Southern Italians brought the dish to America, and in 1903 a New York newspaper took note of a dish known as “pomidore pizza” or “tomato pie” sometimes topped with salami.

By 1905 there were a number of shops selling pizza in Italian neighborhoods of New York City, one on Spring Street (probably this was run by Gennaro Lombardi), the other on Grand. Evidently there were others but, according to an early pizza connoisseur, their pizzas were inferior “Americanized substitutes.” Although Lombardi is often cited as America’s first pizza maker it seems most likely that pizza shops existed earlier, probably beginning in the 1880s when numbers of Southern Italians began coming to this country.

Early pizza places were rarely frequented by non-Italians, and outside that community few Americans had heard of pizza before WWII. A few pizzerias here and there caught the attention of columnists and guidebook writers in the 1930s and early 1940s, such as Tom Granato’s Pizzeria Napolitana in Chicago, Lupo’s in San Francisco, and Salvatore “Sally” Consiglio’s in New Haven CT. In 1943 Ike Sewell and Ric Riccardo put aside their idea of starting a Mexican restaurant in Chicago and instead opened Pizzeria Riccardo on the corner of Ohio and Wabash. After launching a second place, they rechristened the original as “Pizzeria Uno.”

Boosted by prosperity, casual suburban lifestyles, and burgeoning youth culture after the Second World War, pizza leaped into popularity. But it was not known well everywhere. For instance, in 1948 a Corpus Christi TX restaurant review referred to the “unusual” item as “pietza pie.” It was much better known in Chicago. In 1953 there were already more than 100 pizza parlors there.

Boosted by prosperity, casual suburban lifestyles, and burgeoning youth culture after the Second World War, pizza leaped into popularity. But it was not known well everywhere. For instance, in 1948 a Corpus Christi TX restaurant review referred to the “unusual” item as “pietza pie.” It was much better known in Chicago. In 1953 there were already more than 100 pizza parlors there.

By 1956 pizza had outstripped the hot dog in popularity. But that was only the start. Pre-made crusts and frozen pizzas were coming on the market in the mid-1950s, ready to spread pizza parlors to areas of the country where few Italian-Americans had ever set foot. Increasingly, many operators of pizza parlors were not of Italian ethnicity, including the founders of the big chains such as Pizza Hut, Shakey’s, and Domino’s, all of which got their start around this time.

In the last 30 years pizza began to turn into a major cheese-delivery vehicle. Largely because of pizza, annual cheese consumption more than doubled from just over 8 pounds per person in 1960 to over 17 pounds in 1978. By 1981 most mozzarella cheese produced in the US – more than 600 million pounds a year – was for the pizza industry. Today on average we each eat somewhat more than 30 pounds of cheese a year, mozzarella is #1, and pizza has surpassed hamburgers in popularity.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Filed under food

Building a tea room empire

Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms.

Historically, few tea rooms have enjoyed financial success. So, while “empire” may be a bit grandiose, it’s hard not be impressed by the tea rooms enterprise Ida Frese and her cousin, Ada Mae Luckey, built in New York City in the early 20th century. Ida and Ada, both from a small town near Toledo OH, struck it rich by winning the patronage of wealthy society women. Over time they owned six eating places: the Colonia Tea Room (their first), the 5th Avenue Tea Room, the Garden Tea Room in the O’Neill-Adams dry goods store, the Woman’s Lunch Club, and two Vanity Fair Tea Rooms.

How they did it is a mystery not fully explained by the reputed deliciousness of their waffles nor the coziness of the Vanity Fair’s fireplace. I have not been able to find anything about their backgrounds that explains what prepared them for business success. Although contemporary publications cited them as the founders of one of NYC’s first tea rooms, it’s not clear exactly when they got their start. In 1900 Ida, 28 years old, was still living with her family in Ohio, however only ten years later she and Ada were well established in New York, running at least four tea rooms.

Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests.

Clearly they valued a good location. The Vanity Fair at 4 West Fortieth Street began in 1911, bearing a notice on its postcard (pictured) that it was across the street from the “new” public library which also opened in 1911. The tea room’s upstairs ballroom was the site of many a party, such as a Shrove Tuesday celebration in February 1914 attended by 150 masked guests.

Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.”

Adding to their financial success were several real estate coups. In 1914 Ida somehow obtained a lease on a coveted Fifth Avenue property. Her feat astonished everyone who followed real estate deals since the owner, a granddaughter of William H. Vanderbilt, had turned down repeated offers from would-be lessees and buyers. The house at #379 was one of the last residences on Fifth Avenue between 34th and 42nd streets which had not been turned into a store or office building. Ida and Ada moved the Colonia, previously on 33rd Street, to this address and rented the remaining space to retail businesses, dubbing the structure the “Women’s Commercial Building.”

In 1920 they constructed a building at 3 East 38th Street, planning to relocate the Vanity Fair Tea Room because they feared – incorrectly as it turned out – that they would lose the lease for the old Vanity Fair on West 40th. Just four years later Ida took an 84-year lease on the five-story office building at the southeast corner of Madison Avenue and 33rd Street. Eventually she bought this, as well as the Fifth Avenue property which was at some point replaced by a 6-story building. By 1926, in addition to the three pieces of Manhattan real estate, Ida and Ada had also acquired a farm in Connecticut where they grew vegetables and flowers for the tea rooms.

I don’t know the eventual fate of the tea rooms, but Ida and Ada, both in their late 80s, died in Los Angeles in 1959.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Filed under proprietors & careers, tea shops, women

A black man walked into a restaurant and …

was ignored completely. Or was asked to leave. Or no one took his order. Or was offered a seat in the kitchen. Or his food never arrived. Or it had been adulterated. Or his check was tripled.

was ignored completely. Or was asked to leave. Or no one took his order. Or was offered a seat in the kitchen. Or his food never arrived. Or it had been adulterated. Or his check was tripled.

Today in his inaugural address, President Barack Obama suggested his father might not have been served in a Washington restaurant 60 years ago. Beginning in 1949, here are examples of what happened to many dark skinned men and women who put hospitality to the test in various parts of the country.

1949 A citizens’ civil rights group in Washington D.C. visits 99 restaurants in the district and finds that 63 will not serve black customers. Upon subsequent visits, 8 establishments which had previously refused service reverse their policy, however 28 which had accepted black guests on the first visit also reverse theirs.

1949 After being snowbound on a train and then traveling for hours by bus to Spokane to keep a concert engagement, black pianist Hazel Scott, wife of congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., stops in Pasco WA and is refused service in a restaurant.

1955 India’s ambassador to the U.S. is asked to leave the public dining area of the Horizon House restaurant in Houston’s airport. He and his party are served in a private room. Texas laws forbade serving blacks and whites in the same room, however the airport was under Federal jurisdiction and not allowed to discriminate.

1956 A white county health director is fired by county commissioners for having lunch with a black nurse in a restaurant in Madison, Florida. The two women met to discuss a class for midwives.

1959 A Nigerian labor official on a U.S. tour with other international labor leaders is allowed to pass through the line at the Forum Cafeteria in downtown Kansas City, but later, after hearing complaints from white patrons, the cafeteria manager orders him never to return.

1960 Members of the National Council of Jewish Women visit 200 Tucson restaurants urging them to end racial discrimination. Seventy restaurants flatly refuse to comply.

1961 Numbers of diplomats from newly independent African nations are refused service in restaurants on Route 40 in Maryland, including the Ambassador to Chad who is on his way to the White House to present his papers to President Kennedy. The State Department takes action to protect the diplomats from discrimination while leaving black American citizens to fend for themselves. To expose the double standard, three reporters from a black Baltimore newspaper dress in African robes and are well received in Maryland restaurants notorious for their racist policies.

1962 Conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein walks out of Miller Brothers restaurant in Baltimore after he is told that a recently hired NY Philharmonic violinist in his party, who is black, cannot be served.

1964 Following passage of the Civil Rights Act, Lester Maddox closes his Pickrick restaurant in Atlanta rather than serve blacks. He claims that communists are behind FBI enforcement of civil rights laws.

1964 The Emporia Diner in Virginia admits to having two menus (and that the higher priced one is used “at any time it is felt that business may be adversely affected”) after a black Baltimore woman brings suit saying her family was charged more than three times what whites paid for the same meal.

1964 The Emporia Diner in Virginia admits to having two menus (and that the higher priced one is used “at any time it is felt that business may be adversely affected”) after a black Baltimore woman brings suit saying her family was charged more than three times what whites paid for the same meal.

1965 Comedian Dick Gregory and a group of blacks testing accommodation at local restaurants are turned away by a steakhouse in Tuscaloosa AL after the owner shows them a list of about 1,000 names of people allegedly holding reservations.

1970 According to a complaint brought by the U.S. Attorney General’s office, Ayers Log Cabin Pit Cooked Bar-B-Que, a restaurant near Washington, North Carolina, displays a sign indicating that any money spent there by black patrons will be donated to the Ku Klux Klan.

1993 Although racial discrimination in restaurants diminishes in the 1970s and 1980s, a slew of complaints against the Denny’s chain demonstrates that problems persist. In May six black Secret Service agents file a federal suit charging that their table was not served breakfast in a Denny’s in Annapolis MD while all 15 white agents received their meals.

Read about how both black and white Americans fought discrimination in restaurants.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Filed under racism

Who hasn’t heard of Maxim’s in Paris?

The name has cast a spell over Americans since the 1890s and bits of its odd history have played out in the U.S. The fortunes of the “world’s most famous restaurant” have risen and fallen. It has won high ratings and lost them. It has been the subject and site of operettas, songs, and movies. It has been declared a French national treasure and an altar to haute cuisine, but also a fraud and a tourist trap. Maxim’s name has appeared on perfumes, airplane meals, and franchised outlets, yet even today it resonates.

The name has cast a spell over Americans since the 1890s and bits of its odd history have played out in the U.S. The fortunes of the “world’s most famous restaurant” have risen and fallen. It has won high ratings and lost them. It has been the subject and site of operettas, songs, and movies. It has been declared a French national treasure and an altar to haute cuisine, but also a fraud and a tourist trap. Maxim’s name has appeared on perfumes, airplane meals, and franchised outlets, yet even today it resonates.

According to most accounts a waiter named Maxime Gaillard began Maxim’s in 1893. Yet another report calls him maitre d’hôtel Signor Maximo, while another stakes a claim for Georges Everard as founder in 1890. Everyone seems to agree, though, that the early Maxim’s was a late-night glamour magnet for American and English visitors to Paris, liberally supplied with friendly prostitutes. In 1899 it acquired a flamboyant Art Nouveau interior with enough murals, curves, and mirrors for a loopy carnival ride. Its prices were high, which may explain why many turn-of-the-century patrons, though dressed in silks and tuxedos, preferred to watch the action while munching pommes frites, an early specialty of the house.

According to most accounts a waiter named Maxime Gaillard began Maxim’s in 1893. Yet another report calls him maitre d’hôtel Signor Maximo, while another stakes a claim for Georges Everard as founder in 1890. Everyone seems to agree, though, that the early Maxim’s was a late-night glamour magnet for American and English visitors to Paris, liberally supplied with friendly prostitutes. In 1899 it acquired a flamboyant Art Nouveau interior with enough murals, curves, and mirrors for a loopy carnival ride. Its prices were high, which may explain why many turn-of-the-century patrons, though dressed in silks and tuxedos, preferred to watch the action while munching pommes frites, an early specialty of the house.

Detractors, such as H. L. Mencken, charged that Maxim’s “gypsy” orchestra was composed of Germans and that the toy balloons floating around were from “the Elite Novelty Co. of Jersey City, U.S.A.” In “Paris à la Carte” (1911), Julian Street, an authority on French food and wines, asserted “I abominate it,” and denounced it as “a brazen fake, over-advertised, ogling, odoriferous; a nightmare of smoke, champagne, and banality.” Debauched merrymakers aside, these were the golden years, before World War I, the era of wine, women, and song on which the Maxim’s legend would be built.

Detractors, such as H. L. Mencken, charged that Maxim’s “gypsy” orchestra was composed of Germans and that the toy balloons floating around were from “the Elite Novelty Co. of Jersey City, U.S.A.” In “Paris à la Carte” (1911), Julian Street, an authority on French food and wines, asserted “I abominate it,” and denounced it as “a brazen fake, over-advertised, ogling, odoriferous; a nightmare of smoke, champagne, and banality.” Debauched merrymakers aside, these were the golden years, before World War I, the era of wine, women, and song on which the Maxim’s legend would be built.

Business was slowed down by war and evidently did not pick up much in the 1920s. By the 1930s Maxim’s was ready for an overhaul. Octave Vaudable acquired it in 1932 (however in other accounts the owner was a British syndicate). After undergoing German WWII occupation followed by service as a British officers’ mess hall, the restaurant resumed regular operation in 1946 under the management of Octave’s son and daughter-in-law. The reopening, according to Colman Andrews (wine and food writer and co-founder of Saveur), “marked the end of the legendary Maxim’s and the beginning of the Maxim’s legend.”

By 1953 the restaurant had earned 3 stars in the Michelin Guide and was starting on a new course. It had developed a frozen food division which supplied airplane meals and was poised to sell frozen sauces and entrées in select American stores. In another twist, Maxim’s authorized a Chicago franchise which in 1963 opened an exact replica of the original with chefs trained in Paris. In the 1970s Maxim’s began a downward slide in the Kleber and Gault/Millau guidebooks. By 1978 the restaurant was no longer listed in Michelin, but more franchises were popping up in Tokyo, Mexico City, New York, and Palm Springs. About this time, fashion designer Pierre Cardin, who would buy Maxim’s in 1981, obtained a license and began to merchandise candy, perfume, men’s wear, and other goods under that label. Several Maxim’s have come and gone around the world but today the original Paris Maxim’s persists and there are Maxim’s luxury restaurants and hotels in 7 other cities.

By 1953 the restaurant had earned 3 stars in the Michelin Guide and was starting on a new course. It had developed a frozen food division which supplied airplane meals and was poised to sell frozen sauces and entrées in select American stores. In another twist, Maxim’s authorized a Chicago franchise which in 1963 opened an exact replica of the original with chefs trained in Paris. In the 1970s Maxim’s began a downward slide in the Kleber and Gault/Millau guidebooks. By 1978 the restaurant was no longer listed in Michelin, but more franchises were popping up in Tokyo, Mexico City, New York, and Palm Springs. About this time, fashion designer Pierre Cardin, who would buy Maxim’s in 1981, obtained a license and began to merchandise candy, perfume, men’s wear, and other goods under that label. Several Maxim’s have come and gone around the world but today the original Paris Maxim’s persists and there are Maxim’s luxury restaurants and hotels in 7 other cities.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

Filed under elite restaurants

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.