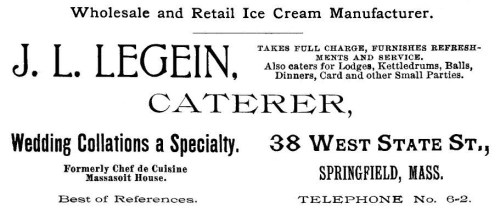

“Become a chef and see the world!” might have been the motto of many of the chefs who came to the United States from Europe in the 19th century. Take Joseph L. Legein, born in Belgium in 1852. He compressed a lot of traveling into his young working life. His biography could be used as a recipe for a colorful culinary career. Did he ever imagine he would end up as an ice cream maker in Springfield, Massachusetts?

“Become a chef and see the world!” might have been the motto of many of the chefs who came to the United States from Europe in the 19th century. Take Joseph L. Legein, born in Belgium in 1852. He compressed a lot of traveling into his young working life. His biography could be used as a recipe for a colorful culinary career. Did he ever imagine he would end up as an ice cream maker in Springfield, Massachusetts?

To duplicate Joseph’s career, follow these directions carefully:

When you are 14 apprentice with the famous Paris caterers Potel & Chabot, the largest firm in Europe in the late 1860s. (They are still in business today.)

After earning a diploma two years later, secure posts at Paris restaurants such as the celebrated Café Anglais.

Then, take positions in the households of rich and powerful men such as Baron Rothschild and Louis Faidherbe, the latter a general recalled from Senegal in 1870 to battle the Prussians who are advancing on Paris.

Every chance you get, travel throughout Europe visiting international exhibitions where pièces-montées made by chefs of spun sugar, gum and almond paste are displayed. You will need to make these for centerpieces at formal dinners.

Every chance you get, travel throughout Europe visiting international exhibitions where pièces-montées made by chefs of spun sugar, gum and almond paste are displayed. You will need to make these for centerpieces at formal dinners.

Go to Brussels and work in the Café Riche as night chef.

Next, take a position in the Hotel de Suède in Brussels and get chummy with Alexander, chef to the Belgian royal court, who gets you a gig working with him.

At 20 you are ready to take charge of a banquet staff of seven at the Hotel de la Paix in Antwerp, a highlight of which will be overseeing a 12-course dinner for 1,400 guests.

Go to London to run a kitchen in one of the Inns of Court (but do not get sick after 7 months and return to work at the Hotel de la Paix).

On the spur of the moment decide to sail for America to attend the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. You are about to take up residence in your 4th country and your 8th major city.

Immediately upon landing, accept a position as chef at the restaurant connected with the Globe Hotel, one of the huge hotels thrown up overnight to house Centennial visitors which will be demolished as soon as the fair ends.

After a few months, quit this job to become chef at the Palmer House in Chicago.

Leave this a couple of months later and take a job opening the new Ogden House at Council Bluffs, Iowa. (Why would you leave the Palmer House for this?)

Decide you aren’t paid enough. Go to New York and sign on at the new Windsor Hotel.

While at the Windsor accept a job as chef at the Massasoit House, the top hotel in Springfield MA. You are now 25 years old and this is your 14th or 15th job. Maybe you should stick at it for a while.

Stay at the Massasoit House until you are 34, in 1886, then open your own catering company specializing in ice cream manufacturing.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

What a pain the rich can be. That’s the message you’ll take away if perchance you pick up The Colony Cookbook by Gene Cavallero Jr. and Ted James, published in 1972. The dedication page is plaintively inscribed by Gene, “To my father and all suffering restaurateurs.” Chapter 3 details what caused the suffering, namely the privileged customers who imposed upon him and his father in so many ways. They

What a pain the rich can be. That’s the message you’ll take away if perchance you pick up The Colony Cookbook by Gene Cavallero Jr. and Ted James, published in 1972. The dedication page is plaintively inscribed by Gene, “To my father and all suffering restaurateurs.” Chapter 3 details what caused the suffering, namely the privileged customers who imposed upon him and his father in so many ways. They

The London Chop House, Detroit’s 21 Club, enjoyed a ranking as one of the country’s top restaurants in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. James Beard named it as one of the ten best restaurants nationwide in 1961, the same year it won a Darnell Survey award as one of America’s Favorites. It won Holiday magazine awards repeatedly. Honors continued throughout the 1970s, and in 1980 it made Playboy’s top 25 list.

The London Chop House, Detroit’s 21 Club, enjoyed a ranking as one of the country’s top restaurants in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. James Beard named it as one of the ten best restaurants nationwide in 1961, the same year it won a Darnell Survey award as one of America’s Favorites. It won Holiday magazine awards repeatedly. Honors continued throughout the 1970s, and in 1980 it made Playboy’s top 25 list.

The Grubers were adept at flattering the male ego. When a guest made a reservation, he would arrive to find his table with books of matches and a reserved sign all imprinted with his name, as well as a card with a coin in a slot reimbursing him for his phone call. Alpha types jostled for table #1, while regulars glowed with the knowledge that their suavely jacketed waiter had remembered how many ice cubes they liked in their highballs. To keep up with escalating demand, in 1952 the Grubers opened a second place across the street, the Caucus Club. The 1980s turned out to be a tough decade for the Chop House. Les Gruber sold it in 1982, chef Schmidt left, and the new owner passed away. Despite efforts to keep it afloat, it closed in 1991.

The Grubers were adept at flattering the male ego. When a guest made a reservation, he would arrive to find his table with books of matches and a reserved sign all imprinted with his name, as well as a card with a coin in a slot reimbursing him for his phone call. Alpha types jostled for table #1, while regulars glowed with the knowledge that their suavely jacketed waiter had remembered how many ice cubes they liked in their highballs. To keep up with escalating demand, in 1952 the Grubers opened a second place across the street, the Caucus Club. The 1980s turned out to be a tough decade for the Chop House. Les Gruber sold it in 1982, chef Schmidt left, and the new owner passed away. Despite efforts to keep it afloat, it closed in 1991.

When we get into questions of the origins of certain dishes we have left history behind and entered into the murky depths of lore and legend.

When we get into questions of the origins of certain dishes we have left history behind and entered into the murky depths of lore and legend. A strong inventorship claim was presented by Caesar’s brother, Alexander, in the 1960s. Caesar died in 1956, while running a grocery store in Los Angeles where he produced and bottled Caesar salad dressing. According to Alexander’s son, who ran Cardini’s in Mexico City, the two brothers had developed the salad together in a Tijuana restaurant in their younger days, improvising on a recipe their mother used when they were boys in Italy. In this “Mother’s recipe” account, the salad was initially called “Aviator’s salad” in honor of their customers who were soldiers, sailors, and airmen.

A strong inventorship claim was presented by Caesar’s brother, Alexander, in the 1960s. Caesar died in 1956, while running a grocery store in Los Angeles where he produced and bottled Caesar salad dressing. According to Alexander’s son, who ran Cardini’s in Mexico City, the two brothers had developed the salad together in a Tijuana restaurant in their younger days, improvising on a recipe their mother used when they were boys in Italy. In this “Mother’s recipe” account, the salad was initially called “Aviator’s salad” in honor of their customers who were soldiers, sailors, and airmen. In the 1850s the great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of New York’s Central Park, traveled through the South to investigate the institution of slavery. His observations were published in three volumes which were influential in turning readers against slavery. Around 1857 he traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, where he stayed at the Commercial Hotel. Although it was considered a first-class establishment, things did not go well for Frederick in the dining room as his journal entry for March 20, below, reveals. Among the dishes appearing on the not-too-elegant menu were “Beef heart egg sauce,” “Calf feet mushroom sauce,” “Bear sausages,” “Fried cabbage,” and, for dessert, “Sliced potatoe pie.” Better than whole potato pie, I guess.

In the 1850s the great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of New York’s Central Park, traveled through the South to investigate the institution of slavery. His observations were published in three volumes which were influential in turning readers against slavery. Around 1857 he traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, where he stayed at the Commercial Hotel. Although it was considered a first-class establishment, things did not go well for Frederick in the dining room as his journal entry for March 20, below, reveals. Among the dishes appearing on the not-too-elegant menu were “Beef heart egg sauce,” “Calf feet mushroom sauce,” “Bear sausages,” “Fried cabbage,” and, for dessert, “Sliced potatoe pie.” Better than whole potato pie, I guess. People have strong feelings about their favorite dishes from restaurant chains. I am thankful to all those who poured their hearts out on the subject on Jane & Michael Stern’s ever-fascinating Roadfood forums. I have excerpted the following wistful memories from “Long-gone regional franchises” which took on a life of its own and ran for years. After each snippet is the pertinent chain restaurant.

People have strong feelings about their favorite dishes from restaurant chains. I am thankful to all those who poured their hearts out on the subject on Jane & Michael Stern’s ever-fascinating Roadfood forums. I have excerpted the following wistful memories from “Long-gone regional franchises” which took on a life of its own and ran for years. After each snippet is the pertinent chain restaurant. — The Cheese Frenchies were unique. [King’s Food Host]

— The Cheese Frenchies were unique. [King’s Food Host] — Pickles, diced onion, relish, mustard, ketchup and mayo were all available. [25 Cent Hamburger]

— Pickles, diced onion, relish, mustard, ketchup and mayo were all available. [25 Cent Hamburger] Who was first to realize that they could cover bad plaster on their ceilings and walls with canvas and call their restaurant a covered wagon or a chuck wagon? The idea seems to have struck initially in the 1930s, at least that’s when the first Covered Wagon restaurant I’ve found dates from. It was in the Old West – no, make that Minneapolis, with a second in St. Paul. Red checkered tablecloths covered the tables and in the 195os the female waitstaff wore long calico dresses with aprons, a fact I know thanks to the well-illustrated book Minnesota Eats Out. There was also a Covered Wagon in Chicago in the 1940s, presumably under different ownership but with the same tablecloths.

Who was first to realize that they could cover bad plaster on their ceilings and walls with canvas and call their restaurant a covered wagon or a chuck wagon? The idea seems to have struck initially in the 1930s, at least that’s when the first Covered Wagon restaurant I’ve found dates from. It was in the Old West – no, make that Minneapolis, with a second in St. Paul. Red checkered tablecloths covered the tables and in the 195os the female waitstaff wore long calico dresses with aprons, a fact I know thanks to the well-illustrated book Minnesota Eats Out. There was also a Covered Wagon in Chicago in the 1940s, presumably under different ownership but with the same tablecloths. The wagon-esque theme caught on big during the 1950s, inspired partly by TV westerns and partly by the fame of Las Vegas chuck wagon buffets which provided grub for gamblers from midnight ‘til dawn. If not for Vegas envy, why else would there have been one in Miami Beach in 1955? Apparently seeing no local cuisine worth merchandising, restaurateurs there chose from a grab bag of themes such as Smorgs, Polynesian, and Ken’s Pancake Parade. (“Grandma’s Kitchen” was the town’s most venerable eating establishment at the time.)

The wagon-esque theme caught on big during the 1950s, inspired partly by TV westerns and partly by the fame of Las Vegas chuck wagon buffets which provided grub for gamblers from midnight ‘til dawn. If not for Vegas envy, why else would there have been one in Miami Beach in 1955? Apparently seeing no local cuisine worth merchandising, restaurateurs there chose from a grab bag of themes such as Smorgs, Polynesian, and Ken’s Pancake Parade. (“Grandma’s Kitchen” was the town’s most venerable eating establishment at the time.) Around 1960 a Potsdam NY man got the idea of franchising

Around 1960 a Potsdam NY man got the idea of franchising  During the war (1941-1945) the creation of 17 million new jobs finally pulls the economy out of the Depression. Millions of married women enter the labor force. The demand for restaurant meals escalates, increasing from a pre-war level of 20 million meals served per day to over 60 million. The combination of increased restaurant patronage with labor shortages, government-ordered price freezes, and rationing of basic foods puts restaurants in a squeeze. With gasoline rationing, many roadside cafes and hamburger stands close.

During the war (1941-1945) the creation of 17 million new jobs finally pulls the economy out of the Depression. Millions of married women enter the labor force. The demand for restaurant meals escalates, increasing from a pre-war level of 20 million meals served per day to over 60 million. The combination of increased restaurant patronage with labor shortages, government-ordered price freezes, and rationing of basic foods puts restaurants in a squeeze. With gasoline rationing, many roadside cafes and hamburger stands close. 1941 When the restaurant in the French pavilion at the New York World’s Fair closes, its head Henri Soulé decides he will not return to a Paris occupied by Germans. He and ten waiters remain in New York and open Le Pavillon. Columnist Lucius Beebe declares its cuisine “absolutely faultless,” with prices “of positively Cartier proportions.” – Chicago cafeteria operator

1941 When the restaurant in the French pavilion at the New York World’s Fair closes, its head Henri Soulé decides he will not return to a Paris occupied by Germans. He and ten waiters remain in New York and open Le Pavillon. Columnist Lucius Beebe declares its cuisine “absolutely faultless,” with prices “of positively Cartier proportions.” – Chicago cafeteria operator  1946 Like health departments all across the country, NYC begins a crack down on

1946 Like health departments all across the country, NYC begins a crack down on  1949 Howard Johnson’s, the country’s largest restaurant chain, reports a record volume of business for the year. HoJos, which has not yet spread farther west than Fort Wayne IN, plans a move into California.

1949 Howard Johnson’s, the country’s largest restaurant chain, reports a record volume of business for the year. HoJos, which has not yet spread farther west than Fort Wayne IN, plans a move into California. Not many people get as excited as I do about books of obsolete restaurant reviews. I especially like The New Orleans Underground Gourmet. In the 1973 edition reviewer Richard H. Collin zapped a few well-known tourist places as well as some less expensive restaurants which had “little or nothing to recommend them” in order to “spare the reader’s time and stomach.” He not only performed a service but produced enjoyable reading for anyone inclined to find humor in bad reviews.

Not many people get as excited as I do about books of obsolete restaurant reviews. I especially like The New Orleans Underground Gourmet. In the 1973 edition reviewer Richard H. Collin zapped a few well-known tourist places as well as some less expensive restaurants which had “little or nothing to recommend them” in order to “spare the reader’s time and stomach.” He not only performed a service but produced enjoyable reading for anyone inclined to find humor in bad reviews.

In the mid-19th century there was only one American restaurant with a worldwide reputation,

In the mid-19th century there was only one American restaurant with a worldwide reputation,  From the 1870s up to the 1930s, but not so much after that (except for New Orleans?), I’ve found Delmonicos in Los Angeles, Denver, Colorado Springs, Tombstone, Phoenix, Helena, Portland OR, El Paso, Dallas, Walla Walla, Mobile, Memphis, Winona MN, Leavenworth KS, Detroit, Key West (1931 ad pictured), Pittsburgh, Buffalo – and more. Proprietors names ranged from Gutekunst to Garibotti to McDougal.

From the 1870s up to the 1930s, but not so much after that (except for New Orleans?), I’ve found Delmonicos in Los Angeles, Denver, Colorado Springs, Tombstone, Phoenix, Helena, Portland OR, El Paso, Dallas, Walla Walla, Mobile, Memphis, Winona MN, Leavenworth KS, Detroit, Key West (1931 ad pictured), Pittsburgh, Buffalo – and more. Proprietors names ranged from Gutekunst to Garibotti to McDougal.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.