As a meal Thanksgiving dinner is steeped in agrarian values and customs that do not thrive in restaurants, which are primarily urban inventions. It is also incongruous to celebrate what has become a domestic festival in a commercial setting. Neither gourmet restaurants nor fast food eateries present the homeyness considered conducive to celebrating the holiday.

As a meal Thanksgiving dinner is steeped in agrarian values and customs that do not thrive in restaurants, which are primarily urban inventions. It is also incongruous to celebrate what has become a domestic festival in a commercial setting. Neither gourmet restaurants nor fast food eateries present the homeyness considered conducive to celebrating the holiday.

Nor is restaurant cuisine quite right for Thanksgiving. Thanksgiving dinner represents the ne plus ultra of comfort food. According to consumer researchers Melanie Wallendorf and Eric Arnould (“‘We Gather Together’: Consumption Rituals of Thanksgiving Day,” Journal of Consumer Research, June 1991), the typical dishes served are like baby food in that they are “baked, boiled, and mashed” foods which are soft in texture and prepared without much seasoning. The emphasis is on the presentation and consumption of abundance, which for participants implies almost compulsory overeating. Few people are interested in culinary innovation which, for most, threatens the essentially infantile pleasures of the occasion.

Despite restaurants’ apparent inadequacy in meeting the challenge of this American national gustatory ritual, there is some evidence that Thanksgiving restaurant-going has increased over the course of the past century. The tendency, though, is to see this more as symptom than innovation. The sentiment expressed in 1892, that Thanksgiving dinner in a restaurant is a “rather melancholy thing” has not been eradicated.

Despite restaurants’ apparent inadequacy in meeting the challenge of this American national gustatory ritual, there is some evidence that Thanksgiving restaurant-going has increased over the course of the past century. The tendency, though, is to see this more as symptom than innovation. The sentiment expressed in 1892, that Thanksgiving dinner in a restaurant is a “rather melancholy thing” has not been eradicated.

One would think that the restaurants best positioned to capture the Thanksgiving trade would be those with Early American decor, or venerable restaurants that can reference tradition, such as Brooklyn’s Gage and Tollner, or those that stress home-based values, such as tea rooms. In the Los Angeles area, which seems to have had a fair amount of Thanksgiving restaurant trade in the 1920s, diners could choose from Ye Golden Lantern Tea Room or the Green Tea Pot of Pasadena, among others. Harder to understand, though, was the appeal of restaurants serving chop suey to the strains of Hawaiian music. About the same time Indianapolis was well supplied with dining out choices for the holiday, ranging from traditional Thanksgiving fare at the Friendly Inn to barbecue at Ye Log Cabin to a “Special Turkey Tostwich, 25c” at Ryker’s. The city’s Bamboo Inn offered two styles of Thanksgiving dinner, one with turkey and the usual trimmings and the other a Mandarin Dinner with Shrimp Egg Foo Young and Turkey Chop Suey.

One would think that the restaurants best positioned to capture the Thanksgiving trade would be those with Early American decor, or venerable restaurants that can reference tradition, such as Brooklyn’s Gage and Tollner, or those that stress home-based values, such as tea rooms. In the Los Angeles area, which seems to have had a fair amount of Thanksgiving restaurant trade in the 1920s, diners could choose from Ye Golden Lantern Tea Room or the Green Tea Pot of Pasadena, among others. Harder to understand, though, was the appeal of restaurants serving chop suey to the strains of Hawaiian music. About the same time Indianapolis was well supplied with dining out choices for the holiday, ranging from traditional Thanksgiving fare at the Friendly Inn to barbecue at Ye Log Cabin to a “Special Turkey Tostwich, 25c” at Ryker’s. The city’s Bamboo Inn offered two styles of Thanksgiving dinner, one with turkey and the usual trimmings and the other a Mandarin Dinner with Shrimp Egg Foo Young and Turkey Chop Suey.

Although the president of the Saga Corporation, a restaurant supplier, insisted in 1978 that eating out on Thanksgiving and Christmas had lost its stigma, events such as turkey dinners given by churches and soup kitchens for the poor and homeless, as well as explanations given by restaurant patrons in surveys, would indicate otherwise. They seem to suggest that dining in a restaurant on Thanksgiving is frequently a compensation for some sort of lack on the homefront rather than a positive attraction in its own right. Wallenberg and Arnould reported that only 1.8% of the people they surveyed said they would prefer to spend Thanksgiving in a restaurant than at home.

© Jan Whitaker, 2009

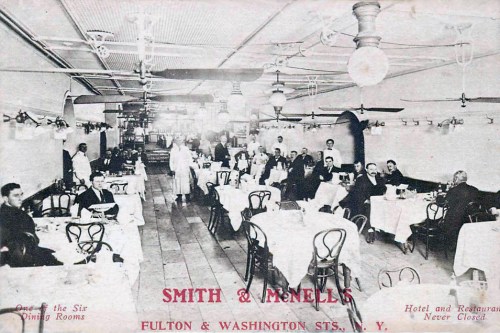

All things considered, the best restaurants that this country has produced probably have been unpretentious, inexpensive, high-volume eateries located close to sources of fresh food. In 19th-century New York City’s Smith & McNell’s, across from the booming Washington Market, was a leading example of the type. Its patronage came largely from dealers, farmers, and customers who worked and shopped at the market. Around 1891 the restaurant reportedly provided more meals than any eating place in the city, as many as 10,000 a day.

All things considered, the best restaurants that this country has produced probably have been unpretentious, inexpensive, high-volume eateries located close to sources of fresh food. In 19th-century New York City’s Smith & McNell’s, across from the booming Washington Market, was a leading example of the type. Its patronage came largely from dealers, farmers, and customers who worked and shopped at the market. Around 1891 the restaurant reportedly provided more meals than any eating place in the city, as many as 10,000 a day. There are many discrepancies in accounts of this restaurant’s history but it seems most likely it was established in the late 1840s by Thomas R. McNell and Henry Smith. McNell was an Irish immigrant, born sometime between 1825 and 1830. According to one account he and Smith had been night watchmen before taking over the coffee house run by Frederick Way on Washington Street near the market. Both McNell and Smith became wealthy and McNell acquired a lordly estate in Alpine, New Jersey, as well as a California ranch. He continued working in the business until a ripe old age and died in 1917 a few years after the restaurant (and associated hotel) closed.

There are many discrepancies in accounts of this restaurant’s history but it seems most likely it was established in the late 1840s by Thomas R. McNell and Henry Smith. McNell was an Irish immigrant, born sometime between 1825 and 1830. According to one account he and Smith had been night watchmen before taking over the coffee house run by Frederick Way on Washington Street near the market. Both McNell and Smith became wealthy and McNell acquired a lordly estate in Alpine, New Jersey, as well as a California ranch. He continued working in the business until a ripe old age and died in 1917 a few years after the restaurant (and associated hotel) closed.

According to accounts, “D. L.” wrote his own colorful advertising copy, such as, “These hams are cut from healthy young hogs grown in the sunshine on beautifully rolling Wisconsin farms where corn, barley, milk and acorns are unstintingly fed to them, producing that silken meat so rich in wonderful flavor.” Equally over the top was his copy for Idaho baked potatoes, with references to a “bulging beauty, grown in the ashes of extinct volcanoes, scrubbed and washed, then baked in a whirlwind of tempestuous fire until the shell crackles with brittleness…” Customers who had not previously eaten baked potatoes soon learned to ask for “an Idaho.” Another heavily promoted dish, “Old Fashioned Louisiana Strawberry Shortcake,” was “topped with pure, velvety whipped cream like puffs of snow.”

According to accounts, “D. L.” wrote his own colorful advertising copy, such as, “These hams are cut from healthy young hogs grown in the sunshine on beautifully rolling Wisconsin farms where corn, barley, milk and acorns are unstintingly fed to them, producing that silken meat so rich in wonderful flavor.” Equally over the top was his copy for Idaho baked potatoes, with references to a “bulging beauty, grown in the ashes of extinct volcanoes, scrubbed and washed, then baked in a whirlwind of tempestuous fire until the shell crackles with brittleness…” Customers who had not previously eaten baked potatoes soon learned to ask for “an Idaho.” Another heavily promoted dish, “Old Fashioned Louisiana Strawberry Shortcake,” was “topped with pure, velvety whipped cream like puffs of snow.” Another factor in his success was winning catering contracts at two world’s fairs, Chicago in 1933 and New York in 1939-40. Following the NY fair he outbid Louis B. Mayer for an immensely valuable piece of Times Square real estate on the corner of 43rd and Broadway. He hired Skidmore, Owings & Merrill to design a two-story, glass-fronted moderne building (pictured), outfitted with an escalator and a show-off gleaming stainless steel kitchen. The restaurant served 8,500 meals on opening day.

Another factor in his success was winning catering contracts at two world’s fairs, Chicago in 1933 and New York in 1939-40. Following the NY fair he outbid Louis B. Mayer for an immensely valuable piece of Times Square real estate on the corner of 43rd and Broadway. He hired Skidmore, Owings & Merrill to design a two-story, glass-fronted moderne building (pictured), outfitted with an escalator and a show-off gleaming stainless steel kitchen. The restaurant served 8,500 meals on opening day. I always find it difficult to judge menus from the 19th century because our eating habits, food preferences, and food resources have changed considerably since then. It is difficult to decide whether any given menu is fine, average, or poor. The following menu was designed by a hotel steward (stewards were in charge of expenses) for a banquet in 1893. Almost certainly wines would have been served with the seven courses (which are Soup, Fish, Roast, Punch, Entree, Dessert, and Coffee).

I always find it difficult to judge menus from the 19th century because our eating habits, food preferences, and food resources have changed considerably since then. It is difficult to decide whether any given menu is fine, average, or poor. The following menu was designed by a hotel steward (stewards were in charge of expenses) for a banquet in 1893. Almost certainly wines would have been served with the seven courses (which are Soup, Fish, Roast, Punch, Entree, Dessert, and Coffee). It seems as though almost all of history’s food forces have cooperated to give cheese top billing in restaurant meals today. Only one cheesy custom failed to catch on, that of finishing a meal with cheese and fruit as was done in small French and Italian restaurants in the later 19th century. Craig Claiborne argued in 1965 that even the best New York restaurants didn’t know how to handle the cheese course. They had poor selections which tended to be old, overripe, or served too cold. One restaurant admitted their chef was in the habit of popping cheese straight from the fridge into the oven to soften it. Restaurateurs that Claiborne interviewed insisted that Americans didn’t like cheese after a meal. I’d agree that most prefer their after-dinner cheese in the form of cheesecake.

It seems as though almost all of history’s food forces have cooperated to give cheese top billing in restaurant meals today. Only one cheesy custom failed to catch on, that of finishing a meal with cheese and fruit as was done in small French and Italian restaurants in the later 19th century. Craig Claiborne argued in 1965 that even the best New York restaurants didn’t know how to handle the cheese course. They had poor selections which tended to be old, overripe, or served too cold. One restaurant admitted their chef was in the habit of popping cheese straight from the fridge into the oven to soften it. Restaurateurs that Claiborne interviewed insisted that Americans didn’t like cheese after a meal. I’d agree that most prefer their after-dinner cheese in the form of cheesecake. Cheese has been a staple food in American eating places probably since the first tavern opened. Regular meals were served only at stated hours but hungry customers could get cheese and crackers at the bar whatever the hour. For “Gentlemen en’passant,” the Union Coffee House in Boston promised in 1785 that it could always furnish the basics of life: oysters, English cheese, and London Porter. Across the river in Cambridge, the renowned

Cheese has been a staple food in American eating places probably since the first tavern opened. Regular meals were served only at stated hours but hungry customers could get cheese and crackers at the bar whatever the hour. For “Gentlemen en’passant,” the Union Coffee House in Boston promised in 1785 that it could always furnish the basics of life: oysters, English cheese, and London Porter. Across the river in Cambridge, the renowned  Cheeseburgers were a product of the fast food industry of the 1920s, claimed as inventions by both the Rite Spot of Southern California and the Little Tavern of Louisville. Strange there aren’t thousands of other contenders because what was there to invent, really? Cheeseburgers were strongly associated with Southern California before WWII — Bob’s Big Boy of LA introduced cheeseburgers in 1937. Another step forward came in the 1930s when a bill was introduced in the Wisconsin legislature requiring restaurants and cafes to serve 2/3 oz. of Wisconsin cheese with every meal costing 25 cents or more. In the same decade Kraft Cheese was among major food producers providing restaurants with standardized recipe cards.

Cheeseburgers were a product of the fast food industry of the 1920s, claimed as inventions by both the Rite Spot of Southern California and the Little Tavern of Louisville. Strange there aren’t thousands of other contenders because what was there to invent, really? Cheeseburgers were strongly associated with Southern California before WWII — Bob’s Big Boy of LA introduced cheeseburgers in 1937. Another step forward came in the 1930s when a bill was introduced in the Wisconsin legislature requiring restaurants and cafes to serve 2/3 oz. of Wisconsin cheese with every meal costing 25 cents or more. In the same decade Kraft Cheese was among major food producers providing restaurants with standardized recipe cards. It was after WWII that cheese spread its melted gooeyness everywhere — on

It was after WWII that cheese spread its melted gooeyness everywhere — on  They are so clever and, yes, so corny in a circus-y way that revolving restaurants seem like they must be a product of American ingenuity – but they aren’t. The restaurant in Seattle’s 1962 World’s Fair Space Needle was not the first. Nor was it the second, third, or fourth. According to Chad Randl in A History of Buildings that Rotate, Swivel, and Pivot, the first revolving tower with a restaurant opened in 1959 in Dortmund, Germany. Sometime in 1961 came spinning restaurants in Frankfurt, Cairo, and Honolulu (pictured), in about that order.

They are so clever and, yes, so corny in a circus-y way that revolving restaurants seem like they must be a product of American ingenuity – but they aren’t. The restaurant in Seattle’s 1962 World’s Fair Space Needle was not the first. Nor was it the second, third, or fourth. According to Chad Randl in A History of Buildings that Rotate, Swivel, and Pivot, the first revolving tower with a restaurant opened in 1959 in Dortmund, Germany. Sometime in 1961 came spinning restaurants in Frankfurt, Cairo, and Honolulu (pictured), in about that order. The revolving building itself actually came earlier and was rather simple technologically. In 1898 a leading attraction in Yarmouth, a seaside resort in England, was a rotating observation tower on the beach. Decades later designer Norman Bel Geddes proposed a restaurant set atop a rotating column for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933 (pictured). Unlike his, though, the design used by most restaurants features an interior ring containing the restaurant’s kitchen that does not rotate.

The revolving building itself actually came earlier and was rather simple technologically. In 1898 a leading attraction in Yarmouth, a seaside resort in England, was a rotating observation tower on the beach. Decades later designer Norman Bel Geddes proposed a restaurant set atop a rotating column for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933 (pictured). Unlike his, though, the design used by most restaurants features an interior ring containing the restaurant’s kitchen that does not rotate. Despite being fairly easy to engineer and not really all that new, in the 1960s revolving buildings became symbols of progress. Often set atop communications towers, they were intended to help defray costs of tower construction and operation. Today, whether in towers or on hotel roofs (where they look like flying saucers that have landed), they continue to represent modernity in developing countries around the world. While North America has largely stopped building them or has shut down forever their little 1-HP motors, still they spin on in Kuala Lumpur, P’yongyang, and countless other places.

Despite being fairly easy to engineer and not really all that new, in the 1960s revolving buildings became symbols of progress. Often set atop communications towers, they were intended to help defray costs of tower construction and operation. Today, whether in towers or on hotel roofs (where they look like flying saucers that have landed), they continue to represent modernity in developing countries around the world. While North America has largely stopped building them or has shut down forever their little 1-HP motors, still they spin on in Kuala Lumpur, P’yongyang, and countless other places. For diners gazing from on high – whether upon the Pyramids, distant mountains, or, more often, streets clogged with traffic – revolving restaurants are pleasant. Who doesn’t enjoy the feeling of god-like detachment while sipping a martini and surveying a cityscape? Yet, on the whole revolving restaurants are geared more to “peak” dining occasions than to the consumption of haute cuisine. Their forgettable yet expensive food has tended not to win them steady local trade. Plus, tackiness such as found in Florida hotels with Polynesian restaurants twirling in the sky, or “Certificates of Orbit” such as once were given out at Butlin’s Revolving Restaurant in London’s post office tower (detail pictured), have branded them cheesy tourist traps in many people’s minds.

For diners gazing from on high – whether upon the Pyramids, distant mountains, or, more often, streets clogged with traffic – revolving restaurants are pleasant. Who doesn’t enjoy the feeling of god-like detachment while sipping a martini and surveying a cityscape? Yet, on the whole revolving restaurants are geared more to “peak” dining occasions than to the consumption of haute cuisine. Their forgettable yet expensive food has tended not to win them steady local trade. Plus, tackiness such as found in Florida hotels with Polynesian restaurants twirling in the sky, or “Certificates of Orbit” such as once were given out at Butlin’s Revolving Restaurant in London’s post office tower (detail pictured), have branded them cheesy tourist traps in many people’s minds. What could be more starkly different from the somber coffee shops of today with their earnest and wired denizens than the beatnik coffeehouses of the 1950s? Could Starbucks be anything but square to the beat generation?

What could be more starkly different from the somber coffee shops of today with their earnest and wired denizens than the beatnik coffeehouses of the 1950s? Could Starbucks be anything but square to the beat generation? Although the word beatnik came into usage around 1958 (inspired partly by Sputnik), the phenomenon of dropping out of the “rat race” to lead an existentialist, non-consumerist life was part of the aftermath of World War II akin to the “Lost Generation” after World War I. The first coffeehouses sprang up in Greenwich Village in the late 1940s, but the beats weren’t averse to hanging out in cafeterias either — their “Paris sidewalk restaurant thing of the time.” When coffeehouses began levying cover charges for performances, beatniks tended to drop out of them too.

Although the word beatnik came into usage around 1958 (inspired partly by Sputnik), the phenomenon of dropping out of the “rat race” to lead an existentialist, non-consumerist life was part of the aftermath of World War II akin to the “Lost Generation” after World War I. The first coffeehouses sprang up in Greenwich Village in the late 1940s, but the beats weren’t averse to hanging out in cafeterias either — their “Paris sidewalk restaurant thing of the time.” When coffeehouses began levying cover charges for performances, beatniks tended to drop out of them too. The heyday of the coffeehouse was the late 1950s into the early 1960s. Few did much cooking so they weren’t restaurants in the true sense, but many of them offered light food such as salami sandwiches (on exotic Italian bread) and cheesecake, along with “Espresso Romano,” the most expensive coffee ever seen in the U.S. up til then. Of course the charge for coffee was more a rent payment than anything else since patrons sat around for hours while consuming very little. Other then-unfamiliar food offerings included cannolis at La Gabbia (The Birdcage) in Queens, Swiss cuisine at Alberto’s in Westwood CA, Irish stew at Coffee ’n’ Confusion in D.C., les fromages at Café Oblique in Chicago, “Suffering Bastard Sundaes” at The Bizarre in Greenwich Village, and snacks such as chocolate-covered ants and caterpillars at the Green Spider in Denver.

The heyday of the coffeehouse was the late 1950s into the early 1960s. Few did much cooking so they weren’t restaurants in the true sense, but many of them offered light food such as salami sandwiches (on exotic Italian bread) and cheesecake, along with “Espresso Romano,” the most expensive coffee ever seen in the U.S. up til then. Of course the charge for coffee was more a rent payment than anything else since patrons sat around for hours while consuming very little. Other then-unfamiliar food offerings included cannolis at La Gabbia (The Birdcage) in Queens, Swiss cuisine at Alberto’s in Westwood CA, Irish stew at Coffee ’n’ Confusion in D.C., les fromages at Café Oblique in Chicago, “Suffering Bastard Sundaes” at The Bizarre in Greenwich Village, and snacks such as chocolate-covered ants and caterpillars at the Green Spider in Denver.

As the decade starts there are over 19,000 restaurant keepers, a number overshadowed by more than 71,000 saloon keepers, many of whom also serve food for free or at nominal cost. The institution of the “free lunch” has become so well entrenched that an industry develops to supply saloons with prepared food. As big cities grow, the number of restaurants swells, with most located in New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Massachusetts, and the Midwest where young single workers live in rooming houses that do not provide meals. Southern states and the thinly populated West, apart from California, have few restaurants.

As the decade starts there are over 19,000 restaurant keepers, a number overshadowed by more than 71,000 saloon keepers, many of whom also serve food for free or at nominal cost. The institution of the “free lunch” has become so well entrenched that an industry develops to supply saloons with prepared food. As big cities grow, the number of restaurants swells, with most located in New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Massachusetts, and the Midwest where young single workers live in rooming houses that do not provide meals. Southern states and the thinly populated West, apart from California, have few restaurants. Near the decade’s end, the “Gay 90s” commence and those who are able and so inclined pursue the good life, which increasingly includes going to restaurants for the evening. It is still considered somewhat disreputable to do this, so some people go out to dinner only when visiting another city.

Near the decade’s end, the “Gay 90s” commence and those who are able and so inclined pursue the good life, which increasingly includes going to restaurants for the evening. It is still considered somewhat disreputable to do this, so some people go out to dinner only when visiting another city. 1893 A drunken man fires five shots into

1893 A drunken man fires five shots into  1895 Competition from cafés and restaurants in Massachusetts has just about wiped out the old boarding houses where renters had all their meals supplied. One reason is that people prefer restaurants because they get to choose what and when they eat. – Boston’s Marston restaurant, established by sea captain Russell Marston in the 1840s, opens a women’s lunch room on Hanover Street.

1895 Competition from cafés and restaurants in Massachusetts has just about wiped out the old boarding houses where renters had all their meals supplied. One reason is that people prefer restaurants because they get to choose what and when they eat. – Boston’s Marston restaurant, established by sea captain Russell Marston in the 1840s, opens a women’s lunch room on Hanover Street. Where could you — once upon a time – enjoy European pastries, cinnamon toast, and ice cream soda while you hugged a teddy bear? Rumpelmayer’s, of course. A very popular rendezvous for pampered New York children after a visit to the zoo or the ballet. I suppose adults could hug the bears too, but Rumpelmayer’s sweetness – its confections, pink walls, and shelves of stuffed toys — might close in on you if you didn’t hold fast to some grown-up habits such as cigarettes and highballs.

Where could you — once upon a time – enjoy European pastries, cinnamon toast, and ice cream soda while you hugged a teddy bear? Rumpelmayer’s, of course. A very popular rendezvous for pampered New York children after a visit to the zoo or the ballet. I suppose adults could hug the bears too, but Rumpelmayer’s sweetness – its confections, pink walls, and shelves of stuffed toys — might close in on you if you didn’t hold fast to some grown-up habits such as cigarettes and highballs. Rumpelmayer’s tea and pastry café began its Manhattan life in 1930 in the new Hotel St. Moritz on the corner of Central Park South and Sixth Avenue. The hotel almost immediately went into foreclosure though it continued in business. Oh, happy day when Repeal commenced in December of 1933 and the St. Moritz announced, “In Rumpelmayer’s, as in the Grill, we will feature a number of bartenders with Perambulating Bars, for serving mixed drinks.” Bars might be everywhere, but Rumpelmayer’s other attractions were not. For decades it provided a jolly spot for children’s birthday parties, lunches, late Sunday breakfasts, and afternoon teas and hot chocolates. It closed around 1998.

Rumpelmayer’s tea and pastry café began its Manhattan life in 1930 in the new Hotel St. Moritz on the corner of Central Park South and Sixth Avenue. The hotel almost immediately went into foreclosure though it continued in business. Oh, happy day when Repeal commenced in December of 1933 and the St. Moritz announced, “In Rumpelmayer’s, as in the Grill, we will feature a number of bartenders with Perambulating Bars, for serving mixed drinks.” Bars might be everywhere, but Rumpelmayer’s other attractions were not. For decades it provided a jolly spot for children’s birthday parties, lunches, late Sunday breakfasts, and afternoon teas and hot chocolates. It closed around 1998. Always proud of its continental delicacies, New York’s Rumpelmayer’s was related (exactly how I’m not sure) to sister tea shops in London, Paris, and on the Riviera. The original Rumpelmayer’s was begun by an Austrian pastry cook in the German resort town of Baden-Baden in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. It then followed its Russian clientele to Cannes and Nice, then later to Mentone and Monte Carlo. In 1903 a shop was opened on Paris’s Rue de Rivoli (pictured, somewhat later) and in 1907 on St. James Street in London. Parisians, infected by Anglomania in the early 20th century, eagerly adopted the afternoon tea custom, in this case reputedly known as having a feeve o’clock-air at “Rumpie’s.” Though it was rated slightly less chic than the Ritz, it attracted mobs of fashionably dressed women who paraded their outfits up to the counter where, according to custom, they speared their chosen pastries with a fork.

Always proud of its continental delicacies, New York’s Rumpelmayer’s was related (exactly how I’m not sure) to sister tea shops in London, Paris, and on the Riviera. The original Rumpelmayer’s was begun by an Austrian pastry cook in the German resort town of Baden-Baden in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. It then followed its Russian clientele to Cannes and Nice, then later to Mentone and Monte Carlo. In 1903 a shop was opened on Paris’s Rue de Rivoli (pictured, somewhat later) and in 1907 on St. James Street in London. Parisians, infected by Anglomania in the early 20th century, eagerly adopted the afternoon tea custom, in this case reputedly known as having a feeve o’clock-air at “Rumpie’s.” Though it was rated slightly less chic than the Ritz, it attracted mobs of fashionably dressed women who paraded their outfits up to the counter where, according to custom, they speared their chosen pastries with a fork.

The restaurant business didn’t get much respect until it was sharply disconnected from drinking and put on a business-like footing in the Prohibition era of the

The restaurant business didn’t get much respect until it was sharply disconnected from drinking and put on a business-like footing in the Prohibition era of the

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.

It's great to hear from readers and I take time to answer queries. I can't always find what you are looking for, but I do appreciate getting thank yous no matter what the outcome.